Getting to know the gardeners of Alcatraz, past and present.

When Matt Lederman first started volunteer-gardening on Alcatraz, he was met with mild incredulity by friends. “They were like, ‘You volunteer where?’” he says with a smile, recalling his first work trip to the island in June 2022.

It’s a clear Thursday morning just before the chill of winter has set in, and we’re cruising across the bay on the Alcatraz ferry. If you’ve ever visited the island, you may recognize the vehicle: a triple-decker watercraft capable of carrying up to five hundred passengers and usually teeming with camera-toting tourists. However, on the 8:20 a.m. trip from Pier 33, we’re the only ones on the boat, strategically poised to arrive before the first wave of visitors.

Lederman, a resident of the Outer Sunset, is one of the newest volunteers with the Alcatraz Gardens Stewardship Program, which is dedicated to preserving the historic green spaces on the island. We’re joined by two longtime volunteers, Barbara Howald and Marney Beard.

Beard, a retired technology professional, was as surprised as Lederman’s friends when she first learned about the program online, back in 2005. “The one time I’d been to Alcatraz, in the late eighties, it was completely overgrown,” she tells us. “I thought, That’s crazy! You can’t go out to Alcatraz and work at gardens.”

Beard and Howald have been working the gardens for seventeen and fourteen years, respectively. Both retired and Castro residents, they didn’t know each other before joining the volunteer program but have since become good friends. The two women make an effort to come out to the island most Wednesdays and Thursdays, which are the dedicated days for gardening. Their tasks vary day by day, season by season. In spring and summer there’s always pruning and watering to do. In the fall, Howald says, when the bird nesting season is over and the protected nesting habitats reopen to the public, they clear out the growth that has accumulated over the past six months.

Like many seasoned volunteers, they’ve built up an extensive knowledge of the island, and they delight in sharing nuggets of history with curious tourists. Beard starts telling me about the early days, when the US military first brought shiploads of soil to Alcatraz, but she stops short. “You’ll hear more about this when Shelagh takes you around,” she says, as the former prison looms into view.

. . .

Gardener and horticulturist extraordinaire Shelagh Fritz has led the stewardship program since 2009. As program manager, Fritz develops each day’s schedule based on the group and their experience. Noting the island’s long history of volunteer gardeners, I ask if it’s ever been anyone’s full-time job to manage the gardens at Alcatraz. She smiles and replies, “Me!”

Fritz is uniquely qualified for the job. With a degree in horticulture and a previous life tending the centuries-old gardens at Syon Park near London, her expertise is not only in the science but also the history of the gardens she maintains.

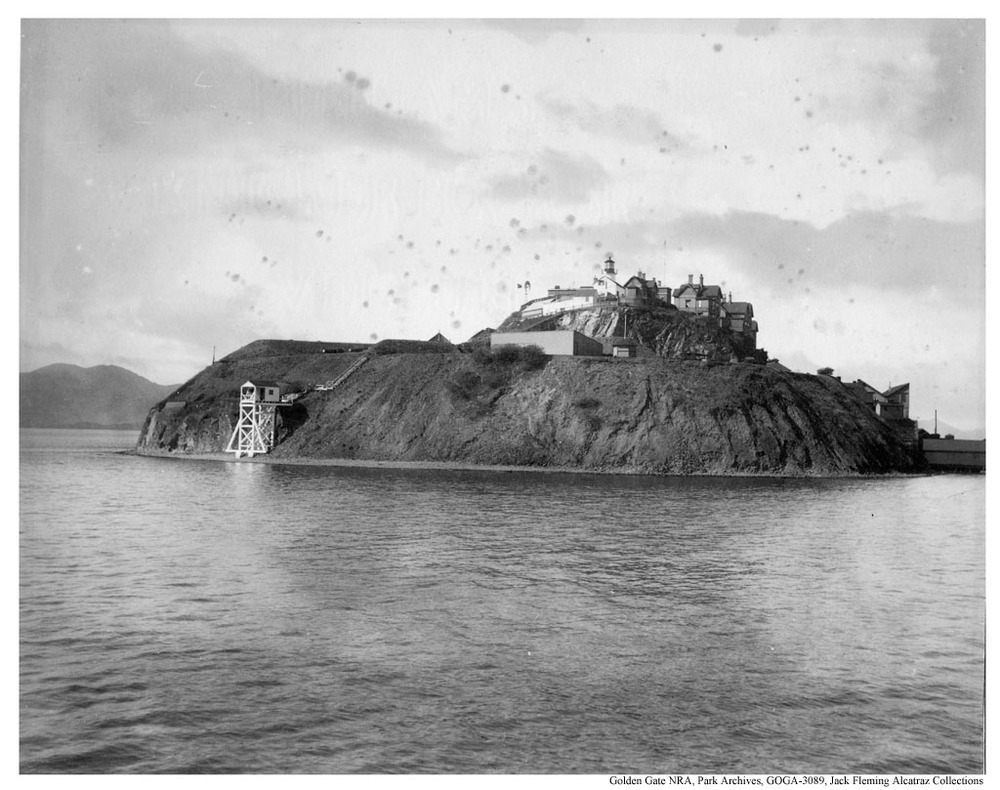

The first photo she shows me, after opening the toolshed for Lederman, Beard, and Howald, is of Alcatraz in its natural state, pre-1850s. Back then, it was nothing more than a bald mound of sandstone sticking out of San Francisco Bay, incapable of growing anything but sparse foliage. “There’s no topsoil and no fresh water, other than rain and summer fog drip,” she says. “It really is the most unlikely place to have a garden.” The island’s only discernible inhabitants, gulls and cormorants and other seabirds, were the sole rulers of the rock.

In 1850, the US military set out to build a trio of fortresses to protect the bay in the event of a foreign invasion. Unlike its proposed counterparts at either end of the Golden Gate Bridge, the fortress at Alcatraces (as it was named then, Spanish for “pelicans”) required considerably more effort to erect: engineers carved and leveled the land, shipping building materials, food, and water from the mainland. Military officers’ houses were built on the east side of the island in an attempt to protect them from the biting bay winds. As the site established itself as a military post, its first residents brought their wives and children to live on Officers’ Row, making a comfortable, if not unique, home of the 22-acre island.

These military wives were the first gardeners of the island, Fritz tells me, as we ascend the path from the ferry landing. When soil was brought to Alcatraz from Angel Island and the Presidio to hold cannons in place, residents resourcefully snatched some of the soil for their own gardens. They planted seeds and cuttings they had brought from back home, giving Alcatraz its first semblance of a garden.

Today, at Officers’ Row, the former military officers’ homes are long gone, but their garden terraces remain, and the descendants of those first seedlings endure. “We have irises and roses that were first introduced to the horticulture trade in the late 1800s,” Fritz says proudly. “There are all these wonderful heirloom plants from the military and federal penitentiary days.”

Even in late fall the gardens are bright with blooms. Delicate sweet peas and daffodils dot the walkway. These are cutting gardens that yield colorful flowers destined for vases and bouquets, Fritz says. The decision of the military wives to tend flowers instead of vegetables may have served to brighten the cold, windy days on the island, “and I personally think the women wanted a reason to go grocery shopping in the city,” she hypothesizes.

Over time, Alcatraz’s duties as a fortress diminished, while its number of military prisoners grew. By 1909, the citadel at the top of the island was torn down and rebuilt as a cell house. It was in the 1920s, during an attempt to soften the prison’s harsh appearance, that Alcatraz’s inmates—at that time not dangerous criminals but mostly wayward soldiers—first contributed to the landscape, planting Monterey cypress and eucalyptus trees on its windswept hillsides.

The transition from military prison to federal penitentiary occurred in 1933, a period made famous by notorious inmates such as Al Capone and George “Machine Gun” Kelly. For horticulturists like Fritz, though, one of the most notable names of this era is Fred Reichel, secretary to the warden, who took it upon himself to maintain and cultivate the gardens, consulting horticulturists and bringing in climate-appropriate species from the Mediterranean, Mexico, Australia, and New Zealand. Fritz points out Reichel’s contributions as we continue along: the New Zealand Christmas tree on the western side of the island was planted under his direction, and so was the magnificent pride of Madeira, a showy shrub sporting brilliant purple flowers.

Reichel quickly realized he couldn’t maintain the island’s gardens himself. With some convincing, he eventually persuaded the warden to allow inmates at the maximum-security prison to help.

. . .

Elliott Michener and Richard Franseen found themselves on the Rock after committing a series of robberies and forgeries, and, in Michener’s case, a botched escape attempt from a federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas. Old friends bonded by a shared penchant for crime, they were ultimately sentenced to Alcatraz for an elaborate counterfeiting scheme they’d run out of Alameda. But despite their prior run-ins with the law, prison officials grew to trust them, and they were eventually enlisted to work in the gardens under close watch.

The men started out with simple tasks, like pruning the fast-growing ice plant on the western hillside near the prisoners’ recreation yard. Franseen, who had grown up on a farm, took an interest in propagating plants, and spent his work hours diligently tending to budding seedlings. Michener was entrusted to care for a small garden on the warden’s property, where he carefully crafted bouquets for the warden’s wife. The men formed strategic friendships with guards so that the guards might bring them seeds and gardening books from the outside.

“I didn’t have any botanical background,” Michener told a reporter years later. “I just learned to garden here. I got a lot of books and studied them.”

Warden Edwin Swope eventually found Michener to be such a trustworthy worker that he promoted him to the role of houseboy, allowing him a few precious hours of radio, newspaper reading, and other symbols of normalcy while on the job. All the while, Michener continued his garden duties, building a greenhouse for the Swopes, which he filled with begonias.

Franseen was released from Alcatraz in the late 1940s, perhaps with a tinge of regret. In a 1945 letter, he wrote, “I have a good job in the garden and greenhouse, and have done so much hard work on them that I’ve grown a bit attached to the place.”

After Michener was set free in the 1950s, he and Franseen found work on a farm in Wisconsin, where they made use of their cultivation skills. In a letter to Warden Swope, Michener wrote, “Dick and I are getting along well, and for the first time I’m learning how much better one can do living honestly than by, say, counterfeiting! We have cars and fat bank accounts…and we have a favor to ask: will you send us a bush of our old ‘Gardener’ rose?”

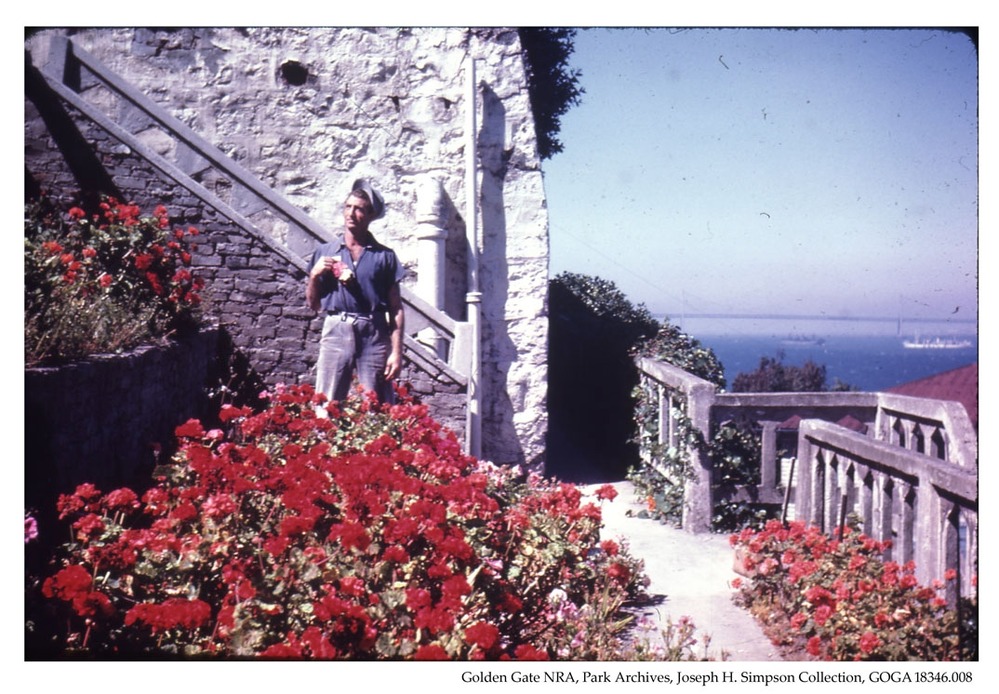

On the west side of the island, covering the hillsides and terraces between the former prisoners’ recreation yard and the frigid water, Michener and Franseen’s legacy is still very much alive: ice plants blanket the hillsides in a vibrant pink every spring, and gladiolus flowers bloom in late fall in dazzling pinks and reds. Fritz shows me a photo from the 1940s showcasing one of Michener’s gardens, a colorful plot of gladiolus, roses, and agave. Today, the garden looks almost exactly the same.

Fritz is careful to make the distinction that Alcatraz is home to historical gardens, not botanical gardens. Plants that wouldn’t be found side by side in a botanical garden (such as fuchsia from Central America and jade plant from South Africa) coexist happily on Alcatraz, sharing a common willingness to survive in this unlikely man-made landscape. From the Victorian gardens along Officers’ Row to the midcentury gladiolus and geraniums coloring the western terraces, to walk through Alcatraz’s gardens is to step back in time, slowly getting to know the individuals whose hands tended the soil.

. . .

The Rock’s last day as a federal prison was March 21, 1963. After several years of desertion and a nineteen-month period during which Native Americans occupied the island—starkly painted messages from this time are still visible on some of the buildings—the site was absorbed into the National Park Service’s Golden Gate National Recreation Area in 1972.

But ironically, Alcatraz’s first thirty years as part of the GGNRA were marked by a severe neglect of its green spaces. As the first tourists stepped off the ferry in the 1970s, they were met with skeletal trees and jungles of menacing overgrowth. The gardens, so carefully tended by the island’s previous inhabitants, were choked by weeds and ivy. With no one to water or prune the plants, the island was living up to its reputation as a harsh and desolate prison environment.

(Today, some of the island’s hillsides still offer a glimpse of what most of the island looked like during those years. Too treacherous to climb, these areas are wild and messy, overgrown with invasive species which, in some cases, were unintentionally brought to the island when soil was first imported.)

It wasn’t until the early 2000s that the National Park Service, the Garden Conservancy, and the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy came together to survey the overgrowth and make a plan for restoration. Fritz’s involvement began through the Garden Conservancy, which was tasked with providing the horticultural knowledge and research required to reconstruct the historical gardens. Meanwhile, a group of volunteer gardeners dived hands-first into the overgrowth, pulling weeds while simultaneously uncovering what surviving plants remained from the original gardens. “It was garden archaeology,” Fritz says gleefully, recounting how they’d found original irises and stepping stones untouched along the Officers’ Row terraces.

Perhaps the greatest discovery of all was the ‘Bardou Job’ rose, a rare specimen first cultivated in France in the late 1800s and likely brought to Alcatraz around that time. A century later, before restoration work had begun in earnest, a group of visiting rose experts found it growing among the ivy and blackberry behind the warden’s house. After the rare surviving variety was identified, word spread among the rosarian community. A special request came from the Museum of Welsh Life in Wales, which had been searching for the ‘Bardou Job’ for their collection with no luck. A cutting of the rose was sent from Alcatraz to complete the collection, making headlines in San Francisco and the UK, Fritz tells me. The rose happens to be in bloom during my visit: it clings to the chain-link fence encircling the garden, a single flower creating a splash of scarlet among the thorns.

While the ‘Bardou Job’ defied the odds by staying alive on its own for forty years, many plants from the military and penitentiary days didn’t survive. But luckily for the Garden Conservancy, their likeness was captured in photographs. When reconstructing the historical gardens, Fritz’s team used existing photos and their horticultural knowledge to match the look and feel of the original gardens as closely as possible. “I try to avoid anything past 1963 because it doesn’t fit the time period,” she says. But it’s not always easy: “Plants kind of come and go out of favor, and if no one keeps growing those old varieties, they’re lost.”

. . .

On the day of my visit, the volunteer gardeners are planting Carex praegracilis, a grass-like sedge, alongside a walking path on the west side of the island, downhill from the former prisoners’ recreation yard. It’s an area with a gorgeous view of the San Francisco skyline: on a clear day, Beard tells me, inmates could smell the chocolate from Ghirardelli Square. For the prisoners at Alcatraz, the view may have been more maddening than anything, the bustling city simultaneously so close and so out of reach.

The new ground cover replaces a lawn that had dried out during recent drought years. As overseer of the historical gardens, Fritz must occasionally make decisions to incorporate new species that have a better chance of survival in the future, even if they’re not historically accurate.

“I’ve seen a lot of changes just in the years that I’ve been here,” she says, noting how the fog isn’t as thick as in the past and how harvested rainwater tends to run out faster in the summer. Luckily, drought-tolerant succulents were already grown in abundance on the island, many of them brought in by Fred Reichel in the 1940s. But even these plants aren’t immune to changes in climate. (The aloes shouldn’t be blooming this early, Fritz says, but more sun and warmer temperatures this year have caused the succulent to flower during the usual off-season.)

Nearby, four stout tanks sit at the base of a succulent-covered hillside. This is part of a water catchment system designed by an East Bay–based firm that uses gravity to collect water from the rooftops and funnel it to a series of underground cisterns dating back to the military days. The water is then filtered and diverted to the island’s irrigation system, with excess stored in the tanks. The system can hold up to 15,000 gallons of water—enough to sustain the island for an entire year, as long as rainfall levels don’t dip too low.

“We’ve made every effort to be sustainable,” says Fritz. Scraps and cuttings are collected for compost, never hauled away. Over on the other side of the island, near the rose garden, she proudly shows me Alcatraz’s award-winning compost, lifting up a tarp to reveal a shoulder-high collection of steaming organic matter, complete with plump, writhing worms.

Affectionately known as “chief composting officer” is volunteer Dick Miner, a former microbiologist who started working the gardens after his retirement. He zealously took on the composting duties. “This was just the next [logical] step for him,” says Fritz. “It really is microbiology doing the magic here.”

. . .

Fritz estimates she has more than forty regulars who tend to the gardens, many of them—like Beard and Howald—coming every week. Howald pays particular attention to a carefully manicured bed along the main road leading to the cell house. “It’s not just the area I steward but the whole island. You start to feel like it’s your own,” she tells me. “It’s become proprietary.”

And while many volunteers may only come once or twice, there have been plenty who have turned to gardening more seriously after their time on the Rock. “I’ve had quite a few people come out here to volunteer and then decide they really like it,” says Fritz. Some started gardening at home, taking courses at City College, or interning with the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy. One focus of the stewardship program is to equip students with workforce development skills, especially those who may not have had the opportunity to graduate and find themselves cut out from jobs. “This is a stepping stone for those people to get into the environmental field, to come in from a different side,” Fritz says.

For the former inmate gardeners, cultivating flower beds and planting seeds provided a unique opportunity, too. Long before it had a name, horticulture therapy found willing patients on Alcatraz. “The hillside provided a refuge from the disturbances of the prison,” inmate gardener Michener wrote later in life, reflecting on his time on the windswept island. “If we are all our own jailers, and prisoners of our traits, then I am grateful for my introduction to the spade and trowel, the seed and the spray can. They have given me a lasting interest in creativity.” ♦

Nikki Collister hails from Southern California but considers herself a San Franciscan at heart. After graduating from UCLA, she moved to the Bay Area, where she’s held various tech-adjacent day jobs while moonlighting as a freelance writer over the past decade. In her spare time, she enjoys blogging about classic rock, learning new roller-skating tricks, and managing an Instagram account for her cat, Special Agent Dale Cooper.

Christina Kent is a figurative oil painter based in San Francisco. She aims to capture beautiful moments of everyday life in the Bay Area through cityscape and landscape painting.