What it’s like being a journalist during the pandemic.

by Elena Kadvany

My breaking point came late one Tuesday night, about a week into the shutdown. I had just finished reporting (virtually) on a local school board meeting after multiple 12-hour-plus workdays, and the thought of writing one more word about the pandemic made me feel like crawling into bed and never re-emerging. I burst into tears, still holding my laptop, the cursor line blinking with anticipation on a blank Word document.

Covering the coronavirus is a marathon, not a sprint, our editors had been repeatedly telling us. Despite their advice, I had been in full sprint mode, subject to the whiplash of constant breaking news, long days that blurred together, updates from our publisher on the declining financial health of our newspapers, and anxiety that yanked me awake at 4 a.m. (my answer to which was getting out of bed to work).

With no office to leave at the end of the day, my tendency to overwork had even fewer boundaries than usual. I’d finally decide to close my computer, relax my scrunched-up shoulders from their new home next to my ears, and open the fridge to make dinner, if I had any appetite—and then get a text about another breaking story that needed to be reported on, now. Work quickly seeped into my home life in a way it never had before.

Some days I felt so moved by the news and energized by my duty as a journalist. I’m performing an essential service! These stories matter! But more often than not, I’d wake up in an unmotivated fog. The guards that usually keep watch over my mind’s most difficult residents—anxiety, self-criticism, perfectionism—suddenly went on an unannounced, extended vacation.

This all culminated in that late-night breakdown during which my boyfriend told me what I already knew: If I don’t take care of myself, I’ll burn out, and I won’t be able to bring my best self to the stories I care so deeply about. The coronavirus has made the urgency of that conventional wisdom clearer than ever.

This feels like a historic moment to be a journalist, something I’ll tell my kids about. Co-workers have compared the pandemic to 9/11 or the 2008 financial crisis, only worse. Unlike a terrorist attack, natural disaster, or any of the emergencies we try to prepare for, the pandemic, pervasive and all-consuming, lacks a clearly defined passage from crisis into recovery.

For journalists, this means we can’t ride the adrenaline rush that comes with covering major breaking news, when you drop everything to throw yourself headfirst into a story and then emerge, breathless and exhausted to the bone but knowing you’ve provided a critical public service. This rush is what I love about being a reporter. I once pulled a very cold all-nighter outside a San Jose jail waiting for the release of Brock Turner, whose infamous sexual-assault case I had covered intensely since his arrest at Stanford University. At dawn, I drove home to file that story, then raced back to the jail to report on a large, emotionally charged rally protesting his early release. It felt like some of the most important work I’ve done (and on the fewest hours of sleep).

With an event of the coronavirus’ magnitude, you go through that cycle again and again, but without the time to stop, breathe, and reset.

How have I resolved working in this endless grind? The honest answer: I haven’t. I’ve adapted, and leaned into things that I know shore up my well-being—walks, regular therapy, asking for help when I need it—but the coronavirus continues to be the most demanding story my co-workers and I have ever covered.

. . .

My editor asked me early on in the shutdown if I felt comfortable continuing to report in person. I decided I wasn’t. Information about the virus was developing by the day, and I worried about potentially exposing myself or others. A big part of me felt guilty about that choice. It felt antithetical to my obligations as a reporter.

As journalists, we don’t call firefighters to ask what’s going on with the burning house down the street. Notebooks and phones in hand, we literally run toward the flames. We go into people’s homes, workplaces, schools, and community spaces to ask probing, important questions. We prefer in-person interviews because there’s no substitute for the richness, the unexpected anecdotes and color that come from face-to-face interaction. We bear witness, in person, to life and death and intimacy and banality.

For the first two months of the shelter-in-place order, I was instead bearing witness from my small two-seat kitchen table. The beats I cover, education and restaurants, happen to be among the most upended by the pandemic. The stories that need to be told about the ripple effects on both schools and the food industry are countless. It’s admittedly much harder to do that from a distance.

My days were spent talking to sources on the phone or via Zoom, writing and rewriting and watching my inbox for the latest public-health announcements. Instead of interviewing a chef in the kitchen of her new restaurant, I picked up food in plastic to-go containers and talked to masked staff from behind plastic partitions about what they were doing to survive. (I never thought I’d write about restaurants selling toilet paper and nitrile gloves, but here we are.)

From afar, I followed schools’ overnight shift into online education and the disproportionate impacts on low-income families of color, many of whom lack the resources and internet access for successful distance learning. These disparities were echoed in my own reporting. Affluent parents and students were easy to reach and eager to talk about the calculus sessions and yoga lessons they were organizing on Zoom. Parents who don’t speak English, work multiple jobs, and had never used Zoom before the shutdown were harder to reach when I couldn’t knock on their doors in person.

. . .

During an all-staff Zoom meeting in March, we learned that about a dozen of our co-workers at Embarcadero Media would be furloughed or laid off. I watched the grid of faces on my screen take in the grim reality of the state of our industry. With community events canceled, businesses closed, and the local real estate market on hold, our advertising revenue plummeted. We stopped printing three of our four newspapers. Luckily, our company eventually received a federal Paycheck Protection Program loan and other grants that provided some relief and allowed us to bring back two of the print editions and some furloughed employees.

During a public-health crisis, our job of providing timely, accurate information is more important than ever. But it’s also never been more under threat of extinction.

Local journalism was in crisis long before the coronavirus hit. Over the past 15 years, more than one in five newspapers in the United States has closed, according to research by the University of North Carolina’s Hussman School of Journalism and Media. Even more have folded during the shutdown. My Twitter feed has been full of reporters posting about layoffs.

Imagine cities, schools, companies, public agencies—entire communities—functioning without the sunshine that local journalism brings. In 2017, our reporting uncovered that top Palo Alto Unified School District officials had neglected to notify their unions that the district planned to cancel planned raises, an avoidable mistake that cost taxpayers millions of dollars—and one that neither the district nor the union wanted in the public eye. Sometimes the impact stems from more subtle, bread-and-butter coverage: a profile of the new chief of police, dispatches from high school football games, the story behind a new restaurant opening in the neighborhood.

As we’ve sheltered in place, connecting to the outside world through our computer screens, reliable sources of objective information have been more crucial than ever to stay informed and engaged with not only the latest news but also our broader communities.

. . .

Eventually, that almost visceral journalistic itch to bear witness in person propelled me back into the field. In early June, I interviewed restaurateurs when they reopened for outdoor dining, covered powerful Black Lives Matter protests, and got up before dawn to follow boxes of produce from the warehouses of a Bay Area food bank into the hands of a staggering number of people who need food assistance during the pandemic.

What has struck me in almost every single interview I’ve done during the shutdown—whether it was the restaurant owner deciding to use his own savings to pay his undocumented staff, the single mother worried about her autistic son falling behind in school while she worked long days at a local grocery store, or the high school senior who didn’t know if she’d be walking across a stage to receive her diploma but decorated her graduation cap anyway—has been a sense of resiliency amid chaos. This has been described as our “new abnormal,” which resonates with me deeply now that I’m reporting in person again.

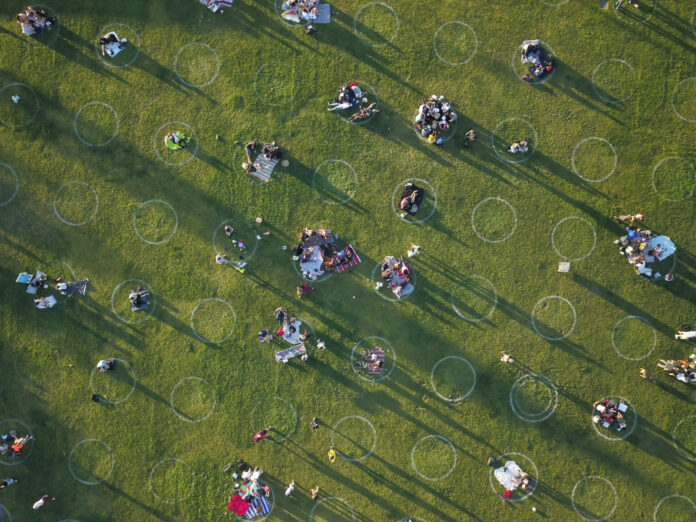

When I sit back down at my small kitchen table to write, I conjure up the scenes I bore witness to that day: masked restaurant servers bringing steaming plates of food to tables set six feet apart, Black teenagers marching with fervor in the streets for racial justice, parents staying up late to tell school leaders on Zoom their anxieties about schools reopening this fall. I take a deep breath, and looking at that blinking cursor on the blank Word document, find the words to tell their essential stories. ♦

Elena Kadvany is a local journalist and Bay Area native whose true loves are dumplings, writing, and her cat, Leo. She writes about education and restaurants on the Peninsula for the Palo Alto Weekly and has been published in the Guardian, Bon Appetit’s Healthyish, and the Six Fifty.