Remembering Chinatown’s most well-known forgotten photographer.

by Charles Russo

A few years back, I drove over to Berkeley in search of a single photograph.

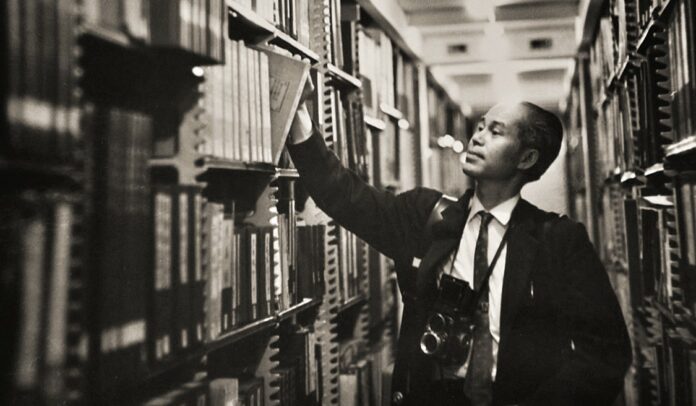

If my research was right, the image was in the Kem Lee photo archive at the University of California, Berkeley, Ethnic Studies Library. The collection contains over 200,000 images that Kem took during his half-century-long career photographing San Francisco’s Chinatown. Yet Kem, his images, the archive . . . it was all new to me, despite my background in both photography and local history.

Actually, it was Bruce Lee who led me to Kem Lee, so it was the world’s most famous martial artist who led me to Chinatown’s most sorely forgotten photographer. While writing my book about Bruce Lee’s early years amid the pioneering martial arts scene in the Bay Area, I inevitably came upon 1029 Grant Avenue: the Sung Sing Theatre circa August 1964. Bruce had accompanied A-list Hong Kong starlet Diana Chang Chung-Wen — aka the Mandarin Marilyn Monroe — for a packed-to-the-rafters revue promoting her latest film. She sang a few numbers, they danced the Hong Kong cha-cha together on stage, and then during intermission Bruce gave a kung fu demonstration that broadcast his modern martial arts worldview to a mostly unreceptive crowd.

It was an awesome story from the heart of Chinatown yet one that existed in a hazy limbo between obscurity and urban mythology. Eager to excavate it further, I figured that Diana’s visit had been high-profile enough that there had to be photographs of it . . . somewhere.

A roundabout Google search eventually led me to Kem Lee’s archive at UC Berkeley. So I requested the appropriate files, made the trip, and indeed, there inside a folder within an archive box was a photograph Kem had taken with his medium-format Rolleiflex of Bruce and Diana looking cool and glamorous the night of the Sung Sing event. It was exactly what I was searching for.

Successful in my foraging, I took a moment to explore the remaining photos. There were urban landscapes of Grant Avenue from 1959, portraits of Forbidden City nightclub dancers, color shots from one of JFK’s visits to San Francisco, and candid pics of Soong Mei-ling (first lady of the Republic of China) during her celebrated tour of the U.S. in 1943. Every folder contained numerous photographs like these, and each box contained dozens of folders. Looking through the images, I quickly realized that Kem’s body of work comprised a vast and historically vital visual record of the Chinese American community. Suddenly, that single image of Bruce and Diana seemed like one gemstone amid a treasure trove of stories. After all, I was only perusing four boxes of his imagery. The archive contained 169.

It all left me to wonder: how had this expansive visual chronicle that Kem Lee created for San Francisco fallen into obscurity?

. . .

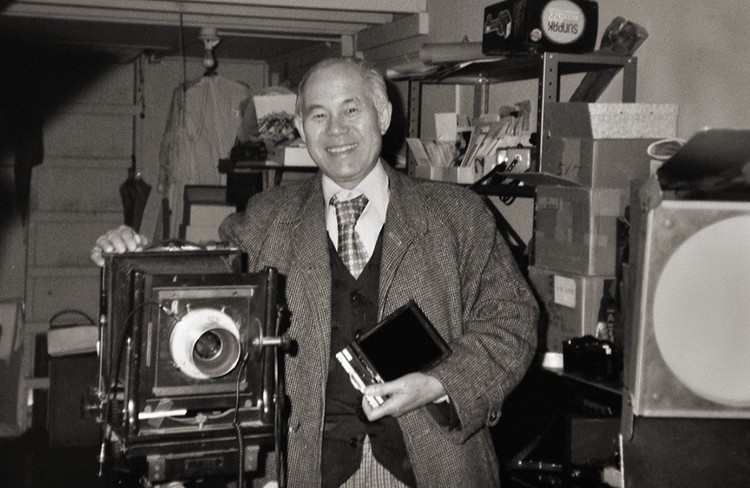

A 1979 San Francisco Examiner article characterized Kem Lee (1910–1986) as “the Dean of Chinatown photographers” — an apt title for an accomplished lensman.

For five decades — from his earliest beginnings with the medium of photography in the late 1920s through his official retirement in 1978 — Lee chronicled nearly every facet of life in Chinatown. He photographed weddings, birthdays, graduations, funerals, parades, festivals, and countless other social functions throughout the neighborhood. Kem shot the big-name celebrities who came through town, including actors such as Cary Grant and Nancy Kwan, as well as musicians like Duke Ellington. He also immortalized visits by at least eight U.S. presidents, from Truman to Reagan (though, to be accurate, Ron was still the governor at the time).

Over the years, Kem captured the changing physical landscape of Chinatown and applied a documentary-style aesthetic to the neighborhood’s businesses and shopkeepers. He produced a small mountain of passport photos (“to pay the bills,” as his son Colin recalls). An artist at heart, he also created a wide range of abstract imagery inspired by the shadows, shapes, and reflections of the Chinatown cityscape.

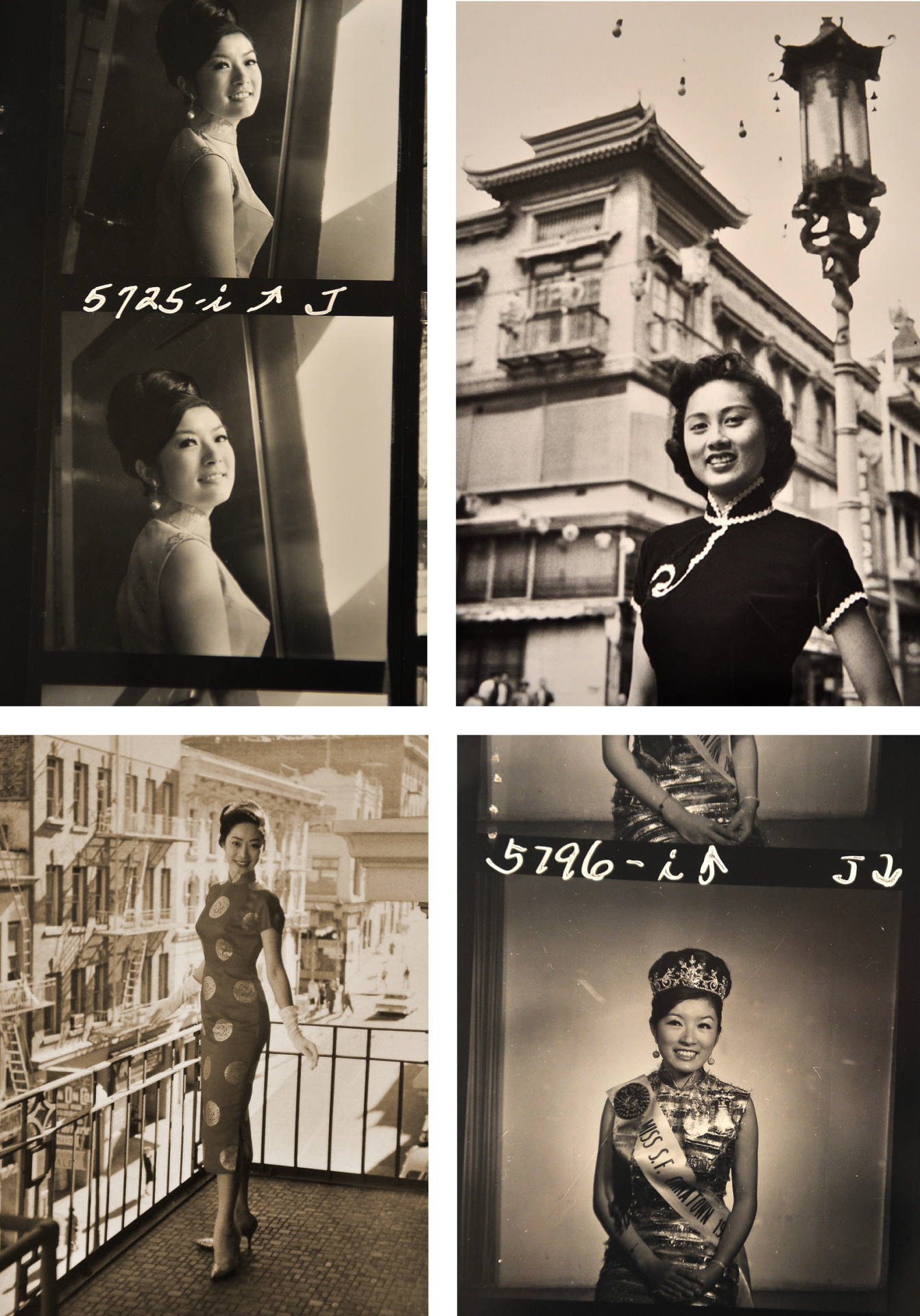

Most notably, perhaps, Kem was the official photographer for the Miss Chinatown USA Pageant, dating back to its earliest incarnation in 1948 and throughout its evolution into one of the neighborhood’s premier annual events. Kem took great pride in that role, displaying his portraits of the winners inside his studio on Clay Street and continuing to cover the competition into the 1980s, well after his retirement.

“As a kid, I was a big fan of the Miss Chinatown pageant,” recalls filmmaker and author Arthur Dong. “It was the big glamour event in the neighborhood for everybody who lived there, and I can still see Kem’s photographs in my head now, because we closely followed those images every year.”

Formally trained as a painter, Kem had turned to a career in photography only after his initial efforts at a graphic design business faltered. Gregarious and personable, he was well suited to being a neighborhood photographer. When he married well-known local artist and poet Nanying Stella Wong, the two formed a sort of power couple when it came to the cultural currents of the community, granting Kem additional access to Chinatown life.

And while there were other noteworthy photographers working in the neighborhood over the years — Ken Cathcart, Tom Lee, Charles Wong — Kem was unique, not just for his tenure but also for his large output and industrious approach. Buzzing around the community throughout the day, Kem would shoot an event, rush back to his studio to develop his photographs, and then dash back out to submit them free of charge to the local Chinese-language newspapers (such as China Times or Chinese Pacific Weekly), who didn’t have a budget for photographers. “All I got for it was a byline,” he told the Examiner, “but it has helped build up my trade.”

This informal arrangement provided accurate imagery and overdue exposure for a severely underrepresented population within the city. As Stanford historian Gordon H. Chang explained in his book Asian American Art, “Until Lee’s images of San Francisco’s Chinatown appeared in papers, few people in Chinatown had seen positive images of their community in print.”

All told, Kem was in many ways the neighborhood’s visual-art equivalent of celebrated San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen: regularly out and about recording the rhythms of the city and the residents who inhabited it. Whereas Caen contributed words via a Royal typewriter, Kem crafted images using a Rolleiflex camera. Yet Kem lacked the larger (and better-paid) platform that Caen had with the Chronicle, instead making his living by way of an endlessly underfunded and often unsung hustle.

. . .

To say that Kem Lee is forgotten is not quite accurate. Ask anyone who lived in Chinatown during his tenure and it’s a sure bet they’ll know him by name. For local residents, Kem often seemed like he was everywhere in the neighborhood at all times, making him a highly recognizable figure over the years. (“He’d walk down the street and get stopped constantly to have conversations,” recalls Colin Lee.) In this regard, it’s not so much that Kem is forgotten but that his work and his legacy are simply not celebrated within San Francisco, despite his decades-long dedication to it.

A vivid example of Kem’s posthumous obscurity can be found in today’s Chinatown, on a half-block stretch of Clay Street between Portsmouth Square and Grant Avenue. On the north side is Kem’s former studio at 768 Clay (now occupied by a jewelry store). Nothing there commemorates Kem, or even acknowledges his once-daily presence. Yet up until recently, directly across the street was a mural paying homage to the Arnold Genthe photo The Street of the Gamblers. Genthe’s image portrays male residents of Chinatown traversing Ross Alley in 1898. You would likely recognize the photograph: it’s in the permanent collection of the SF MOMA, and it regularly surfaces in documentaries and history books about SF’s Chinatown.

Genthe was a self-taught German-born photographer who immigrated to San Francisco in 1895 and gave considerable attention to capturing street scenes around Chinatown. His photographs have merit, particularly in that they comprise the only visual record of the neighborhood prior to the 1906 earthquake, but they’re clearly an outsider’s perspective. As Stanford’s Chang put it, “Genthe’s images often say more about his own conceptions than they do about Chinatown and its people.”

Back when I studied history, art history, and photojournalism at SF State, Genthe’s photographs surfaced in many of my classes, on multiple occasions. Kem’s never did, ever. This is especially confounding when considering that one of the greatest attributes of Kem’s legacy as a photographer was his ability to capture the true essence of the place that he documented.

“Kem Lee’s photography represents the perspective of someone with deep roots and connections in the Chinatown community,” says UC Berkeley Ethnic Studies Librarian Sine Hwang Jensen. “Unlike Genthe, who often photographed people in Chinatown candidly and whose patrons were majority non-Chinese, Kem Lee took treasured portraits of community members and documented the vibrant life of the community for the community.”

And yet, Arnold Genthe is practically a household name when it comes to historical photographs pertaining to San Francisco’s Chinatown, while Kem is — at best — relegated to the footnotes in the backs of books and the small-font scroll at the end of documentary credits.

In this context, Kem Lee is not merely one noteworthy photographer who somehow slipped through the cracks of popular memory but a case study that raises deeper questions about representation, the historical record, and who gets to participate in it.

. . .

Despite a lack of gallery exhibits and coffee-table books (or, for that matter, city murals) promoting Kem’s work, his archive still gets regular traffic and interest. As Jensen pointed out, Kem’s work is frequently consulted by a wide range of researchers (“genealogists, film directors, writers, authors, students”) from around the world. Often, the imagery resonates much closer to home.

“It’s a particularly special feeling when community members see relatives or friends in the archives as well,” Jensen says. “To see themselves reflected in the archives reinforces the fact that their history and community is important and deserves historical preservation.”

In this sense, Kem Lee was — much like Herb Caen, and even Arnold Genthe — a steward of the city’s legacy, and he should be afforded the same attention and reverence.

“His work is vitally important,” says filmmaker Dong, “and we need to see it.” ♦

Charles Russo is a local journalist and the editor of The Six Fifty, an online magazine covering Silicon Valley and the SF Peninsula. He is the author of Striking Distance: Bruce Lee and the Dawn of Martial Arts in America, which explores Lee’s time in the Bay Area during the 1960s.