Reminiscences of an intrepid bicycle courier.

For a couple of years in the mid-1980s I was a private bicycle delivery person for ARCH Drafting Supply in San Francisco. I’d been a bike courier for a year or two prior at Aero Delivery, but the requirements for ARCH were a little more specific. The standard messenger transpo at the time was a mountain bike with a large, heavy wire basket bolted to the handlebars. This was fine for the usual courier fare of envelopes and small boxes (though I did once have a birthday cake bounce out and under the wheels of a Muni bus). Materials from ARCH, however, were of various sizes and shapes, and some were more delicate than your average parcel, requiring extra bungees, cardboard reinforcements, and the like. Still, I was limited by what I could fit in the basket or occasionally balance on top of it, and as a result some days I had less work than I was used to. Although I was getting paid by the hour by one of the best bosses ever, it pained me to see so many flats of art paper and board, which were among the most frequent orders, go out daily by van at a much higher cost.

On one particularly slow afternoon I had a stroke of smartness and set about inventing something to carry those big flats on top of my basket. I grabbed a giant piece of one-inch-thick gator board and cutting materials, and set to work. (Gator board, for those unfamiliar, is a much more rigid form of foam-core presentation board with a ceramic coating instead of paper.) First I cut two rectangles, each slightly larger than the common 20 x 30″ and 30 x 40″ sizes of board and paper. Next, and a little more challenging, I carved out two one-inch-square holes close to one of the longer edges of each board, for straps to attach to the basket. Then came the fun part. I wrapped each of those boards with duct tape, meticulously covering every edge, the insides of those neat square holes, and every inch of surface twice, making them even sturdier and pretty darn waterproof (and lovely and silver. Duct tape is always in fashion in my book.) Finally I got a friend with a sewing machine to stitch some badass black side-release buckles to strips of nylon strap after having threaded them through the holes in the board, so that nobody but nobody could pull them out save by cutting them. Yes, this all took more than that one afternoon, but when it was finished I could slap either board on the basket, buckle it down zippity-zap, and voilà!—the ARCH Messenger was born.

The gods love a jury-rig.

This invention worked quite well, allowing me to carry a good deal more than I had before. Beyond the frequent orders of paper and board, which were now a snap to deliver in perfect condition, I had a second surface on which to stack parcels up to a foot or two high at times, with appropriate use of bungees, of course. The boards were light and oh so sturdy, I could remove or switch them out in a flash as needed, and they actually improved the stability and balance of a lot of loads. After a time, I became confident with them, and could easily glide through traffic and even between lanes of stopped cars with a full load. I’m certainly a klutz and a dunce about some things, but I have terrific spatial acuity (even more so back then) and could guide those flats often without slowing within an inch of car mirrors on either side, never hitting a one. Not only did I save the store cash on a lot of pricey van runs (sorry, Quicksilver), I was able to schlep those parcels to their destinations easy as pie. Everyone was happy.

Some months later, when my expertise with the system had become second nature, I popped into the store after a run at 4:30 one afternoon to find not much happening. There was only one van delivery to go out and nada coming in, so the manager told me I could go home for the day. But it was a gorgeous sunny summer afternoon, which meant that we had an hour or two before the fog began pouring in from the west, and I was in my mid-twenties, i.e., brimming with vim and more up for a challenge than a chill. I glanced at the waiting package leaning against the wall, which was huge—four by eight feet of gator board in a stack about six inches thick—professionally wrapped, and ready to go to a firm just a couple of blocks away. I was always looking for ways to test my skill with my delivery system, and here was a big chance to do so.

“Did you call the van for that yet?” I asked the manager.

“Just about to.”

“Let me take it,” I piped.

“How are you going to carry that thing?”

“I’ll take it on the bike.”

“No, you won’t.”

“I can totally do it.”

I knew I could do it, though the manager most definitely did not. But I did have some charm back in those days, and knew how to jump around enthusiastically and look cute. I also said that if the materials got damaged I’d pay for them and the van. I was an idiot. Amazingly, the manager agreed, and the experiment began.

The employees all pitched in to help me load the package onto the bike. This was a major bungee-and-cardboard job, needing every cord and strap I had, and I still needed to tie the base board to the basket to keep it from flapping. The manager was right—this thing was too heavy and awkward to carry far, let alone easily keep in balance. Somehow we managed to get the behemoth parcel secured, centered, and as level as possible, with three feet of it hanging off the front of the basket and, well, close to four feet on either side. The bike was seriously front-heavy, wobbly, and hard to even push, but I was determined. ARCH was located at the time on Jackson Street a few buildings west of Sansome, on the northern edge of the Financial District and the southeast corner of Jackson Square. All I needed to do was get the bike two blocks east on Jackson past Sansome and Battery to Front Street, then half a block to the left. A cakewalk, a hop, skip, and a jump, and an increasingly intimidating endeavor. At least the route was flat, as were all the streets to the south and east, the Financial District being mostly built on landfill. I was good to go, and as I pushed the bike tentatively down the sidewalk to the end of the block, my workmates cheered me on and wished me luck. They were all good folks, and most likely expected me to succeed swimmingly rather than crash and burn. I was a little less sure.

I hopped on the bike a bit unsteadily, and when the light turned green I pumped it hard into the intersection. That’s where I hit my first bit of trouble. It was about five o’clock by this point, and the evening winds were already beginning. At this spot there was a good breeze pouring off the hill to the north, competing with a much stronger one coming down the steeper slopes of Nob Hill to the west. You see, there was one important thing that I forgot, that I didn’t factor in, that I didn’t think about. That was the fact that on the other side of Sansome Street the buildings were much taller than those around ARCH, more than fifteen floors compared to the usual two or three stories of Jackson Square. As a result the wind was sucked down that block with a great deal more force than anywhere else around, especially in the breezy afternoon. Every messenger knew this; I just hadn’t realized that this load was large enough to be impacted by meteorological conditions. I caught on fast, though, as I met the winds churning in the intersection that almost flipped me over like a leaf. Somehow I managed to keep it steady(ish) and make it across without toppling. Then I hit the wind tunnel.

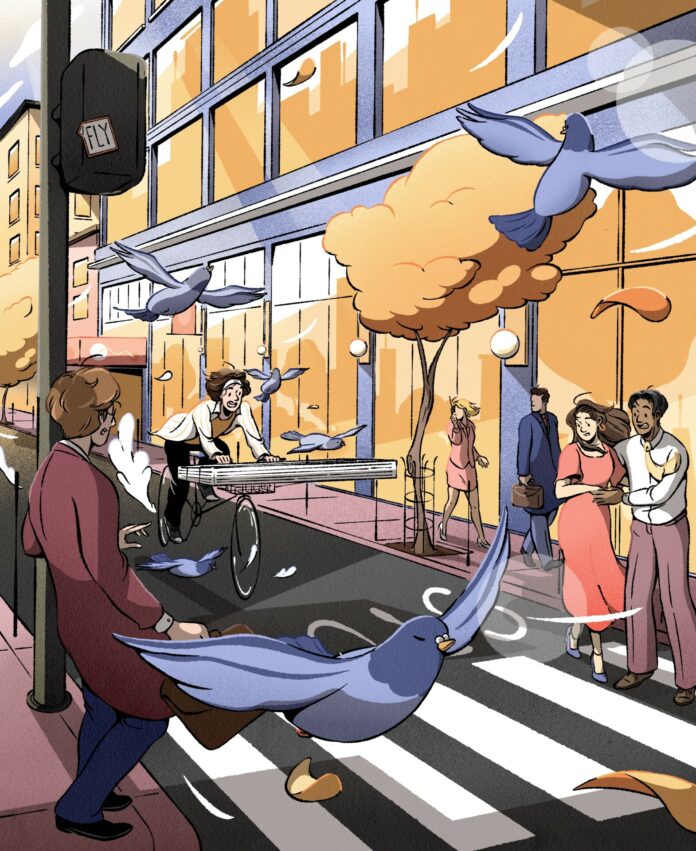

The bike took off like a rocket, or really more like a glider in a gale. The wind hit that sturdy eight-foot board and pushed. I have no idea how fast I was going, but I shot down that entire block, where fortunately there was no traffic at the time, in no more than several seconds, at maybe 30 miles per hour. This all happened very fast. I was breathless, but as long as I kept that front wheel straight, I would be okay. Then I realized two things almost at once. The first was that the board, the wing, was no longer tilting downward but was level and noticeably higher than it had been, and the front tire was no longer touching the ground. The parcel had in fact become a wing, and I had essentially turned my bicycle into a light aircraft. I assume the rear wheel was on the ground, but I wasn’t able to look, and for all practical purposes I was flying. The second thing I noticed was that I was coming up on the intersection of Jackson and Battery at quite a clip. Seems like Luck, that Patron Saint of Wild Children, was with me, as the traffic light was in my favor. Thing is, it was the very start of rush hour, of go-home hour, and the intersection was filled with people doing just that, a few of whom were milling across Jackson Street against the light, having noticed no cars or trucks approaching. They were correct in that, though there was a light aircraft made of titanium and gator board bearing down on them. I had no way to slow or stop without crashing badly; I wasn’t even sure I could turn the wing if I had to. My instinct took over and I let out a screech worthy of a pterodactyl that stopped everyone in their tracks. Those few in my path dove to the side and I flew through triumphantly, exhilarated and very relieved. I couldn’t help but think that those pedestrians had just seen something that quite possibly no one else had ever seen (except perhaps the Wright brothers) and that they’d be unlikely to forget.

The wind died down and the front wheel touched down and I pumped the brakes lightly till the bike came to a stop at Front Street. I dismounted shakily and walked it the rest of the way. The package arrived undamaged as, miraculously, did I.

Back at ARCH, everyone was thrilled that I had survived, and my coworkers were quite amused with my amateur aeronautics. The manager less so. The owner didn’t find out about it until I showed her a copy of this story a few months ago. “What else didn’t I know?” she asked with a grin. ♦

Richard Loranger is a writer, performer, and visual artist based in Oakland. “The Day I Learned to Fly” is part of a series of his recollections about bike messenger culture in 1980s San Francisco. He still occasionally makes his way over to ARCH Art Supplies, now at the foot of Potrero Hill.

Nien-Ken Alec Lu is a freelance illustrator dwelling in San Francisco with his husband and their plant babies. He has illustrated for many editorial and commercial clients. In his downtime he walks around the city trying new coffee shops and restaurants and immersing himself in SF’s diverse food, film, and art scene.