Short film by Guy Wilkinson.

The thump of bass hit my chest as I drew closer. I smelled something cooking on a grill and saw a dozen people grouped around a car with paintwork so intricate, it was more art installation than mere vehicle. Further on through the crowd, a procession of cars with sound systems blaring bounced toward me single-file down Mission Street, the car in front jacking up obliquely on two wheels to a chorus of wolf whistles. Parked at 45-degree angles, hundreds more lowriders, each seemingly more flamboyant than the next, flanked either side of Mission. Drawn to the energy of the crowd and the paintwork resplendent in the Saturday afternoon sun, I began to photograph the scene. Across several months in early 2022, I returned with my camera again and again, inspired by the artistry and joy of the lowriding events I witnessed.

—Guy Wilkinson

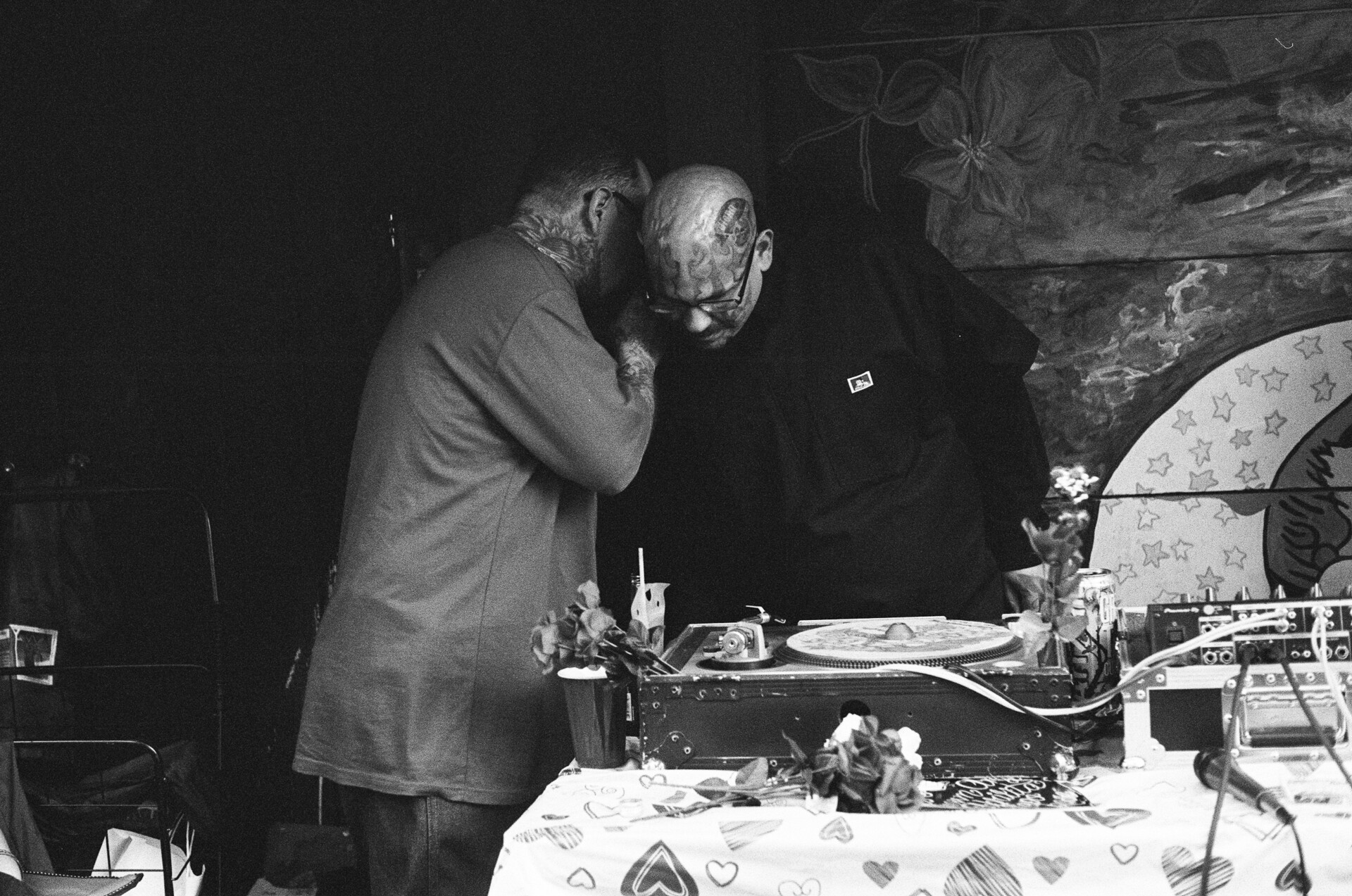

A deeply entrenched source of cultural pride within the Latino community, lowrider events are about far more than posturing, bling, and custom-built rims. Photographed on Mission Streeet with a Pentax K1000 with Tri-X 400 film.

A deeply entrenched source of cultural pride within the Latino community, lowrider events are about far more than posturing, bling, and custom-built rims. Photographed on Mission Streeet with a Pentax K1000 with Tri-X 400 film.

Editor’s Note: At events throughout the year, San Francisco’s lowriding community takes to the streets in celebration and in protest. We spoke with Roberto Hernandez, founder of the San Francisco Lowrider Council, about the storied history of lowriding in San Francisco and the significance this mode of expression holds for his community.

. . .

“It’s an art form. I call it the art of lowriding. It’s a Latino art form, it’s something we invented,” Hernandez said. “We were stereotyped as these bad boys, when in reality we worked four jobs just to be able to afford a new set of rims and hydraulics and all the accessories that go into putting a car together.”

Now a Mission mainstay, and a deeply entrenched source of cultural pride within the Latino community, lowrider events are about far more than posturing, bling, and custom-built rims.

Back in the early 1980s, Hernandez founded the Lowrider Council in response to repeated police harassment of Latino men, especially those driving lowrider cars. After a successful legal injunction, the right to cruise on Mission Street and other designated parts of the city was solidified for generations to come.

When asked what he wished people understood about the movement, Hernandez said, “We had to struggle for the right to be able to lowride. Police used to shut down the streets. When you look at the lowriding movement, we didn’t file suit because of money, it was never about money. It was about our civil rights and having the right to cruise. White kids used to race for pink slips [ownership] down the Great Highway, and the police didn’t bother them. What’s more dangerous, low and slow, or racing? It was important to be vocal and stand up for what we believed in.”

The San Francisco Lowrider Council has thrived since its inception, using slick cars, clothes, and bicycles as a means to showcase Latino culture, bring together the community, and advocate for numerous social justice causes, such as the United Farm Workers, immigration reform, police reform, and Free the Children.

“Especially more recently, the San Francisco Lowrider Council has been fighting the gentrification of the Mission,” Hernandez said. “We are asked to protest and we show up deep, with lowriders. Seeing us can give someone a lot of joy and hope, and make an impact.”

Hernandez also leads Mission Food Hub, a nonprofit food bank, and is the executive producer of Carnaval San Francisco. “The first Carnaval, forty-four years ago, we had five cars in the parade. Now there are a hundred cars leading the parade,” Hernandez said. “Looking at lowriders today, it’s amazing. It’s become a mainstream art.”

“The ’64 Chevys are like the BMWs of lowriding, that’s why I have a ragtop and a hardtop,” said Hernandez. “I got my first ’64 Chevy from my neighbor who retired. These were Sunday-drive cars. My neighbor’s ’64 Impala was yellow with a black interior. I have five cars. I put time, money, and love into my cars.”

“We’ve been invited to be in the Warriors Championship Parade, the SF Giants Championship Parade,” said Hernandez. “We’re rolling deep. We’ve got nothing but love. Rolling down the street, I feel like a kid. We bring a lot of joy and happiness to people.”

“Music is big. We put a lot of money into our sound systems,” said Hernandez. “We listen to a lot of classic oldies, Smokey Robinson, a mix of Afro-Latino, soul music, salsa from back in the day. And food. We always have barbecue, carne asada. Someone brings tamales. The food is part of the culture. Food and music and conversation.”

“In the process of creating your machine, you draw creativity from the juices in your mind, your heart, what you love. The spirit that you find within yourself creates this amazing machine that dances. What I create on a particular lowrider nobody else will do, you’ll never see somebody else do,” Hernandez said.

“It’s about pride. Be proud,” Hernandez said. “This is a Latino cultural art, an asset. I tell [the next generation] to enjoy it. When we go cruisin’, just smile. It’s about joy.”

“The elders of lowriding, a lot are retired now,” Hernandez said. “A lot of them spend more time buying details or repainting their cars. They didn’t used to have time, but now they have time. Somebody might buy a car and it’s a project car. I have a project car I’ve been working on for seven years.” ♦

Guy Wilkinson spent a decade working as a travel writer in Australia before realizing a career extolling the merits of spa weekends in the Daylesford countryside wasn’t his true calling. Originally from the UK, he traded London smog for San Francisco fog and focuses on portraying subcultures and street life in short films, documentaries, and photography. To see more of his work, check out his linktree.