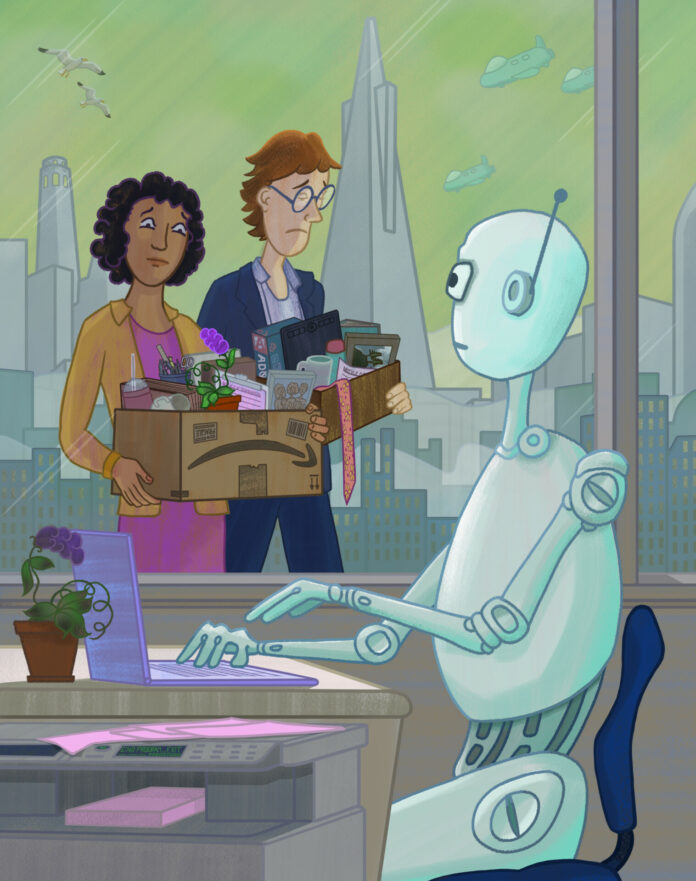

A journalist contends with the growing array of AI tools that are intended to augment—or replace—him.

A computer program helped write the headline above.

As a neurotic journalist, I’m amazed and terrified by this. The competing promises of AI—to both simplify my work and erase the need for it—are a little too imminent for comfort.

I’m struggling with how rational my concerns are, but what I do know is that fears are not always rational. My brain has been somersaulting through the ramifications of a technology that even scientists don’t fully understand.

The promise of a tool that can automate tasks that took me years to learn, develop, and sharpen feels like a missile headed directly for my career.

I’m asking myself the kinds of heady philosophical questions that I would generally scoff at: What is the true value of my craft? What do we lose when we cede our creative life to a machine? Who am I in a world where anyone can write a piece like this with just a few simple prompts?

Then other times, I think maybe I’ll just take up dog walking.

No one knows, ultimately, how generative AI—technology that can produce text, images, and other media—will change the job market and the nature of creative work. Policymakers appear to be taking an early and active role in trying to regulate the technology and head off likely massive labor and social shifts. Yet projections from some economic analysts are chilling.

A March report from Goldman Sachs found that AI could eliminate or partially automate some 300 million full-time jobs, with administrative workers and lawyers listed as two fields expected to be most affected.

That prediction was paired with optimism that labor productivity would rise in line with technological revolutions like the personal computer and reassurance that industries are “more likely to be complemented rather than substituted by AI.” The report also raised the potential for the creation of jobs and occupations that never existed before.

San Francisco leaders are banking on that promise as they prepare to launch the city into its next boom. Mayor London Breed has declared San Francisco “the AI capital of the world,” and boosters have hung their hopes on AI companies filling empty offices and kickstarting an economic recovery.

But the revolutionary tools have drastically cut work opportunities for people like Emily Hanley. The Los Angeles–based writer published a column laying out how her copywriting gigs gradually, then suddenly, dried up because, she inferred, clients were turning to ChatGPT for a cheaper alternative.

A desperate job search garnered an interview with a company that in a bit of brutal irony was offering a six-month contract to train its own internal AI on copywriting tasks. She didn’t end up getting the job and now works passing out samples at grocery stores.

AI is also a central antagonist in the strikes called by the Writers Guild of America and SAG-AFTRA. Both organizations have positioned algorithmically generated content as a pervasive threat to the idea of creative work.

Ultimately, the growing divide appears to be between those who feel they can take advantage of AI and those who will be swept away in its reshaping of the larger economy. What side of that split will I find myself on?

. . .

Using ChatGPT for the first time is a miraculous experience, but one that gradually leads to a slightly sickly feeling in the stomach, like gorging yourself on too much Mitchell’s Ice Cream.

Cracking open the technology and peering under the hood is an important step in moving from suspicion to understanding. That’s part of what inspired San Francisco journalist and writer Laird Harrison to dive deep into how to use the technology.

Harrison now teaches a class through the San Francisco–based Writers Grotto titled “Use AI to Improve Your Writing.” His course is meant to help students effectively utilize technology as a tool and avoid common pitfalls. Harrison’s use of AI is driven by a feeling that the technology is transformative, whether he likes it or not.

“If I had the choice and I could roll back the clock and not have AI invented, I probably would,” Harrison said. “But I can’t, so I’m trying to figure out how to make use of it and how to help other people make use of it.”

In some of his early experiments with ChatGPT, the brand-name generative AI tool that can generate text, he asked the platform to take a medical journal article and turn it into a news story. The technology did a great job in reformatting the piece and writing it in an accessible style but also tacked on “facts” that were simply untrue.

“It’s almost the opposite of what we’re used to with computers, where we expect computers to be really, really good at facts and logic and precision but not able to understand ordinary human conversation,” Harrison said. “Here it’s just flipped.”

Generative AI platforms like ChatGPT lack an independent model for the world, meaning they are prone to mistakes. The technology is excellent at bullshitting and sounding extremely confident while doing so.

These tools work on a very complex pattern-recognition system—in effect, a highly advanced form of autocomplete. Based on their training data, generative AI platforms predict and generate the most statistically likely word to come next.

However, there are ways to trip it up.

One common experiment is asking a generative AI platform to multiply two large numbers. More often than not, the technology will get the answer wrong. That’s because the model’s technology doesn’t really understand math but instead generates an answer based off similar multiplication problems gleaned from its massive volume of training data.

Calculations require more precision than say, writing a sonnet in the style of William Shakespeare.

For his students, Harrison recommends using the models as a way to spark ideation or chip away at writer’s block. The models are great at helping to come up with baseline scenarios, character details, metaphors, elevator pitches, and titles. Harrison recently used the model to help generate long-winded “business speak” for character dialogue.

There are also more workaday uses, like organizing outlines, condensing language, and rewriting content as social media posts or press releases.

One of the unanswered questions Harrison is weighing is how critical it is to teach basic skills like grammar and sentence structure in a world of AI. Are they tantamount to the now-archaic requirements for penmanship and cursive writing that were superseded by computer word processing?

“I want the next generation of journalists to learn how to do all the things I had to learn, but I also think I have to teach them how to use tools that avoid doing some of the things I had to learn,” Harrison said.

Vipul Vyas is an adjunct professor at the University of San Francisco and an executive at San Francisco startup Persado, which is using generative AI to personalize marketing messages for consumers.

“White-collar labor is going to go from producing to directing,” Vyas said. “It’s the same way that a backhoe operator has gone from directing a machine versus digging via brute force.”

Vyas requires the use of generative AI models by his students because of that belief. He describes the core driver of this technology as “drudgery removal”: in essence, creating a situation where a mocking blank sheet of paper or an unfilled report will never exist again.

He believes white-collar job destruction or at least reduction will be in the fields that rely heavily on pattern recognition and repetitive tasks.

So will copywriters still exist in five or ten years? Not in the same form, Vyas said. It’s a matter of scale: while a human has a limited amount of lived experience, a large language model is an aggregation of millions.

“If you’re trying to sell something as a copywriter, you may just want what is most effective,” Vyas said. “If you’re trying to express something novel, it’s a different story. A Best Buy in Sunnyvale is not the height of architecture, it’s the height of efficiency and efficacy.”

. . .

One person who does not have a problem being a public evangelist for the use of AI is Michael Nuñez, the editorial director of VentureBeat, a tech-focused publication headquartered in San Francisco.

“By the end of the year, I think that generative AI will touch every part of the process of news, from ideation to headline generation to story editing,” Nuñez said onstage at a panel hosted by the San Francisco Press Club.

Nuñez said he uses AI-enabled chatbots to research and summarize topics, brainstorm new ideas, formulate headlines, copyedit articles, and rewrite clunky sections. In one case, Nuñez used ChatGPT to turn his notes from a boozy tech event into a coherent article that he edited and published the next day.

Further, he added that he didn’t think readers particularly cared about unattributed bits of language written by a chatbot and inserted into a story, given the content is independently verified. The statement garnered a fair amount of criticism mostly centered around transparency to readers, but Nuñez is not waffling.

“Everyone was really meager and afraid of the technology,” Nuñez said of his experience in the panel. “Everyone seemed to be talking about why not to use it.”

Specifically, the panel raised issues including AI “hallucination” of false information and the new technology overriding foundational journalism ethics and education.

Many journalists have reflexive skepticism of disruptive new developments in the tech sector, which have historically rapidly created new centers of powers and wealth, alongside unforeseen collateral damage.

Nuñez said his own initial skepticism started to turn after stress testing the platforms and learning that essentially the entire history of human writing was incorporated into the model.

“It included every biblical text, every Wikipedia page, and the work of the Esquire and New York Magazine writers I read growing up,” Nuñez said. “Just knowing that all my favorite writers were included in the model helped unlock for me what it was capable of.”

But that voracious ingestion of content has become a source of legal conflict. Numerous groups have sued Google and ChatGPT’s parent company, OpenAI, accusing the companies of stealing copyrighted material and personal private information without consent.

Criticism of AI in media and journalism ranges from platforms publishing false information to dislocation in a profession already cut to the bone with layoffs and shrinking budgets.

The genuine idea by AI proponents is nearly always that the technology will free up time for “higher-value tasks.” Not having to read through and annotate a 100-page report or write up rote copy about a new product release, for example, means more time for “the human element of journalism,” Nuñez said.

In his conception, this means journalists will be encouraged—or forced—to do more original reporting, hunting down sources, conducting interviews, and experiencing or observing things firsthand. Analysis and personal perspective will become more valuable differentiators as straight news becomes commodified.

I struggle a bit with this idea. Reading the 100-page report is not necessarily a low-level task; it builds a keen eye for detail and newsworthiness. In my own career, there have been many times when a footnote or throwaway detail in a voluminous study has become its own lead. It’s an open question, however, whether that argument will be increasingly archaic.

“It’s a little scary to know that people who have spent their entire lives training to become an expert in their field can be outmoded in the snap of a finger,” Nuñez said. “But I think it forces you to drill down—what is really your expertise?”

Nuñez uses the metaphor of a tsunami to refer to AI, a technology that will wash over an array of industries and leave only the strongest and most prepared entities standing. His hope is to catch the wave and ride it all the way to the end.

. . .

There are some who hold out hope that AI could help those with creative ideas to leapfrog the frustration, training, credentialism, and years of low-paid work that are hurdles to taking concepts to fruition. Would greater use of the technology build a more even playing field, where any idea that can be conceived can be produced?

That’s the inspiration for Pickaxe, a startup cofounded by Mike Gioia to help turn descriptions of plots and characters into scripted scenes using AI. Gioia’s idea is to democratize access to the entertainment industry by lowering the barrier for entry to anyone with a good idea and sense for story.

More recently, he has found himself in a bit of an awkward position as an AI optimist in an entertainment industry in full revolt against the technology.

“The life story of a lot of these filmmakers is being told they don’t have enough money or resources to make what they want to make,” said Gioia, a Stanford University graduate who has worked in independent film and television writing rooms. “I very much see it as a way for independent filmmakers to go farther.”

He drew a distinction between writers and actors who are seeing their fields potentially disrupted for the first time and postproduction workers like those working in virtual effects. These visual effects artists have continually seen novel software and technology become industry standard, meaning flexibility and willingness to adapt to new tools have been critical to remaining successful.

“Their work has been disrupted every two or three years, so they’re used to it,” Gioia said. “Postproduction people see it as a work multiplier, but writers definitely feel like it’s a work replacer.”

Gioia is skeptical that AI will completely replace writers; instead, he sees the much more likely negative scenario of showrunners using the technology to replace the tasks of entry-level writers. For instance, an AI tool could outline the structure of a police procedural with suggested characters. Or for a comedy, AI could brainstorm ten specific ideas for a premise.

“Now it couldn’t work it into an episode and write a good joke, but it could generate the idea super quickly,” Gioia said. “Honestly I think it will probably reduce the size of these writers’ rooms, but ultimately in the long run there will be more writers and more people doing creative activity as a result.”

Gioia’s father is Dana Gioia, a former poet laureate of California and a noted literary translator and critic. Gioia described growing up with his dad like having his own large-language model complete with hundreds of poems that could be pulled up and recited from memory.

“I don’t think he sees [AI] as a threat to legitimate human creativity,” Gioia said. But his father does see it as a perhaps overdue disruption to the kind of business models that have been built on creative industries.

“When you actually try to do really difficult things with these models, you find out how difficult it is,” Gioia said. Although AI can spit out a serviceable outline or script, actually funny jokes and dramatic tension still need a human touch.

“I think that would make you rest assured that humans are going to be in the loop for a long time,” Gioia said.

Gioia said positioning AI as a central antagonist is a useful rhetorical strategy for opponents but one that elides the very real potential for augmentation and support, instead of replacement.

Not everyone is so sanguine about AI. A growing number of artists see this exponential drive toward efficiency and automated production as inherently at odds with the work they do.

Performance artist Kristina Wong made these concerns about AI a central theme of a June commencement speech she gave to recent graduates of UCLA’s School of Arts and Architecture.

“I ask you, graduating class of 2023, as you emerge into the world, what is that radical imagination that you have that no robot or AI can replicate, and how will you lead with that heart and that human intelligence?” the SF native said in her speech.

In an interview, Wong said she has played around with the technology, using it to help brainstorm images and text for a picture book she’s writing about Asian American activism. But when she asked ChatGPT to write a story about her, “it spit out this hackneyed immigrant narrative that I haven’t lived.”

Although she takes some solace in the fact that the platforms can’t write anything super funny just yet, she and her colleagues realize that the technology is constantly improving and rapidly encroaching.

“The only thing I can say to other artists who are panicking right now is the reason why [AI is] so exciting to people is because it feels so real. But there’s one thing that is even more real. Which is real flesh and blood,” Wong said.

The platforms themselves tend to generate very bland, flat writing—in part because instead of original experiences, they rely solely on derivative ones.

Additionally, the autocomplete nature of its mechanism means that the generated text has a bias toward cliché. It’s the reason why many writers believe these programs are incapable of coming up with something fresh, original, or moving. At least, for the time being.

. . .

There are some artists, like Halim Madi, that argue for AI’s ability to stretch our creative muscles past existing cultural or internal limitations.

A San Francisco–based poet, Madi sometimes plugs his verses into the program to see what it predicts he will come up with and uses that as a road map to go in a different, more surprising direction.

With the continual scroll of text that is generated by AI platforms, he imagines writers and poets using the technology to become more like sculptors, shaving off words to reveal a poetic truth.

“When you have these very powerful engines that are in a way relentless, it somehow awakens a part of us that we didn’t know existed,” Madi said. The feeling is not totally unrelated to the psychedelic experience, which can create a fresh layer of powdered snow on the well-worn ski tracks that make up one’s typical thought patterns.

Madi’s new book of poetry, Invasions, is a collection of his efforts to strike back by replying to robotexts with his own poetry. His next step is using that volume of data to train an artificial intelligence model to reply to spam texters using his own voice.

“It’s the ultimate subversion. Now I’m using artificial intelligence to answer robots,” Madi said. “It feels like insanity, but there’s also something about it that makes me laugh, and that means there’s potential.”

It’s tempting to compare AI to other technological advances in the art world. For instance, the invention of photography initially led to consternation from portrait painters who thought it meant the death of their field. What resulted was the development of photography as its own form of art and the rise of impressionism as a reaction to the technological shift.

It’s a comparison that Barry Threw, executive director of the SF nonprofits arts organization Gray Area, thinks is useful but also limited. For one, he said, who took a photo is a lot more clear than what creative labor went to creating an AI-generated image.

Threw agreed that any new technological innovation creates the opportunity for new forms of creative expression. In fact, Gray Area hosted one of the first public exhibits and auctions of AI-generated art back in 2016.

More recently, the organization hosted an event featuring artist Sarah Friend, who used an AI model to generate erotic images of herself as part of a work called Untitled. The project is meant to explore consent, vulnerability, and how sex work is being warped, revalued, and disrupted by technological innovation.

But Threw’s enthusiasm is somewhat tempered by the real impact these models are having on creators today. Without robust national support for the arts, creators have had to use their skills in ways to subsidize their ability to create art, often formulating the content scaled and monetized by tech companies.

His fear is that the increasing use of AI models in creative production means speeding up the slow squeeze of radical experimental work out of the culture.

“There has been a wholesale erosion of the societal and cultural support systems for creatives and artists over the last fifty years, and this is only an accelerant to that,” Threw said.

. . .

I’m starting to ask myself whether it’s time to start learning to love the robot, or to continue to coexist uneasily.

Recently I had the opportunity to mentor some aspiring high school journalists and decided to conduct an unscientific straw poll on how many used AI regularly. Nearly all of them raised their hands, although they swore they weren’t using it to cheat on their homework.

I was in the process of brainstorming potential interview questions with a student, who as an experiment typed a few words into ChatGPT and turned her laptop around to show a full list of fifteen interview questions tailored specifically to the subject at hand.

“Wow,” was really the only response I could muster.

I’ve done my own interrogation of ChatGPT to see if it could help me navigate the tricky path between fear and opportunity that it poses. For its part, the platform insists that it can never fully replicate human qualities, even as it comes up with longer and longer lists of how it’s possible to do just that.

Pushing against the tide feels simultaneously ineffectual but entirely necessary. After all, it’s only human to delay the inevitable.

I had some difficulties trying to put a bow on this piece, so I decided to embrace the robots and asked ChatGPT to come up with three alternatives for an ending. Here they are:

“By harnessing AI’s potential to spark ideas, streamline processes, and navigate unexplored realms of imagination, we can carve a path toward a future where both human and machine coexist harmoniously in the world of creativity.”

“In this rapidly changing landscape, it is our ability to adapt and evolve that will determine the future of creative endeavors, steering us toward a symbiotic relationship between human vision and AI ingenuity.”

“By fostering a symbiotic relationship with AI, we can build a future where human creativity and technological innovation coalesce, enriching our lives with a harmonious fusion of human heart and machine intelligence. In this shared journey, we have the power to craft a future where creativity thrives and resonates with audiences in ways we could never have imagined.”

It’s probably worth noting that none of the options involve fully shirking AI, but feel free to choose your own adventure. Notably, though, they all seem to be leading to the same destination. ♦

[Editor’s note: This article was co-published with The San Francisco Standard.]

Kevin Truong is a San Francisco–based writer who currently works as a reporter at the San Francisco Standard. A proud UCLA graduate, he made his way north to the City by the Bay, where he enjoys freshly caught Dungeness crab, Dolores Park hangs, and perfectly foggy Sunday mornings.

Jane Elliott enjoys the tools of digital illustration and animation as well as creating traditional works. She lives in San Francisco with her overgrown houseplants and a tenor sax named Athena. She loves foghorns, mysteries, poetry, a good whiskey sour, and playing with Photoshop and After Effects.