A quest to discover the source of a mysterious sound at Lands End dives deep into our fraught relationship with the forest.

San Francisco’s hottest day on record was Friday, September 1, 2017.

The most bewildering thing about that day—in a city where one must always pack a parka when going out—was not the flood of people spilling out of their homes to go sunbathing at the beach (giving the impression that the population had suddenly doubled), nor was it the ominous orange haze that had settled over the city as a result of wildfires to the north. It wasn’t the water at China Beach, either, which was still unbelievably, achingly cold, or the mesmerizing show put on by a school of dolphins right off the shore.

Instead, the most bewildering thing that day was an unexpected sound coming from the forest canopy.

I first noticed it walking through Sea Cliff toward China Beach, out with my husband on a late-afternoon stroll prompted by our inability to work a minute longer in offices that lacked air-conditioning. As we made our way to the beach, it seemed like everyone else in San Francisco had also decided to take the day off, basking in the novelty of that rare late-summer heat.

Somewhere along El Camino Del Mar, in the heavy air, we heard a peculiar noise: a crisp snap followed by a soft rustle. And another, about a minute later.

They seemed to follow us as we approached the wooded edge of Sea Cliff—tiny articulated explosions in surround sound above our heads. I sidestepped instinctively, anticipating a plummeting branch that never fell. We angled our heads skyward, looking for a source, and found none.

We ended up in Lands End, where the hustle and bustle quieted down and the persistent popping intensified. It was as if the trees were coming alive: stretching their limbs, cracking their knuckles. Perplexed, fellow San Franciscans turned their heads and, shading their eyes, squinted into the hazy golden streaks of sunlight. I made eye contact with a stranger or two, and we exchanged smiles of mild surprise, bonded by the extraordinary events of the day, for which we had no explanation.

. . .

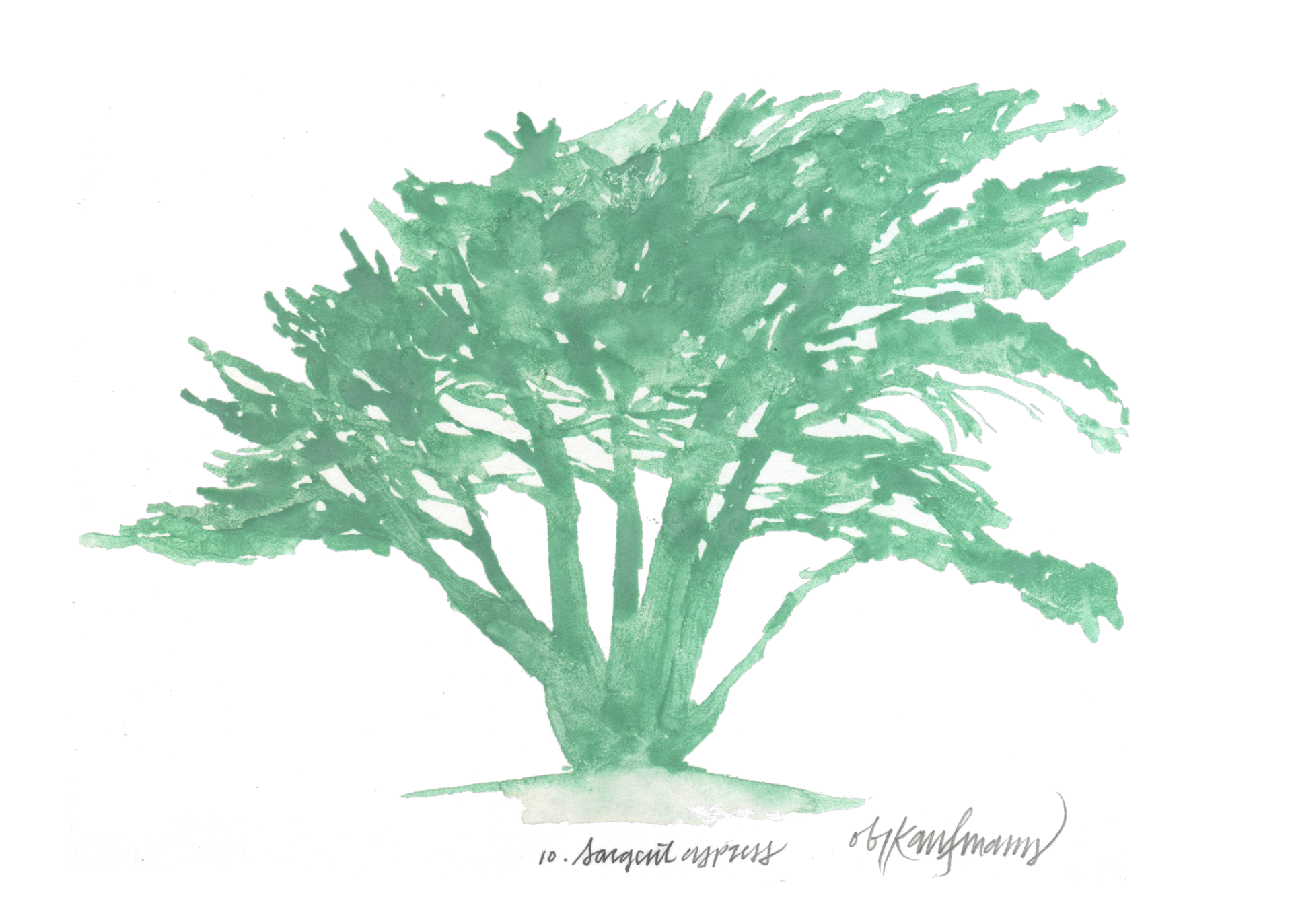

It wasn’t until several years later that I stumbled upon a clue in Obi Kaufmann’s illustrated guide to California ecology, The California Field Atlas, which I’d picked up at my local bookstore. In a chapter exploring the relationship between fire and forest, Kaufmann wrote, “The closed-cone pine forests of the coast won’t open their tightly bound seed cones until temperatures soar, as in the presence of direct flame.” It’s an evolutionary adaptation known as serotiny: the delayed flowering of some plants or trees until triggered by certain environmental conditions, such as wildfires.

“Every single native tree species in California has a strategy to deal with extreme heat,” Kaufmann told me when I reached him by phone at his East Bay studio in September of 2021. “They do this by either being adapted to heat and fire or by being dependent on it, as in the case of serotinous cone–bearing trees.”

These trees, Kaufmann explained, have evolved over millennia to hold onto their seeds, protecting them in hard cones from “all kinds of exotic stress,” including insects, mold, and dampness, and only releasing them in optimal conditions. When a natural wildfire occurs, the resin that coats the outer layer of the cones melts, causing them to open not gradually but in a sudden burst: the source of the popping noise that sweltering September day. Then, as the fire scorches the ground at the base of the trees, it clears out the underbrush and leaves behind a bed of soil rich with phosphorus, nitrogen, and other natural fertilizers. In the heat of the fire, the trees release their seeds, giving them the best possible chance to pollinate in the wind and reach fertile soil before the rains of November.

San Francisco wasn’t on fire that blistering hot day in 2017, but it felt like it. And the serotinous trees, confused, began setting off their reproduction mechanism in the branches above our heads.

For all the time I’d spent looking up in wonder on that record-breaking day, I hadn’t given much thought to the individual species populating San Francisco’s urban forest. But Kaufmann’s explanation of the science of serotiny had piqued my curiosity. With the help of hyperlocal guides The Trees of San Francisco by Mike Sullivan and The Trees of Golden Gate Park and San Francisco by Elizabeth McClintock, I was able to identify two evident sources of the heat-induced popping: Monterey pine and Monterey cypress. Both species are serotinous conifers, and both exist in abundance at Lands End. To my surprise, I learned from Sullivan and McClintock that these trees are not native but rather two examples of the many thousands of transplants—human and nonhuman—that inhabit our fair city. And as it turns out, their histories and futures remain inextricably linked to our own.

. . .

Later that September, I arranged to meet Blake Troxel, forester at the Presidio Trust, for a walk through one of the park’s oldest forest stands. With its 1,500 acres of winding trails and recreational space, the Presidio contains one of the largest concentrations of Monterey pine and Monterey cypress in the city. I’d hoped that Troxel, as caretaker for this corner of our urban forest, could help me understand how trees adapted for semiregular wildfires had come to thrive in the carefully regulated parks of a populous city.

The weather on the day of my visit was cool, with the sun straining through a layer of fog. Following the coordinates Troxel had sent me, I found myself just south of the intersection of Park and Lincoln Boulevards, among a convergence of old and new tree growth. Although it’s not labeled on any maps, the stand (one of four historic stands in the park) is Troxel’s favorite part of the Presidio. “This was one of the first places I came when I started working here,” he told me. The statement held a degree of sentiment; this was his last week on the job after four years. The gently sloping hillside to our left was filled with young evergreen trees and native plants he and his team had planted and maintained over the past four years: the next generation of the park’s forest.

The prevailing generation of trees, some up to 150 years old, were planted by the city’s first foresters. “The trees that they planted the most were those that did best in our foggy summers and sandy soils,” Troxel explained. As I had learned from my guidebooks, Monterey cypress and Monterey pine, endemic to Monterey County and the central California coast, were two such species.

As we spoke, I followed Troxel along a portion of the Presidio’s scenic Park Trail, which meanders north-south between the park’s 14th Avenue Gate and Crissy Field. For the entirety of the trail, there is no view deprived of Monterey cypress: they stand proudly over former army buildings and the National Cemetery, with dramatic windswept silhouettes and mossy, coral-shaped foliage. Monterey pines, never far away, decorate the park in similar grandeur, identifiable by their bundled needles and pointed pine cones reminiscent of seashells. Together, the two conifers fill the hillsides along San Francisco’s boulevards, stand guard along our coasts, and provide the canopy to our parks. It’s no wonder the sounds of serotiny had been so ubiquitous in 2017: the two trees, along with blue gum eucalyptus, make up 28 percent of the city’s entire tree population, according to a US Forest Service analysis from 2004. This is a fact that’s even more remarkable considering that just 150 years ago, they didn’t exist at all in San Francisco.

In stark contrast to today’s verdant hillsides, the mid-nineteenth-century landscape of the Presidio “was all scrub and dune,” Troxel told me, as was the entire western half of San Francisco. Trees in particular “were never a prominent feature on the northern tip of the narrow, windswept San Francisco Peninsula,” botanist McClintock writes in The Trees of Golden Gate Park and San Francisco. Frederick Law Olmstead, a prominent landscape architect of the nineteenth century, put it more bluntly: “There is not a full-grown tree of beautiful proportions near San Francisco.” (Local natural historians would be quick to point out Olmstead’s omission of the mature native live oak and California buckeye that dotted the coasts and hillsides at the time.)

It wasn’t until 1870—when city officials appointed William Hammond Hall to build a sprawling public park on the western side of the city—that much of the current tree population was introduced. Hall, a civil engineer with limited landscaping experience, rose to meet the challenge. After extensive research on the soil, water, and native plants of the area, he chose three hardy, fast-growing species as the first new inhabitants of that sandy soil: Eucalyptus globulus (blue gum eucalyptus, native to the southern coast of Australia), Cupressus macrocarpa (Monterey cypress), and Pinus radiata (Monterey pine). Because they were fast-growing and wind-tolerant, Hall knew the trees would provide much-needed shelter for more delicate species he planned to eventually plant throughout the thousand acres that would become Golden Gate Park. He set about planting the young trees in dense groups, allowing them to support each other in the winds, and later thinned them out as they grew. At the same time, he used strategic soil management techniques to tame the shifting sand dunes on the western edge of the park, transforming, in his own words, “wandering hillocks into fixed and productive features of topography.” Within a decade, San Francisco had sprouted its own version of Central Park, and William Hammond Hall had established a horticultural blueprint that would be used across the city’s recreational spaces for the next thirty years.

In the Presidio, Major William Jones of the US Army Corps of Engineers developed his “Plan for the Cultivation of Trees Upon the Presidio Reservation” in 1883, influenced by Hall’s experimentation thirteen years prior. Jones’s plan included planting three hundred acres of army grounds with the same three tree species, bringing in seventy-five thousand saplings to construct a forest atop the area’s serpentine grasslands.

Elsewhere among the city’s budding recreational spaces, landscape architects took note. Adolph Sutro, at the time a successful entrepreneur and real estate investor, planted an abundance of eucalyptus, cypress, and pine around the areas now known as Lands End, Mount Sutro, and Mount Davidson. Famed horticulturist John McLaren took over as Golden Gate Park superintendent in 1887, using Hall’s planting method (“plant thick, thin quick”) to diversify and develop the park over the next fifty-six years. By the turn of the century, the natural skyline of San Francisco had drastically changed from rolling sand dunes and grassland to a densely packed metropolis of trees.

. . .

There are some pockets of the West Coast that, when viewed at a certain angle in quiet hours of the day, offer a glimpse into the California of ages past. Pacific Grove, on the cool misty peninsula at the northwestern tip of Monterey County, is one such place. My childhood was peppered with trips to this little coastal town, where my family would house-sit for a friend who owned an old Victorian. There, traipsing along the trails of the nearby Del Monte Forest in my tiny Reeboks, I’d unknowingly walked among the only native stands of Pinus radiata and Cupressus macrocarpa in the world.

The Del Monte Forest, a census-designated place that includes a smattering of golf courses and the seaside town of Pebble Beach, has been home to Monterey pine and Monterey cypress for thousands of years. Here they can live up to 150 and 300 years respectively (the famous Lone Cypress, standing on a granite outcropping in Pebble Beach, is thought to be around 250 years old). As the trees age, it’s not uncommon for the resin in their cones to dry out, causing the closed cones to creak open, exposing seeds that eventually make their way to the ground by way of wind and gravity. In the event of a fire, however, this reproductive process gets fast-tracked. And despite its damp climate, the Central California coast has historically seen more fire than one might expect.

The California Fire Science Consortium, a network of fire scientists and experts, has conducted a wealth of research on fire patterns across California’s widely varying regions. “We know the coastal environments are not as fire-prone as areas like the dry Sierra Nevadas,” program coordinator Stacey Sargent Frederick told me, “but we can see regular fire occurrences over time [in coastal regions] from scientific methods like measuring ash layers, combined with Native American oral histories.”

Long before European colonists set foot on California soil, Indigenous peoples were using fire as a tool. “Analogous to fire-dependent species, many indigenous peoples and Tribal communities are fire-dependent cultures,” wrote Frank Kanawha Lake in a 2021 article titled “Indigenous Fire Stewardship: Federal/Tribal Partnerships for Wildland Fire Research and Management.” Lake, a research ecologist for the Forest Service, is a descendant of the Yurok and Karuk people, two communities based in the Klamath River region of northwestern California. With deeply ingrained knowledge of the drought and wind patterns along the Klamath River, the Yurok and Karuk knew when igniting a controlled fire would yield the best conditions for hunting, planting crops, and gathering natural resources.

Practiced at regular intervals, this burning kept brush and buildup at bay, cleansing the ground and giving trees and plants better conditions for regeneration. Fire, Lake wrote, was a type of medicine: “Not enough fire can make the land and people sick.” Similarly, the Ohlone people burned concentrated tracts of land in precolonial San Francisco, promoting the growth of native grasses for basket weaving and replenishing oak trees in the area, which provided a bountiful acorn crop for humans and animals alike.

However, as colonizers claimed Indigenous land as their own along the California coast, long-held Indigenous fire traditions were swiftly abolished in an effort to protect the state’s valuable timber industry, while Native American communities perished from disease. Obi Kaufmann described this as a dangerous trifecta of white settlers’ commodification of the forest (which included dense replanting of forests for timber), a sweeping federal fire suppression policy, and colonial violence toward Indigenous relationships to fire. Together, these factors set in motion decades of dangerous conditions that have contributed to today’s era of megafires.

“The belief—the cutting-edge science at the time—was that if you suppress fire enough, fire will just go away,” Kaufmann said. This turned out to be dangerously false, as Frederick illustrated to me in further detail. “When we took fire out of our ecosystems,” she said, “it led to an accumulation of vegetation and brush. Now, when a fire comes through, especially when conditions are very dry, we see much different fire behavior than if the area had been burning under historical conditions.” In the seven years Frederick has worked with the California Fire Science Consortium, the number of acres burned each year has risen exponentially. Recent changes in climate mean that California is much hotter and drier now than it was one hundred years ago, a fourth threat added to the trifecta.

Frederick outlined two main mentalities that trees exhibit in fire. “Certain trees know that when the fire comes through, they’re probably going to die, so they’ll try to give their seedlings the best chance possible.” Eucalyptus falls into this category: its leaves and bark are highly flammable, but the burning of its bark exposes protected buds that sprout new life. “Other trees, if they’re big enough and have thick enough bark, can survive along with their propagations,” Frederick said. Along with the massive sequoias and redwoods that have grown for centuries in California, Monterey cypress and Monterey pine have historically fallen into the second category, although an intense-enough fire can still reach the crown of the tree, killing it. The problem is, each year brings more intense fires than the last, increasing this risk for trees that could previously withstand fire in their native habitats.

Curbing these devastating megafires requires a combination of intervention efforts, Lake and Frederick both emphasized. By reincorporating native land management practices and actively restoring the balance of forest ecosystems, we can begin the long process of undoing a century’s worth of harm.

. . .

In our own metropolitan backyard, where wildfires aren’t generally a threat, similar unintended effects of past mistakes in forest management remain visible. Along Park Boulevard in the Presidio, a dense thicket of Monterey cypress towers upwards of sixty feet, old-timers from the park’s first afforestation efforts in the 1880s. “If you look, the trees here aren’t very healthy,” said Troxel during our conversation at the historic stand. He gestured to the trees’ crowns, the clusters of foliage gathered atop towering bare trunks. In a healthy tree, he explained, the ratio of flourishing branches to trunk is much higher. But these Monterey cypress were planted so close together they couldn’t afford the extra greenery. “They’re all competing for light at the same time,” Troxel said. “They didn’t have a chance to grow out, they only grew straight up.”

The sloping hillside to the east used to look just like this. But in the last decade, Troxel and his team have cleared out the old trees to make way for a new generation that can grow stronger and healthier. It’s their way of replicating the kind of natural fire event these trees have evolved with, a method of maintaining the Presidio’s man-made forest. “When we come in, we kick start the restoration cycle,” Troxel explained. “We have to clear out everything and start over from scratch.”

The youngest trees in the reforestation area are about a year old, most of them about the height of my waist. Plantings had occurred in batches, with the age of the trees gradually increasing to about five years old as one walks up the Park Trail. “Give it ten years,” Troxel said, “and these trees will be twenty to thirty feet tall.”

This reforestation effort in the Presidio is just one of many ways humans have guided the growth and preservation of San Francisco’s green spaces. And, as replanting projects continue across the city’s parks, the guidelines set forth by William Hammond Hall and his contemporaries in the 1880s have persisted. Troxel referenced the 2009 “Historic Forest Character Study,” which documents the makeup of the Presidio’s urban forest and includes detailed guidelines on how to maintain and rehabilitate the area. “This area in particular is one of our key historic stands in the park,” he said. “So the species composition is required to be similar to what was here before.”

The vast majority of young trees in the reforestation area, then, are Monterey cypress. They are accompanied by an undergrowth of native plants like toyon and lupine, in an effort by the Presidio’s native plant restoration team to reintroduce some of the plants that were wiped out in the nineteenth century. The toyon and lupine can help restore balance by keeping down the population of invasive species like ivy and blackberry, which have grown unchecked in other areas like Mount Sutro and Mount Davidson. “We’re finding that [reintroducing more native plants] has a lot of benefits,” Troxel said. “Not only for the trees, but for the birds, insects, and other small mammals in the habitat.”

A few Monterey pine trees are sprinkled throughout the new growth, but in much fewer numbers. This is largely due to natural forces out of our control: over the past thirty years, a disease called pitch canker has ravaged California’s pine populations, infecting branches and trunks with a telltale oozing resin, or pitch. Even among the young pine trees Troxel’s team has planted, swatches of brown needles stick out like sore thumbs among the greenery, evidence of the disease’s prevalence even in a closely monitored environment.

The third hardy tree planted in those early days, blue gum eucalyptus, has seen a gradual decline in plantings as well, for reasons more closely tied to climate change. These eucalyptus trees are dangerously fire-prone, Troxel explained, an increasing risk in areas with rising temperatures. They are also a very thirsty species: not only do they require more water than most other trees in the parks, they can also deprive other species of water, preventing a healthy understory from growing. As California experiences higher temperatures and more intense droughts, parched eucalyptus trees may pose more of a threat to certain landscapes than they did 150 years ago.

At this point during my visit, Troxel echoed the inevitable truth that had surfaced in each of my conversations surrounding California’s forest ecology: “Everyone will have to make changes in the next ten or twenty years, no matter where you are.” While the state struggles to implement plans for wildfire prevention and reintroduce native land management techniques, horticulturists and arborists at the local level must determine which species can responsibly be planted in an urban or suburban area based on a changing climate. And although a certain degree of irreversible harm has already been done, I’m reminded of a point made by Obi Kaufmann. As Californians, he said, “we have a chance to leave our natural world in better shape at the end of the twenty-first century than we did at the end of the twentieth century. It’s as much of an opportunity as it is a challenge.”

As Troxel and I wrapped up our conversation, one tiny pine sprout near the trail caught my eye. It was no more than six inches tall, surrounded by a sprinkling of wood chips. “That was most likely a volunteer,” Troxel said, as I fawned over the miniature sprig of pine needles. “Volunteer” is the name for a tree that grows from seed without human intervention. When possible, Troxel’s team promotes natural propagation, encouraging the forest to self-regenerate as much as possible. These volunteers, after all, have already demonstrated their tenacity by surviving against the odds. Before leaving, I snapped a picture of the Monterey pine volunteer, a natural wonder in a man-made forest.

. . .

On a recent walk through Lands End, my attention was drawn to the San Francisco trees I’ve grown to know well. The evening air was thick with fog, and listening closely, I could hear the plunks of droplets falling from leaves. It was a stark contrast to that 106-degree day in September 2017, when the serotinous cones first caught my attention, and I’ve yet to hear them pop in such concentrated splendor again. But even in silence, I noticed them now. I noted the difference in the shapes of each tree’s cones: curved and asymmetrical on the Monterey pine, small and round on the Monterey cypress.

Pausing alongside the paved road that cuts through the golf course, I saw a cluster of young Monterey pine saplings at the base of a mature tree. Most were about three or four feet tall, just like the patches of new growth Troxel had shown me in the Presidio. Could these saplings have taken root that day in 2017? Recent conversations indicate this is possible, and I’d like to believe it’s true.

There in the clearing by the golf course, I thought about how the majority of these young trees, if they survive into adulthood, should lead a perfectly normal life here on the foggy peninsula, their cones culminating in a quiet blossoming and an eventual tumble to the earth. But all it takes is one record-breaking heat wave—the likes of which are becoming more frequent each year—for them to burst into existence all at once, demanding our attention as their seeds float to the soil below, hoping for a grand rebirth. ♦

Nikki Collister hails from Southern California but considers herself a San Franciscan at heart. She graduated with a degree in ethnomusicology and works as a product manager in the travel industry. In her spare time, she enjoys blogging about classic rock and running an Instagram account for her cat, Special Agent Dale Cooper.

Robin Galante is an artist obsessed with San Francisco. She grew up on the Peninsula and narrowly escaped the grind of Silicon Valley, in favor of a fun, glamorous, and at times nail-biting career pursuing her artistic ambitions. She lives in the Outer Richmond with her husband and two troublesome cats.