Observations from San Francisco’s tech world.

by Cassie Wild

I’m waiting in line to get some eggs and coffee at a cafe in the Mission. It’s one of those younger businesses on the outskirts of gentrification, the forward guard. The line stretches far out the door, but it moves fast. Nevertheless, I overhear fifteen minutes of a strained conversation between two twenty-or-thirty-somethings standing behind me.

As their conversation progresses, I grow more and more angry at them. One describes his recent two-week vacation to Japan, where he did some “excellent” skiing with his girlfriend. The other asks some open-ended questions, and is in turn asked about who he goes with on his annual trip to Park City. (I’d never heard of this place, looked it up later, and it’s another ski destination.)

Park City replies, jokingly, that “thirty-five of his closest friends” rent out a mansion for the weekend every year, which costs, he says, about thirty thousand dollars for the weekend. He says that it is a far superior experience to renting out a condo, and splitting that cost among that many people is “doable.”

I now know that they, like me, are tech workers. I wonder who owns this mansion, and what they do with the $30k they make in a weekend. I wonder if a couple of those shortest-term tenants per month covers maintenance costs and property taxes associated with holding the land.

At the counter, a tall, dark-skinned cashier takes an unending line of orders. Behind him, a small person wearing a tie-dye shirt with the words “GENDER IS A SOCIAL CONSTRUCT” across the front makes hand-over-hand espresso drinks and coffees. Neither one is smiling. I wonder if the cafe provides them with health insurance.

The conversation behind me turns to catching up at work after a vacation. The other man is telling Park City that during his trip to Japan he “went cold turkey” on internet access. “Cold Turkey” didn’t check any communications from work, and now he is concerned about being “scolded” for it on Monday. Park City boasts that he hasn’t gone a lengthy period without checking work email in years. Cold Turkey hurriedly justifies that since “I work my ass off for these people” he deserves to be able to completely disengage once in a while.

At this point, my curiosity is too great. I want to know what has allowed them to preserve the delusion that they “deserve” anything.

I want to know if they’re both male-presenting. I want to know if they’re both white. I turn, pretending to look at a sign across the street. They are.

The one on the right (Park City) is a Mark Zuckerberg type: orangey hair, glasses, close-set eyes, a straight and sharp nose. The one on the left (Cold Turkey) is slightly shorter, more muscular, wearing a black vest, with dark hair and dark eyes. I can’t see him as well, but something about the set of his eyebrows, the line of his shoulders, the shape of his lips—and the past few minutes—has given his appearance an arrogant cast.

I cover my 140-degree turn by making a joke to my partner, who is focused completely on his impending breakfast, about the sign behind us almost (but not) reading “Gemini,” his star sign. Unsurprisingly, he doesn’t care at all. Neither do I, because the tech dudes don’t notice that I saw them, or possibly even that I exist.

Cold Turkey languidly reveals that he is in the process of firing one of his teammates. Park City asks him what it feels like to fire people. He says this with an edge of true curiosity creeping into his voice that was notably absent during the descriptions of skiing in Nagano, and I feel like I can see his expression turn slightly feral. Park City goads Cold Turkey into elaborating. I imagine a twitch of the upper lip, maybe nostrils slightly flared. He wants the story of this power. He wonders aloud how it is that every time they speak, Cold Turkey has recently fired someone.

Long-suffering Cold Turkey “inherited” the woman he wants to fire. She was here before he was. Everyone else on his team, he claims, has given him no problem. Coincidentally, he seems to have collected them all personally. The doomed employee, Cold Turkey explains, is the kind of person who works very hard, and thinks that putting in effort is enough. She doesn’t get results, though. I wonder what metrics Cold Turkey uses to evaluate success. Is he colonizing his workplace? I wonder what his management style might be. The callous summary of his colleague betrays no empathy.

I can imagine what Cold Turkey’s “results” might entail. From what I’ve seen and heard in my years of working in technology, quantifiable metrics are often upheld to the exclusion of everything else (even, occasionally, the law). Executives love metrics, and the pretense of information it grants them. Management loves the stability that “provable” facts provide. Individual contributors love being left alone—and that most harassment ends where numbers look good.

What these numbers fail to acknowledge is all the information carried away in the expressions and sentiments of former (and often current) employees, especially as they are displaced by the ever-more-cutthroat profit-seekers that growing companies accumulate.

Who can tell you why certain companies have such poor retention and high churn? The fired workers, those let go on mathematical and impersonal justifications their superiors can hide behind, understand all those things that invisibly translate into any bottom line. But it is executives who make the choices to write the checks, and it’s easier to call these complaints noise and ignore the problems they cause.

Since any fallout will happen far in the future, many C-suites can comfort themselves with fantasies of moving on to the next lucrative green field by then. As long as stakeholders make enough money on their exit to lay track to the next destination, they don’t need to care what destruction they wreak. With rare exceptions, they are incentivized against asking the question of whether these conglomerations of human labor we call startups ought to even exist. They care even less about the motivations and incentives that trickle down to the Park Citys and Cold Turkeys in this city and generation, and what it means for the future.

In those exceptional cases where existential decisions are made from the heart as well as the head, invariably the companies struggle to survive, leaving mostly a morass of writhing capitalists trailing in their wake. VCs don’t care—there are always more piranhas in the sea.

As I approach the counter, their conversation finally dies down. They will order next, freed from the shallow oblivion of their one-upmanship, testing who can climb the ladder they cling to faster. Cold Turkey utters the final words—

“San Francisco kind of sucks.”

My eyes widen. I turn to face my partner, standing beside me. He continues to stare straight ahead, fixated on the food in his very near future. My partner’s love of San Francisco is white-knuckled. He and I have argued many times about the merits of living here. He’s on his seventh year in the city and showing no signs of restlessness or discomfort. I am on my third and can’t believe it’s only been that long.

Cold Turkey, a blight upon this city, has just said exactly the same thing I’ve said so many times. I found the adjustment, moving here, to be very difficult. I know that change is difficult for me; it’s difficult for everyone. But I moved here without asking permission from the community I was moving into, and am confronted with that fact every day.

Though I interviewed for the apartment I live in, I, and it, was already plugged in to the world of an invasive species that keeps on propagating. I may have tried to make good here, but the damage caused by the same forces that brought me to this place is so obvious, so talked-about—the only, if not final, word on the street–and so widespread, that doing enough good to create any semblance of balance feels like an impossible goal.

And yet, people in the city are still fighting towards it. During my time here, I’ve made friends I admire, who care about things, and who work to make a better world. I’ve met with citizens who are trying to create public housing legislation, and better government. The voters make real changes. People use technology to build tools that help get people the basics, the things they need to live. Others help out to take care of people who need help getting even footing. Good people are everywhere.

Here, I have the beginnings of a community. Yet nothing I have built could ever equal the richness of what is being displaced.

What I’ve heard, over and over, was built by people connected by families, and people who knew their neighbors, and not a bunch of single newcomers looking for company through the formal impersonalism of computers.

I order my food. My meal costs “ten and a penny,” and I give a ten and a one—eleven. The cashier hands the one back to me, and I put it in the tip jar. That one dollar settles down like the end of a shrug. I tell the barista I like their shirt and they smile at me. I do like the shirt. I agree that GENDER IS A SOCIAL CONSTRUCT (along with almost everything else). I wish everyone could be as brave and genuine as I imagine a person who chose that armor to be. I desperately want allegiance with them. It’s a hopelessly naive thing, to project political and ethical purity onto a young person with a low-paying job and a counter-culture mode of dress, but I do it anyway.

I’ve never worked a service job, and don’t know what effect I’ve had on this person. Smiling must be a part of their job: customer service. I tried to brighten their day, but it doesn’t feel like it matters. But why did I try? To prove to myself that I’m not like those monsters who don’t give their easy money to bail funds and immigration defense attorneys? But if we hadn’t moved here, if the reasons we moved here weren’t a part of the human organism, those things would not even need to exist. We bring the establishment with us, and as we move in, we displace the existing life and ties of a community.

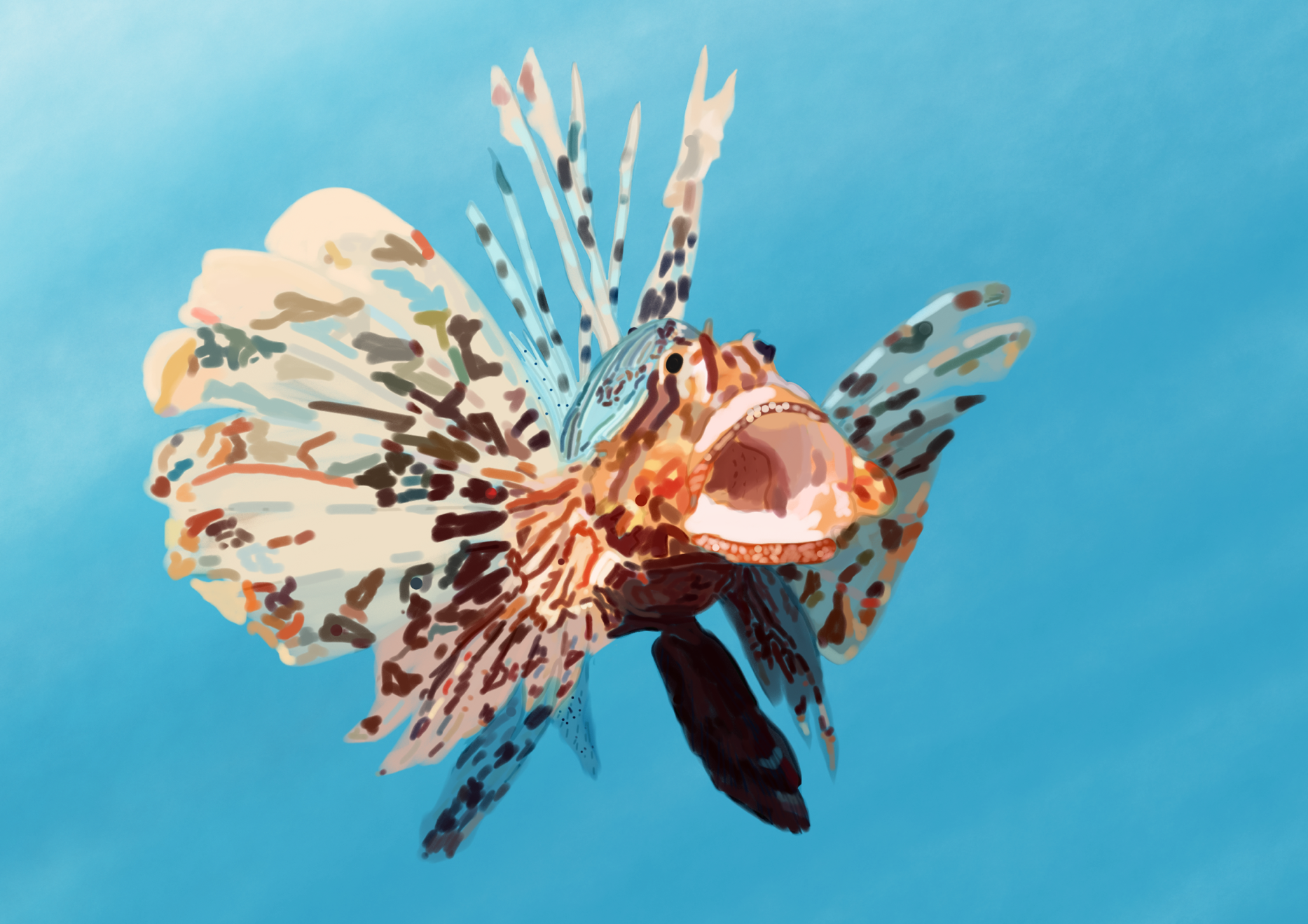

I’ve always felt sorry for the lionfish in Florida. They are an invasive species, transplanted across the ocean by people. And yet other people cry destruction of the native environment in the face of the lionfish’s success.

How is the lionfish’s success unnatural? It was their beauty that captured our attention, their attractive qualities that led a large, human mammal to transport them to a new environment, a force like a seasonal jet stream. And the lionfish thrived.

I don’t know Park City and Cold Turkey at all as individuals, but I see their place in the order. They are first-generation lionfish, brought here by some other, bigger creature. Executives, a plutocracy flush with cash that needs to change hands in order to maintain its value, had to move more workers into this place. They made no provision for preserving the environment. They just ate it.

Maybe I could feel the beauty and depth of these lionfish-men if I could see them in their original habitat. Something beautiful in a crowd, strong by contrast with what surrounds it, becomes ugly as a dominant mass—all that’s left, all alone. Here we are, in this line, and all I see is two monsters locked a confrontation with each other’s facades, in the midst of a city that their very existence pollute—then erases.

After ordering and sitting down, I watch the two of them walk to a table outside with their matching girlfriends, and it makes sense why two people who so clearly hold no affection for one another would spend time in each other’s presence. Something else holds them together: a community, small but growing. They are trying to make it here. They are surviving, but they are not home.

I moved here, to this place with these people, despite my misgivings. I truly believed the company that hired me was invested in creating a better future. I was excited to be the hero in the adventure of life, or on the hero’s team. Then I got here, and saw that’s not what I am at all. What I am is much more like a henchman in the rearguard of the villain’s army.

There is a lot left for me to learn at my job, but I’ve heard the most important lesson loud and clear. Even before coming here, I felt trepidation about moving to a place that was so dominated by one industry—my industry. I knew that even as a woman, I would be The Man.

After weeks of crying, hair-pulling, and weighing the consequences of desertion, I tried to change sides. Fueled by a mix of personal experience and the gravity of obligation, I began training to become a hotline counselor at San Francisco Suicide Prevention. It’s an operation that subsists on the volunteer labor of hopeful people of various stripes. It’s a place whose formal organization has existed for decades, but has persisted in one form or another for as long as people have.

I go in at least once a week, sometimes more. I sit in a call center at an anonymous location and wait for the phone to ring. Sometimes it’s quiet. Sometimes it rings so much, so frequently, that it’s all I and the other counselors can do just to pick up the phone, let people know we’re here, assess their suicide risk, and ask them to call back later. Sometimes someone calls, desperate.

During these most serious calls, something shifts inside me. I can’t see what’s around me, or of course, around them. Sometimes I close my eyes. I listen for every tremble in their voice. Word choices matter, but also don’t. If they falter, I decide to stay quiet or to offer continuation. I ask about the background noises I can hear. I alternate—sometimes stern and forceful, sometimes gentle and concerned—following their need.

I become only my voice, and my voice turns liquid, pouring through the receiver, reaching out to feel the humble, secret knife slices that reveal themselves, with all vulnerability, to my sounds and silences. Surprisingly often, the pain of a stranger does not feel alien to me. I can feel something like what someone else feels. The memories of my own struggles rise up, renew, and remind me of the gifts I used to survive them. My work there is to try to pass these through.

Some nights after I’ve come home from a shift, tired and quiet, I’ve thought—doesn’t convincing someone in pain to go on living create a greater amount of pain and suffering? Suicide hotlines have never been “proven” to have a positive effect. And yet, I counter, how could we ever measure such a thing? This kind of value cannot be measured by the cutting-edge tools of science or the judgment of a person who takes everything from a city and then spits on its name.

Almost everyone who calls a suicide hotline wants to live. That’s why they’re calling. They want to live and they want to die. It’s a natural thing to feel, if you can admit it. The job of a person on the other end of a phone that only rings when someone is in pain, is to just be there and share that pain.

You take on a little bit of the pain, so someone else can move forward with a little less of it.

In reverse of the well-known aphorism that a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts, pain divided between two people becomes smaller than each share would be combined. I feel my own pain fade away as I hold on to someone else’s.

The logo of San Francisco Suicide Prevention is not a phone, or a smile, or an ambulance. It’s two right hands reaching out to each other. I can tell by the thumbs, positioned on opposite sides from one other, that they are the same hand—and thus two different people, ready to hold on to each other. Our thumbs, we’re told, are what separate us from animals. Our ability to hold things makes us human, and lets our brain pick apart puzzles unthinkable without these hands.

Supposedly, I am a problem-solver. I was invited to join the pantheon of exalted West Coast programmers for exactly that skillset. But listening to hundreds of people in pain, soothing their emotions and simply being there in their dark moments, while listening with the other ear turned towards problems of industry and media, it’s become clear that in modern life we’ve run headlong into a split-brain problem.

As technologists in the business of Silicon Valley, we tune our minds in to solving problems that end up creating more problems. Our metal powers are used for amassing more mental power. Sell faster, sell more, learn everything about each other to provide what we want, but not what we need. We want to forget our feelings. We want not to question the entire enterprise.

That is the allure of a computer. With it, we can keep retreading our tracks, seemingly forever, seemingly moving forward—away from yesterday’s issues, into tomorrow’s promises. With a computer, we can ignore the sacrifices of the present.

On the other side of a computer terminal, we keep our distance. At the same time, we can believe we are bringing efficiency to all sorts of problems—taking care of so many “needs.” Lonely? Here’s a device that can get in touch with anyone, anytime, so you’ll never feel like it’s a priority to be with them. Horny? Here are trillions of images of porn and an endless carousel of potential hook-ups, so there’s no need to try for courage, or for intimacy. Bored? Here are unlimited video games, movies, and tv shows for when social media turns out to be less satisfying than fast-fading memories of real friendship.

Suddenly, we imagine, we can solve the problem of pain millions of times over without hurting much at all ourselves. We will just make the tubes, someone else will speak the incantations.

For all its innovations, the modern industrial revolution has yet to produce any idea that does not favor quantitative qualities, and that does not threaten our survival at least as much as it seems to ensure it. An emblematic example: we have voice recognition software to enhance ordinary people’s command over their world by issuing verbal instructions to handheld devices which delightfully or frightfully respond (depending on your attitude).

This same class of technology is used to create digital “voice prints” of incarcerated individuals, which are used to improve the accuracy of voice recognition software. These are stored, even after that person has served their time. In sharp contrast to a free person’s experience, the phones available to prisoners—paying with a vocal fingerprint to speak to their loved ones—can bar them from basics such as free access to 800 numbers. Crisis lines, by the way, are in that category. The powerful group reaps the benefits of a technology, and an oppressed group is forced to sacrifice, invisibly, for those gains.

A few weeks ago, my shiftmate at the hotline referred to my two years in the Mission as five San Francisco years (“like dog years,” another counselor joked). I thought about my 2-Mission-5-San Francisco-years. When I first arrived, I was bowled over by how much technology has veined its way through every billboard, every subway wall, every head bobbing around plugged with a pair of AirPods, and so many overheard sidewalk conversations. Now I am getting used to it, but the creeping horror of its ubiquity has never disappeared.

As a group, the tech industry does not value the size of someone’s sadness, the shape of their invisible impacts, or the character of their heart—all the things that can be felt but not measured. Technology we create is shaping the modern world. It matters how we use it. It matters what we value.

We pay people hundreds of thousands of dollars to move packets back and forth, but we pay almost nothing to ensure that what is sent and received has the quality of goodness. We do not pay the cost of uplifting people from their misery. We look at our screens, and away from each other, and we choose, mostly, exactly what we want to see and hear.

Kindness, like courage, exists only in the face of a challenge to it. If we spend our time avoiding the difficulties of being together, we allow love and kindness to be crowded out. Eons of humanity’s wisdom tells us, over and over, that these are the things worth saving about us. Still we choose to uphold computation, logic, and attention-destroying psychological manipulations over simple truths.

We can change yet. Threats approach from many angles, and enormous challenges loom ahead. We are backing up against a wall—of climate change, of logical exhaustion, of helpless apathy, of vicious bipartisanship, of bigotry unchecked—but it isn’t too late. It may be freezing cold, but for now, you can still swim on the city’s shore.

San Francisco doesn’t suck. It’s being sucked dry. ♦

Cassie Wild is a regular contributor at the magazine. She is a programmer in a love/hate relationship with her computer. Originally from NYC, she advocated for this magazine to be called The San Franciscker. She’s okay with the name we chose though.