A conversation about flash fiction with Grant Faulkner.

by Jayne Martin

Unlike novels, or even short stories, flash fiction is impatient. “Get on with it,” it says. Exposition is its death knell. It withholds, teases, and entices the reader to enter and then lingers like an all-too-real dream. Microfiction, a subgenre of flash, is normally described as under 300 words. Think of distilling a reduction sauce down to a single explosion of flavor.

With its roots firmly planted in the works of such writers as Raymond Carver, Grace Paley, Updike, Cheever, and Hemingway, flash fiction has been with us for decades. Consider Hemingway’s story collection “In Our Time,” first published in Paris in 1924. At 32 pages, it consists of 18 short works, some just a half page. But it wasn’t until 1986 that we saw the first published anthology of the form, “Sudden Fiction: American Short-Short Stories,” edited by Robert Shapard and James Thomas. Thomas would later be credited with coining the term “flash fiction,” which he described as stories between 250 and 750 words. In the ensuing years, microfiction has tightened the form even more as stories as short as 50 words have gained popularity.

Our own Bay Area is a hotbed of flash and microfiction talent. Prior to the recent health crisis and shelter-in-place orders, on any given night one could attend readings at beloved San Francisco bookstores like the Bindery, Green Apple, and Alley Cat, and that’s without even venturing out to the East Bay or Marin, where the flash scene is just as vibrant.

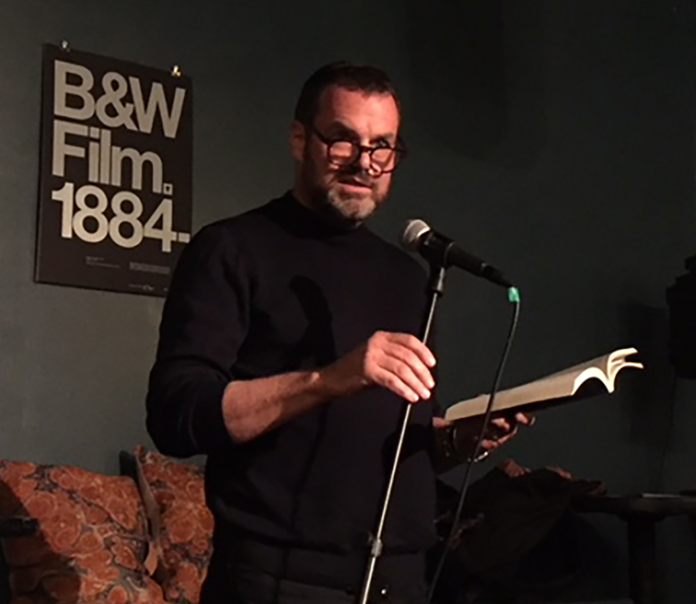

I first met local author Grant Faulkner in mid-2018 for the book launch of “Nothing Short Of: Selected Tales from 100 Word Story,” held at the Bindery on Haight Street. Culled from stories from the online journal of the same name founded by Faulkner and Lynn Mundell in 2011, the anthology celebrates the literary inventiveness of microfiction. An enthusiastic crowd of writers and fans of the genre gathered in the bookstore’s back room, congregating around the well-stocked wine bar. Rows of chairs faced a makeshift stage where a single microphone on a stand awaited. Most of us had only met online prior to this evening and we were tentative with each other at first. I was both honored to have my story “The Wedding Night” included in the collection and nervous about reading it aloud in front of local masters of the form like Robert Scotellaro, Jacqueline Doyle, Jane Ciabattari, and Jon Sindell. Topping six feet tall, with a smile that could span the Golden Gate, Faulkner circulated through the group, graciously introducing himself to us and us to each other. By the end of the evening, we were all exchanging our books for signatures like giddy high school seniors on yearbook day. I didn’t know then that only a year later, Faulkner would generously provide a blurb for the back cover of my own microfiction collection, “Tender Cuts,” from Vine Leaves Press.

A graduate of San Francisco State with an M.F.A. in creative writing, Faulkner is also the executive director of National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo); author of “Pep Talks for Writers: 52 Insights and Actions to Boost Your Creative Mojo” and his own collection of micro, “Fissures”; and a member of the Oakland Book Festival’s Literary Council. Talk about street cred.

I’d hoped to catch up with him for a chat about the genre over a bowl of shakshuka at Manny’s or a cappuccino at Caffè Trieste, but instead we found ourselves at “Café” FaceTime, social distancing and ordering in.

I wondered out loud how a boy from Oskaloosa, Iowa, ended up in our City by the Bay. Turns out, like many drawn to SF’s artistic heritage, Faulkner and his writing chops arrived here in the late ’90s, when he was in his early 20s, and just never left.

“I had no plans to stay here for more than a year or so, but I found my people, my community, my home,” he explained. “San Francisco was a wonderful place to be a writer then. The rents were affordable, especially compared to now, and the Mission was an emerging scene of cafés, bookstores, and bars. It was one of those great moments of creativity when so many people were doing such cool and daring things in a concentrated, small part of the city. I got my M.F.A. hoping it would qualify me to teach.”

Now, a couple of decades later, Faulkner is living in Berkeley, writing, teaching, and advocating for flash and microfiction.

“Flash fiction has simmered in the literary background for decades only to take off like a brush fire fairly recently. Any thoughts on that?” I asked.

“We live in an increasingly fragmentary world, where experiences and memories seem more fleeting than ever, so I think flash speaks to our reality and can represent it in a way that longer forms sometimes can’t. Also, in this world of emails, texts, and social media, people’s reading styles have changed. We scan and read in nuggets. That said, most flash fiction shouldn’t be read in such a breezy fashion because shorter stories often border on prose poetry and can be just as complicated as a longer work.”

I dunked my dim sum in the tiny plastic container of soy sauce and thought about that comparison. Like poetry, one of flash’s unique qualities is its openness to interpretation. Its purposeful gaps.

“Toni Morrison said, ‘It is what you don’t write that frequently gives what you do write its power.’ Do you agree?” I asked.

“It’s one of the things I enjoy most about writing and reading flash, that omission. It’s as important as the text on the page. In ‘The Pleasure of the Text,’ Roland Barthes asks, ‘Is not the most erotic portion of the body where the garment gapes?’ Flash, and especially micro, lure the reader forward by escalating hints and implications. The reader needs to pause, reflect, and fill in those spaces—to be a co-creator, essentially. It’s their story as much as it is the writer’s.”

“Yes,” I said. “I love it when a reader tells me about something they got from one of my stories that I didn’t consciously intend. Like when you’re a kid seeing different shapes in clouds with your friend. ‘Look! There’s a shark!’ And your friend says, ‘No. That’s a wolf!’ Interpretation. It’s as unique as our DNA.”

As dogs (mine) and kids (his) began to vie for our attention off-screen, we decided to wrap things up with, appropriately, endings. Faulkner looked to a metaphor.

“Because of the compressed nature of flash fiction, endings are even more important. In such a short form you’ve got to nail the ending like a gymnast. If you waver, tip, or fall, you’ll ruin everything you’ve previously achieved. The last sentence matters far more than in a novel or even a conventional short story.”

My take was slightly different.

“You have to know when to leave the party,” I offered. “The writer needs to slip out of the story while the reader is still having a good time. While their imagination is still engaged, so that even though the writer may have come to the end, the reader lingers, hoping for another glass of wine.”

We agreed that the hallmark of well-written flash is emotional resonance. It must leave the reader feeling something. Otherwise, it risks just being clever, and when writing flash and micro, clever is the booby prize. ♦

Jayne Martin is a native San Franciscan whose family roots in the City can be traced back to the early 1900s. The booking manager for 245 Hyde Street studios back when it was Wally Heider Recording, she recalls the Grateful Dead always having the best hash. After a couple of decades writing movies for television, she turned her writing chops to flash and microfiction, resulting in the publication of “Tender Cuts” from Vine Leaves Press, a collection of 38 stories all under 300 words.