All I can hear as I’m typing is the clacking of my fingers on the mechanical keyboard you gave me for Hanukkah. It’s the last gift I have from you, unless we count B, but I consider her an inheritance. The keyboard is so loud that I can’t even hear myself think, which is just as well because I fear I’m not making much sense.

Today is my first writing day in a while, and I’m only writing because you would want me to, or at least that’s what everyone kept telling me after the funeral, before I lost my phone, back when I was still engaging with the world. It’s a nice idea, that my big brother would want me to be doing the thing I love most, but I don’t know if I love writing anymore. I certainly don’t love the sound of this keyboard, but I don’t love the silence that ensues when I’m not typing, either.

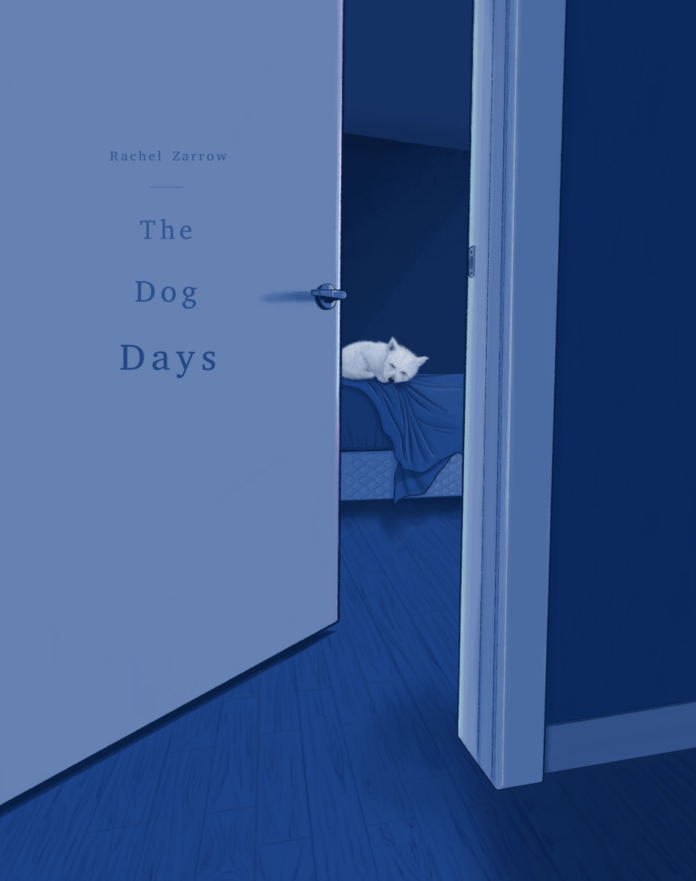

I join B on the blue velvet sofa, where she is curled into the shape of her namesake, a bialy. Her wiry white fur is everywhere. Whoever thought a blue velvet couch was a good idea when you live with a dog was sorely mistaken. I was sorely mistaken. When I ordered the couch and paid the extra eighty dollars for white-glove assembly, you looked at me like we weren’t related, like I wasn’t your sister but only your roommate, and a Craigslist roommate at that. You thought the couch was another one of the trappings of an upwardly mobile millennial striving for an Instagram aesthetic—something you used as a punch line in a stand-up routine—and you weren’t wrong.

Critiques of taste and consumerism aside, at least B likes the sofa. She opens her eyes and closes them again, thrusting her nose further into the space under her tail that can really only be described as her asshole. My presence is less exciting to your dog than her own butt. My dog, I correct myself, eyeing this scruffy former street dog with bat ears that probably account for half of her ten pounds. B’s my dog now.

It’s April, and you’ve been gone for a little over a month. For the first few days after the funeral, I pretended you were traveling for work, that I hadn’t just watched the pine box containing my brother’s body get lowered into the earth. Though all my colleagues have been working remotely since the stay-at-home order went into place, I am not. Working, in any sense of the word. When I took my paid two-week sabbatical (thank you, Big Tech), I insinuated that I was finally working on my novel. When I extended my sabbatical without pay, I continued to let everyone think it was for my writing rather than my grieving.

I read what I’ve written aloud: Have you ever spent so much time alone, been silent for such a long time, that you forget the sound of your own voice?

I have no idea if it’s any good, but at the very least it’s true. After so many weeks of silence, I have forgotten what my voice sounds like.

I’m reaching for my mug of coffee, now cold and gloopy with coagulated almond milk, when a voice startles me.

“You’re not alone,” it says.

I spill my coffee all over my shirt as I spin around to find the source. But what I find is B stretching on the back of the sofa—bowing down on her front legs, and then pressing forward to get her back legs, too, one at a time, those piggy little stumps of hers. I approach her, wondering if I need to check myself in to some sort of facility.

“You’re not alone,” she repeats. “You’ve got me.”

Nothing is real, I think, remembering the words I repeated to myself during the first few weeks after you died. And since nothing is real, the only thing that surprises me is B’s voice itself, which isn’t the three-year-old-girl voice I’d always imagined for her but rather a scratchy and cartoonish voice. My recognition of Bialy’s voice is similar to my recognition of my own voice after my long silence; it’s familiar but long forgotten, the sound kaleidoscopic and shifting, something I recognize as though from a dream.

B attempts to hop down from the back of the couch but stumbles, falling onto my lap like a balled-up pair of fuzzy socks. I laugh at her clumsiness, but my laugh sounds hollow and tinny, like an ice cube hitting the bottom of those jewel-toned aluminum cups we begged Mom to buy us at Target one summer. It was the summer we were obsessed with our puppet theater, the same summer we learned the term alfresco and insisted on dining alfresco every day even though it was ninety degrees out. Within minutes of carrying them outside, the cups got too hot to touch, but we didn’t tell Mom because otherwise she’d have never granted another of our requests on a trip to Target and what’s the fun in that?

“You’re right,” I say, refamiliarizing myself with my voice. “I do have you.”

I turn onto my side and pat the spot in front of my crotch. B climbs over me and curls up in my nook, and soon she’s a bialy and I’m her big spoon. And then she’s asleep, and I am too.

. . .

Since securing a grocery delivery slot has become something of a competitive sport, I’ve taken to ordering from Costco so I can get more of everything, enough to last me ten days. They don’t sell my preferred brand of flour, but more is more. I order gallon-sized bags of leathery dried mango and four-packs of sunscreen even though I don’t like dried mango and other than stepping into the backyard to let Bialy relieve herself, I haven’t been outside since I returned from the funeral. I order two dozen eggs that arrive in a sterile plastic tray specifically designed for this purpose—selling eggs at Costco, the only place I know that sells them by the two dozen. I imagine an ocean filled with these plastic egg holders and realize—for the zillionth time—that I am the problem.

I scramble three eggs that I share with B, mixing half of the rubbery yellow bits in with her kibble. I eat my breakfast while standing in front of the pantry, assessing what’s left from my last grocery haul. With all the flour I’ve ordered, I consider baking. I haven’t baked in months, not since our holiday party in December. You were in particularly festive spirits, and I wonder now if you knew it would be your last winter. We’d been living together for two years, and though I don’t think I realized it then, they were the best years of my life. It must be so nice living with your brother, people always said, especially at the parties we used to throw for every occasion—your birthday, my birthday, the holidays, your promotion at your Evil Corporation, my promotion at mine.

I decide against baking because I can’t recall the last time I felt hungry. B, on the other hand, has a bottomless appetite, and she’s licking her empty bowl.

“There’s nothing left, sweetie,” I say, sitting beside her on the floor.

She crawls into my lap and places her front paws on my shoulders, offering me my first hug in over a month. At the funeral I didn’t even hug Mom and Dad. Our masks made it hard to communicate, which was for the best, because every time either of them said something to me, I expected their words to be prickly with blame: Why didn’t you tell us he wasn’t doing well? How could you let this happen? But we hardly spoke. One son in the ground, one daughter remaining, and nobody touched. I stayed at an airport motel.

I don’t realize I’m crying until B starts licking my cheeks, lapping up the tears.

“You’re not alone,” she says again. “You’ve got me, and I’ve got you.”

I burrow my face into her dirty white fur, which smells like corn chips.

She looks up at me. “More breakfast please?” she asks, and I get up from the floor. “Thank you much,” she says, parroting a familiar phrase.

As I’m whisking another egg, I feel a phantom vibration in my back pocket—only my caftan doesn’t have a back pocket, and my phone is still missing. I think of all my voicemails from you that I’ve lost with my phone. I think of the conversations we had a few years ago when you were persuading me to move to San Francisco. I didn’t think I’d end up on the West Coast, but after a few phone calls, you won me over, promising to teach me to surf. Whenever our calls ended, I’d imagine you paddling out into the dark blue of the Pacific in a wet suit, telling me that the water was warm, the way you did when we were kids, jumping into the pool or testing out the bathwater when we were young enough that we still bathed together. You always wanted to protect me.

As I cook another egg for B, I recall an afternoon when I was in the third grade and you were in fifth. We were sitting together after school in the swings in our backyard when you announced that you needed to tell me something. You said I was going to read Bridge to Terabithia in language arts and that I needed to know the ending in advance because it was too sad, and what was the point of having an older brother if he didn’t warn you about things like that?

I wish you’d warned me how your story would end.

. . .

B and I are back on the sofa and I’m rubbing her belly. She tells me she prefers French films because the accents lull her to sleep. She recounts what little she remembers from her time before the shelter, but she refuses to talk about her experience in the shelter.

“It’s okay,” I say. “We don’t have to talk about it.”

Just then, the doorbell rings. B barks and follows me into the hall. I grab my mask, and as soon as I glance at the bare spot above the console where the poster of the Golden Gate Bridge used to hang, I freeze. I think back to that night when I came home to our apartment after identifying your body and saw the poster with new eyes, wondering if you had thought about ending your life every time you walked through the front door. I shut the door to your room, took down the poster, and left it on the curb with a Post-it that said “FREE.” By the next morning, it was gone.

I stretch my mask over my face and open the door to find one of the women from the upstairs flat. “Hey,” she says.

“Hey.”

“Hey,” she says again, this time with more sympathy in her voice, and I can tell she’s just heard about you. “Do you have a minute?”

I nod and follow her down the steps to the sidewalk. I try to remember if she’s Marcia or Marcy, as I always get their names confused. They look alike, too, with long hair that’s beginning to go gray and thick-framed glasses. With her mask on, it’s impossible to tell which of them she is.

“How are you doing?” she asks.

“I’m all right.”

“I’m sorry we didn’t check in sooner. I didn’t hear about your brother until today. Things were so hectic when the kids’ school went online, and I missed the story in the Chronicle.”

“It’s fine,” I say, before wondering why I’m comforting the person who is trying to comfort me. I hear what sounds like a crying child coming from our building, but if it’s one of her children, my neighbor doesn’t seem concerned.

“Well, um, you see, we hadn’t heard until today, when your mom called.”

“My mom called?”

“She didn’t call me. She called the landlord, and then he called me. I guess your brother listed your mom as a guarantor, and when this month’s rent didn’t show up, the landlord called your brother first. And then he called you, but he said you didn’t pick up, so he called your mom.”

I stop listening, unsure if my neighbor is here because she wants to express her condolences or because the landlord asked her to remind me to pay our rent. That’s when I notice the wailing again. “I’ll mail the check today,” I say.

As soon as I’m heading back up the stairs, I hear her voice behind me saying, “And maybe call your mom? Apparently, she’s worried sick about you.”

When I open the door to our place, the screaming baby sound assaults me along with an acrid smell, and I realize it’s B. She’s shaking and whimpering, and there’s a dark yellow puddle on the far end of the rug. I haven’t left her alone since I got back from the funeral, and I’d forgotten about her separation anxiety.

“I thought you were never coming back,” she says.

“I’m sorry, B,” I say, squatting beside her.

After I clean up the mess, I make out a check to our landlord. I look at the enormous number I’ve just written. This is the largest check I’ve ever written, the first time I’ve ever paid two people’s rents. I won’t be able to do this again next month. Though Mom is technically listed as our guarantor, we only listed her to get a competitive edge in a competitive market, a privilege you and I were both ashamed to have access to but not so ashamed that we didn’t take advantage of it. We asked her to be our guarantor then swore to each other that we’d never ask her or Dad for rent money, no matter what happened.

I need to put in notice at work, but I don’t have the energy to deal with it today. I hardly have the energy to mail the check. And I know I should call Mom to check in, but I still haven’t found my phone, which is a convenient excuse.

“We’re going for a walk,” I tell B as I seal and stamp the envelope. I reach for her leash. She wiggles like a strand of cooked spaghetti.

We set off in search of a mailbox. At every corner, I expect to find a blue box, and at every corner I do not. We’ve just rounded the curved sidewalk that leads up the hill to Buena Vista Park when I finally spot one. I place the envelope in the box and feel a tugging from the end of the leash—B whining and pulling me toward the park.

As we ascend the hill, I catch glimpses of the downtown skyline and the bay. I notice the faraway edges of a lovely scent even through the three layers of my mask. Nobody is around, so I lower my mask and inhale eucalyptus and loam, petrichor, and something that smells like hope. I pull my mask back up, and B and I descend the dirt and wood steps out the other side of the park. Behind a nearby bush, I see a person in a sleeping bag and another person curled atop a winter coat. On the sidewalk, there’s an encampment of eight or nine tents, with a few shopping carts parked alongside. The number of people sleeping outside is astounding, and there are at least twice as many people as there were the last time I left the house.

“This way,” B says, pulling me toward the Haight.

On Haight Street we pass another tent encampment as well as shop windows that are boarded up and the small venue where you performed your last stand-up act. It was a month before you died, and everyone agreed that it was your best work yet. I loved watching you onstage, amazed that this gregarious, charming man was in fact my sensitive and often sullen big brother. How far you’d come from our childhood puppet shows. The marquee at the club reads: Closed until further notice. Wear a mask, San Francisco.

Bialy leads me through Golden Gate Park. We walk and walk and finally pass the Music Concourse, where I see an unfamiliar structure: a Ferris wheel that I’ve never seen before. I wonder if it’s new, or if I’ve simply been sleepwalking through the city these past two years. B pulls me through the park, past ponds and playgrounds, through the roller-skating rink and bison paddock. Just north of the park, I start to worry how we’ll get back if we keep walking. Though she only weighs ten pounds, I’m not sure I have the strength to carry B all the way home. B is determined, quickening her pace and leading me down tree-lined streets and into the Presidio. The trees are taller than I recall, grander, and the park is so large and empty. Suddenly, B perks an ear. There’s a haunting whistling in the wind.

“What is that?” B asks with a growl.

I have no idea, but it sounds like monks chanting. We’re heading north through the Presidio when I make out the towers of the Golden Gate in the distance. Maybe this is why B is sniffing and pulling so hard. I wonder if she can smell you or sense you, if some instinct has kicked in and her tiny animal brain thinks she’ll find you if we go to the place where you took your final step. But I can’t do this. Not today. I crouch down to B’s level and scratch behind her ear and gently tell her we’re going home.

When we finally return to the apartment, B falls asleep in a patch of light in front of your bedroom door. Right after you died, she used to paw at the closed door to your room, as if scratching hard enough would open the door and she’d find you on your bed like you were that last day, when I was in too much of a rush to check on you. I passed your open door and saw you staring at the ceiling, and I should’ve asked what was wrong. Instead of running out the front door to go to the movies, I should’ve invited you to come with me. Better yet, I should’ve canceled my plans, kicked off my sandals, and crawled into your bed, the way you used to crawl into mine when I couldn’t sleep after an episode of Goosebumps.

“Are you okay?” I should have asked.

. . .

Later that night, I open my laptop.

Whooshing sound San Francisco, I type, which returns limited results. Chanting Presidio: nothing. Wind sound north San Francisco spooky turns up a result. I find an article titled, “‘A giant wheezing kazoo’: Golden Gate Bridge starts to ‘sing’ after design fix.” I learn that new railings along the bridge’s bike path are causing a strange sound when the wind passes through them. I laugh. Of course the bridge is to blame for the noise. But God, how you’d love this, that an expensive redesign has resulted in this wacky sound. It’s the kind of thing you’d put into a stand-up routine.

Suddenly I’m descending into a vortex of online information about the Golden Gate Bridge. About the history of its construction. About the protest happening there this weekend. About the dozens of people who die from jumping every year. I watch the video of a man who survived after jumping. I read about a public works project to install netting to save people from this very thing, a project that has been delayed like everything else in 2020.

I try to imagine how impossibly awful you must’ve been feeling. I try to imagine what you were thinking as you leaped from the deck. I wonder if what you were feeling is the same thing Dad felt for so many seasons of our childhood. I wonder if Dad will go the same way as you.

I shut my laptop and rise from the couch. B is still in front of your door. I recall the last time I was in your room—the night I flew home from the funeral. Suddenly, I know where my phone is.

It’s musty in your room, but it still smells like you, like sunscreen and sweat. I flip on the light. B sniffs your rug and jumps onto your bed. Sure enough, my cellphone is facedown on your dresser. When I turn to face B, she’s sitting on your pillow, staring at me.

“He’s really gone, isn’t he?” she says. Her mouth isn’t moving—it’s never moving when she speaks—but I hear her voice. That voice I recognize from some past life.

I nod and sit beside her on the bed. I notice a framed photo on your dresser, one of us as children standing in front of our wooden puppet theater. I remember the scratchy voice you used whenever you played the dog puppet. I remember how the sweet dog character would always reply with the phrase, “Thank you much.”

I tell B that I love her, and when she licks my nose but says nothing, I know I’m no longer going to be hearing your voice and that nothing, and everything, is real. ♦

Rachel Zarrow is a San Francisco–based dog person. Her writing has appeared in Catapult, Electric Literature, Bon Appétit, and the Atlantic. A professional beekeeper by day, she spends the rest of her time walking her dogs, volunteering with Empowerment Avenue (a program for incarcerated writers), and working on a novel.

Karen Chan is an artist and designer living in the Fillmore District. You can often find her lost in thought at a sunny parklet, with a sketchbook in hand. Currently, she is on a quest to try all the delicious pastries that the city has to offer.