An afternoon with Lyle Tuttle.

by Frankie Harrington

I had the incredible opportunity to meet and interview Lyle Tuttle a few weeks before he passed away. The culmination of our conversation is the article below. Tuttle was warm, generous, witty, and full of life in all of our interactions. I cherish the memory of our afternoon together.

I head north and inland, beyond the bay, past towns with names like Cloverdale and Boonville. It’s an idyllic drive in early spring: meandering green hillsides dotted with vineyards and cattle. My surroundings as I approach Ukiah evoke a fertile, verdant California-past, connected to San Francisco by the 101 and not much else. Entering Ukiah, I navigate a grid of residential streets and pull up to an unassuming white house with baby-blue window trim. A short chain-link fence encloses the yard, overgrown with weeds. I unclasp the metal gate, make my way down the cement path, knock three times on the front door, and hold my breath.

When I first attempted to interview tattoo legend Lyle Tuttle in the late 1970s, it was for a journalism course at San Jose State University. Our punctilious professor kept her manuscript in the freezer of her Santa Cruz cottage in case of fire and awarded “A’s” only to students who managed to get their work published in a magazine or newspaper. So publication was my goal.

In the 1970s, tattoos were still regarded as deviant: the purview of enlisted men, drunks, prostitutes, and prisoners. Tattooing was illegal in New York from 1961 to 1997, and it was on shaky ground in many other states, but not California. I got my first tattoo, a rose on my left thigh, in 1976. The ruby-red flower topped a stem-like scar sprouting from my kneecap, the result of a gruesome car accident. Although I thought my tattoo was practical—a less expensive and more aesthetically pleasing alternative to plastic surgery—tattoos were by no means considered mainstream.

But tattoos were becoming increasing popular. Tattoos were subversive, an expression of ownership over one’s body and choices. The growing popularity of tattoos, especially tattoos on women, signaled a changing political landscape: the rise of the women’s liberation movement. And thus, Lyle Tuttle found himself in the right place at the right time. Tattooing Janis Joplin, Joan Baez, and Cher put Tuttle on the map, and his needle was buzzing. He catapulted to near celebrity status and was inundated with requests for bracelet tattoos, butterflies, hearts, rosebuds, and flowers. Some femme fatales wanted a tattoo on their breast or inside their bikini line. “Just a little treat for the boys,” Janis Joplin reportedly quipped of the tiny heart tattoo Tuttle inked on her breast.

I knew of Tuttle’s reputation as tattoo artist to the stars and his connection to the Women’s Liberation Movement. I was passionate about Women’s Lib and proud of my tattoo, so I felt an affinity for this well-known, egalitarian tattoo artist. If I could interview Tuttle, who had already been featured on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine in 1970 and in Life magazine in 1972, my article was sure to be published.

Eager for a chance to speak with Tuttle, I jumped in my car and drove to his shop at 30 Seventh Street in San Francisco. I climbed the building’s stairs two at a time up to the second-floor entrance. From outside the door, I could hear the monotonous buzzing of the vibrating tattoo needle. But Tuttle wasn’t working that evening. Instead, I interviewed the tattoo artist on shift and paid him to color-in the miniature heart and butterfly tattoos on my shoulder, before making my way back to San Jose.

Forty years later, I’m standing on the front step of Tuttle’s home in Ukiah, holding my breath. A woman answers the door. “You’re here to interview my Dad, right?” she says, inviting me into the house. “He’ll be right back.” I step inside. To my left is a knick-knack cabinet filled with a hodgepodge of collectibles: a petrified piranha from South America, miscellaneous figurines, and wood carvings from countless global travel destinations. On a perch on the front windowsill, a beige cat suns himself. Another cat, calico, pads across the worn living room carpet to rub against my leg. The wall behind the couch is covered in 4×6 photos of Tuttle and his many friends. In some of the photos, his shirt is off, and in others, he’s wearing only a speedo. Except for his hands, feet, and head, he’s fully tatted. The adjacent walls feature original Shawn Barber and Frank Koci oil paintings.

After about five minutes, the front door opens, and Tuttle walks in. He greets me grinning widely, shakes my hand, and pats me on the shoulder. In spite of my nerves, his presence puts me at ease. His warmth makes me feel as though we have a shared history beyond our missed connection forty years ago. We head to Ellie’s Mutt Hut & Vegetarian for lunch, a rustic white-brick and wood-shackled café off of State Street.

Lunchtime at Ellie’s is busy. The hostess seats us at the only open table, which still has dirty dishes and napkins, the evidence of previous diners. I order a vegetarian sandwich and Tuttle orders a BLT with a side of butternut squash soup in a coffee cup. “It saves a lot of work,” he says about the drinkable, no-spoon soup. Tuttle pulls up his sleeve to reveal the tiny tattooed penguins on his arm, from his 2014 bucket list trip to Antarctica.

“Tattoos are travel badges, stickers on your luggage, signposts of your life that show where you’ve been.”

Tuttle, I learned, has tattooed, and been tattooed, on all seven continents. When I ask Lyle to show me some of his other tattoos, he jokes that “you show tattoos at bars, not at quasi-vegetarian restaurants.” He adds that he got his tattooed armbands, anklebands, and neckband first and then filled in the rest.

“Libras have to have everything balanced.”

The crowded restaurant is noisy and abuzz with conversation. Tuttle fiddles with his hearing aid and cups his ear while I repeat some of my questions. Partway through our lunch, an older couple walks in. Tuttle waves and they politely reciprocate before finding the hostess. I wonder what this elderly twosome thinks of the inked skin peeking out of Tuttle’s long-sleeve shirt.

At the end of the meal, the waitress places the bill face down on the table. Tuttle reaches for it, but I get there first. He graciously accepts. “Now I can show you all the good stuff back at the house,” he says as we walk back to the car. I open the door for him to get into the passenger’s seat. He comments: “Aren’t I supposed to do that for you?”

Our conversation back at the house weaves through decades of San Francisco and tattoo history, as Tuttle tells me his stories. Born in Iowa and raised in Ukiah, California, the loquacious “Lyle the Legend” is a walking, talking, tattoo history book. In 1939, when Tuttle and his parents went to the Golden Gate International Exposition at Treasure Island, he looked across the bay and saw the tall buildings and bright lights of San Francisco, and he fell in love with the city by the bay. “I knew that there was some chicanery going on over there that wouldn’t be going on in Boonville where we were living,” Tuttle says.

Tuttle’s first exposure to tattoos was in 1941 when he saw the sailors and marines coming back from Pearl Harbor. He was ten years old. As the soldiers returned from their service, “they’d have a little tattoo here, a little tattoo there,” Tuttle says.

“At that young age, you think that war is a great adventure and that it’s romantic. I was in my testosterone development at that time and I really thought those tattoos were hot stuff.”

Tuttle’s parents finally let him take the bus to San Francisco on his own when he was fourteen years old. He went into the city not thinking of getting a tattoo, but he wound up stumbling across a shop near the greyhound bus station. He couldn’t resist. He got his very first tattoo: a heart with “Mother” written across it, on his arm. When he got home, “It was like I’d been stung by the devil.” The kids in high school liked it, but the parents did not. In response, Tuttle’s mom used “mom psychology.”

“She figured if she didn’t give me hell, I wouldn’t do it again.”

Sorry, mom.

Coincidentally, Tuttle’s original tattoo shop was located across the alley from the spot on Seventh Street where his own tattoo story began. He worked there for twenty-nine-and-a-half years. The Lyle Tuttle Tattoo Studio became the first tattoo museum in the US and one of the most photographed tattoo shops in the world.

“One of my kids once said that my tattoo shop looked like a laundromat with no machines because it was like a doctor’s office inside—squeaky clean,” Tuttle says. One evening, a young woman came into Tuttle’s studio requesting a tattoo of a ring on her finger with some curlicues. She was looking around the bare shop and she said, “You know, this is the Age of Aquarius.” He humored her. “What do you think we should do in the Age of Aquarius?” She said, “I think we should make it look like a Victorian whore house.” Tuttle replied, “Well, I missed that era.” He later put up flocked wallpaper and décor that jazzed the place up, but on this evening, he kept talking to the young woman while people streamed in and out of the shop. She said, “You know, there’s a story here.” She confessed that she was a writer for Rolling Stone. “The next thing you know, a photographer arrived. She wrote the story, and bingo, I was on the cover of Rolling Stone Magazine.” The reporter happened to have had a roommate in college that was a writer for Life Magazine. “Next thing you know, I was in Life Magazine!”

“Little high-school dropout from Ukiah, California is on the cover of Rolling Stone and in Life Magazine! I called this the ‘stairway to heaven.’ Just one step at a time.”

Tuttle says, “I’m the world’s worst business man. If other people had had the opportunities I’ve had and the name recognition, they would have done much better.” He continues, “The best advice I ever took was my own—work hard, do the best you can, save money, and buy real estate.”

Whereas some tattoo artists avoided the press, and critics, by hiding out on dank, dark streets, Tuttle says, “I was media-friendly.” Everyone wanted to interview him. “I figured that if they were going to put me out of business, they were going to know who they put out of business!” He continues, “It was a friendly period, and I’m just friendly, period!”

Besides gracing the cover of Rolling Stone magazine and the pages of Life magazine in the 70s, he was photographed by two of the most renowned photographers of all time—Annie Leibovitz and Imogen Cunningham. While at his Hollywood tattoo shop, Leibovitz called Tuttle to ask him if he would “pose for her for a picture and $1200.” About this call, Tuttle jokes to me, “Heck, I’d do a Preparation H ad for enough money!” Leibovitz flew from San Francisco to Los Angeles to take the picture. Tuttle describes the photoshoot: “They put a graphic on a backdrop paper, cut a hole out where my head was so I had a halo. I had long hair at the time, and they outlined me in Christmas lights.” Tuttle’s tattooed body was nude except for a strategically-placed Christmas star. This famous picture was Rolling Stone’s 1972 Christmas card.

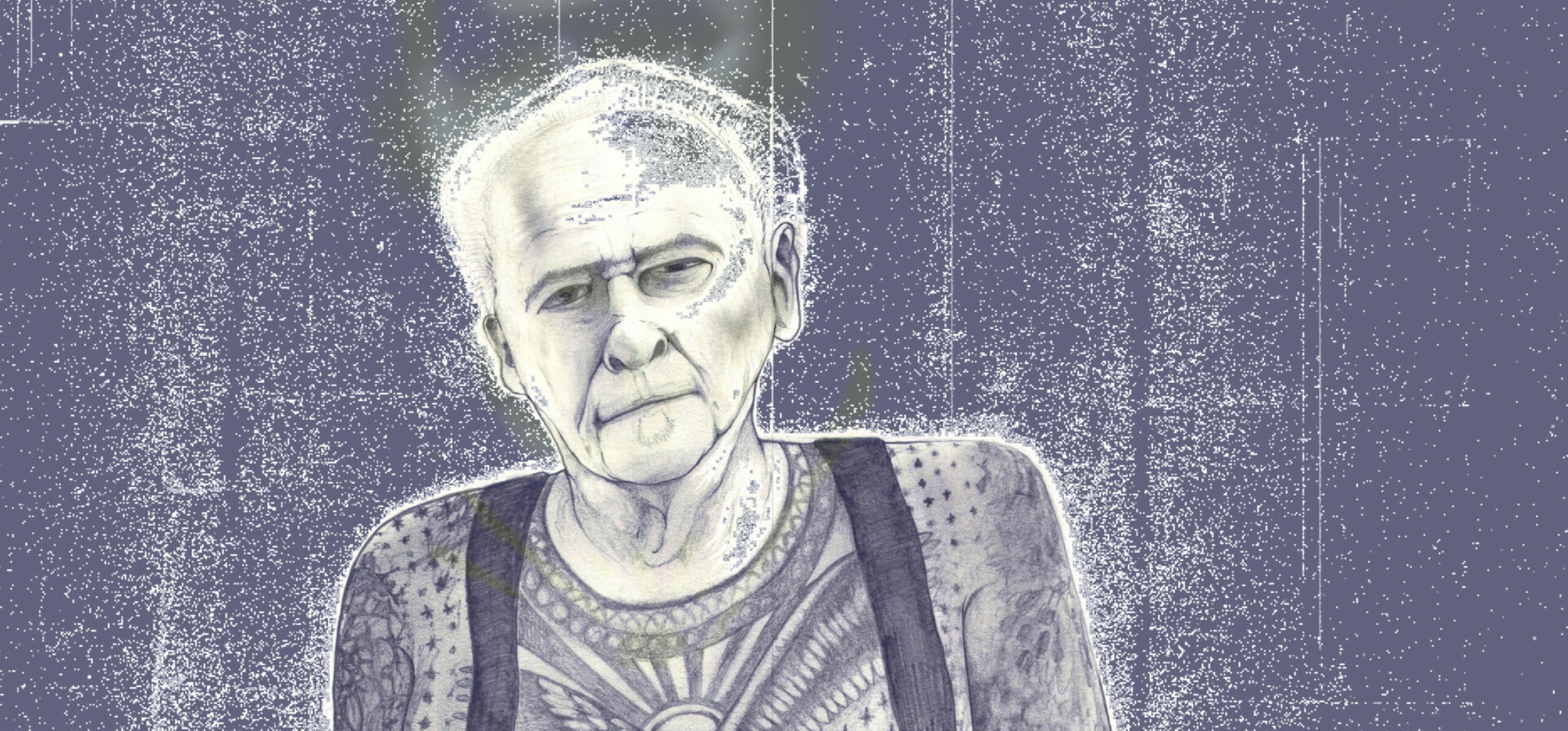

In 1976, Imogen Cunningham, famous for her intimate portraits, photographed Tuttle’s tattooed bodysuit while he sat on a couch with his legs crossed. His facial expression in this photo is open and warm. He gazes off beyond the camera and offers a soft, welcoming smile. His body, from neck, to wrist, to ankle, is covered in tattoos.

I ask Tuttle which part of the body is the most painful to get tattooed. His response is quick: “The one that you’re getting right then!”

“Tattoos are neither excruciating nor entertaining. They’re right in-between.”

Tuttle tells me he’s covered up a lot of scars. He once put a rocket on top of the plume of a client whose chest had been opened up. When I ask Tuttle if he’s ever tattooed animals, his eyes light up, and he says, “I have!” He shows me a picture of Chadwick, his beloved English Bull Terrier dog. Like Tuttle’s first tattoo, Chadwick has a heart with “Mother” on his inner leg. “If you look at the website, ‘What happened in tattoo history on this day,’ it says, ‘On Nov 10, 1967, Chadwick was born.’” Tuttle continues, “One of the reasons I tattooed him was, well, he needed a tattoo. He was my buddy.” Chadwick’s obituary was published in Rolling Stone Magazine.

Tuttle endeavored to make tattooing, and tattoos, worthy of respect and admiration. He helped bring authenticity to the art of tattooing. Tuttle says that he was once classified as a pop artist. He was dubbed the “Frisco Flyer,” for his speed and efficiency. He built a tattoo machine to commemorate this nickname, with wings and an eagle’s head.

After the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, the Seventh Street tattoo shop was yellow-tagged as uninhabitable. The Lyle Tuttle Tattoo Studio and Museum moved to the North Beach location at 841 Columbus Avenue, where it still stands today. It is marked with a neon sign of his signature.

One of Tuttle’s proudest achievements was the “Lyle Tuttle: 70 Years in Tattooing Retrospective Exhibit” at the Palace of Fine Arts in September 2018. The exhibit displayed Tuttle’s tattoo art collection, encompassing seven decades of his work. Many world famous tattoo artists and photographers attended to celebrate Lyle the Legend. Attendees lined up for tattoos of Tuttle’s signature, the only art he was willing to ink in the later years of his retirement.

Dr. Fukushi, a pathologist at the Medical Pathology Museum at Tokyo University, was also in attendance. Dr. Fukushi removes full body tattooed human skin off of donated bodies to preserve the skin. Tuttle was measured by the doctor to donate his bodysuit to the doctor’s institute in Japan where it would be stretched and stored in a glass case for viewing. Tuttle later changed his mind.

According to Tuttle, as tattooing became mainstream, it went from a compulsion to a fad. Tuttle says that people have gone crazy getting tattoos for the last ten years. “But, how long do those fads and trends last?” he asks. “Tattooing became more and more popular as time wore on, but it’s going to fall on hard times soon,” he says. Tuttle’s advice? “Don’t get one.” But, Tuttle readily admits that this advice is bad PR for him.

Five hours, a few photos, and a book signing later, Tuttle leads me to the door of his house, a tequila grapefruit in hand. As we walk down the front steps, he raises his glass, squints into the golden light of early evening, and says, “Whatever you do with your article, make me look like a gentleman. That’s all I ask.” Tuttle passed away peacefully at his home in Ukiah on March 25, 2019 at the age of 87, exactly one month and one week after my interview with him. ♦

Frankie Harrington is a regular contributor to the magazine. She likes tequila grapefruits and getting caught in the sun, and she’s also into yoga.