How Marilyn Chambers helped define San Francisco’s sexual revolution and became a cultural icon.

On the southeast corner of O’Farrell and Polk Streets in the Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco sits a now-vacant building that once housed, as Hunter S. Thompson noted, “the Carnegie Hall of public sex in America.” When it was opened on July 4, 1969, by brothers Jim and Art Mitchell, the business was considered the premier adult movie palace in San Francisco. Throughout its fifty-year tenure, the Mitchell Brothers’ O’Farrell Theater attracted legions of fans, anti-pornography protesters, degenerates, businessmen, and a revolving door of curious celebrity clients. It was the target of dozens of police raids and a frequent defendant in First Amendment court cases. Operating initially as a movie house, the theater quickly expanded to include striptease and live sex shows. Many adult film actresses got their start dancing at the O’Farrell, including Nina Hartley, C.J. Laing, and Missy Manners. But one young starlet eclipsed all others, becoming synonymous with the Mitchell brothers, San Francisco, and the sexual revolution, and went on to become a superstar of sex: Marilyn Chambers.

For more than four decades, Chambers was an uncommon strain of celebrity. She was internationally famous and had an extraordinarily versatile career in show business spanning films, theater, television, music, and publishing. Her comings and goings were covered in newspaper gossip columns and magazines like any other star. However, she was best known as a porn star, a label she loathed but eventually came to accept.

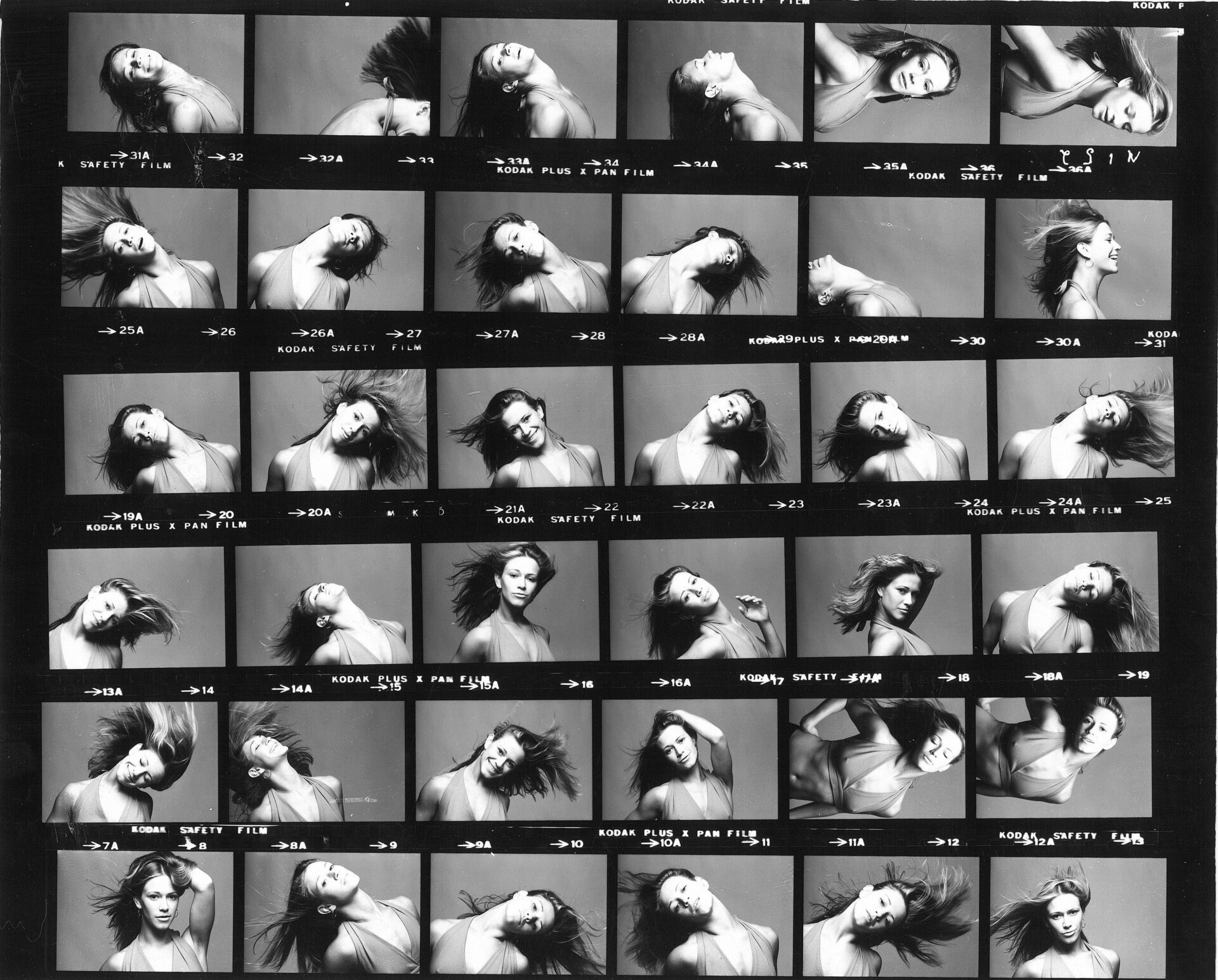

From an early age Chambers knew she wanted to be an actress. Her honey-blond hair framed a face punctuated with striking blue eyes, an elongated nose, and a wide mouth. Her high school class of 1970 awarded her the auspicious honor of “Best Student Body,” a nod to her toned, lean physique earned from years as a competitive swimmer, diver, and gymnast. She bore a strong resemblance to Cybill Shepherd, the modeling industry’s top cover girl of the late 1960s and early 1970s. She hoped that starting out in modeling would lead to show business and acting opportunities, as it had for Shepherd.

After many long months of rejection, Wilhelmina Models, one of the premier agencies in New York, finally spotted something special in Chambers’s look. What they likely noticed in the seventeen-year-old was a wholesomeness, an innocence, a type of purity that sold products. She modeled for the Sears catalog. She did print and television ads for Clairol shampoo and Pepsi. In 1970, executives at Procter & Gamble hand-selected her from hundreds of young women to be the new symbol of young American motherhood on the box of their most successful product: Ivory Snow laundry detergent. The product’s tagline, in use since the late 1800s, was “99 ⁴⁴/₁₀₀% Pure.” Chambers’s image as the fresh-faced girl on the soap box was to be both the key to her success and an ongoing challenge as she attempted to carve out a career in a misogynistic industry that could not accept an openly sexual woman as a serious actress.

. . .

Born Marilyn Briggs in 1952, Chambers grew up the youngest of three children in Westport, Connecticut. She was an entertainer from a young age, putting on shows for her family and starring in school plays. Her mother, Virginia, was a forthright, independent woman who worked as a nurse and often took vacations to Europe by herself without her husband or kids. Marilyn often clashed with her mother and later described their relationship as “oil and water.” Her father, William, was a handsome yet emotionally distant man who worked as a Madison Avenue advertising executive. While in high school, Marilyn would forge her mother’s signature on early-release permission slips and take the train into New York City to do modeling gigs.

Chambers first visited California in 1970, when she was sent by a producer on a promotional tour for the film The Owl and the Pussycat. She had landed a small nonspeaking role in the movie, which starred Barbra Streisand. Still, she thought it strange the producer would send her on any type of press junket when she barely had any screen time, had no lines of dialogue, and was credited under a stage name (“Evelyn Lang”). The producer’s reasons became clear during the tour’s stop in Los Angeles, when he propositioned her in his hotel room. Despite this powerful man’s ability to make or break her career, Chambers, repulsed by her first glimpse of the underside of the movie business, refused his offer. The event prompted her to seek a change of scenery, far from New York and away from seedy Hollywood.

On the press tour, Chambers had visited San Francisco and was immediately taken with the free-spiritedness, openness, and hippie culture of the city. (She considered herself a “hippie chick.”) When the tour was over, she packed up her belongings and drove cross-country to San Francisco. “I believed San Francisco was the entertainment capital of the world,” she said in a 2006 interview.

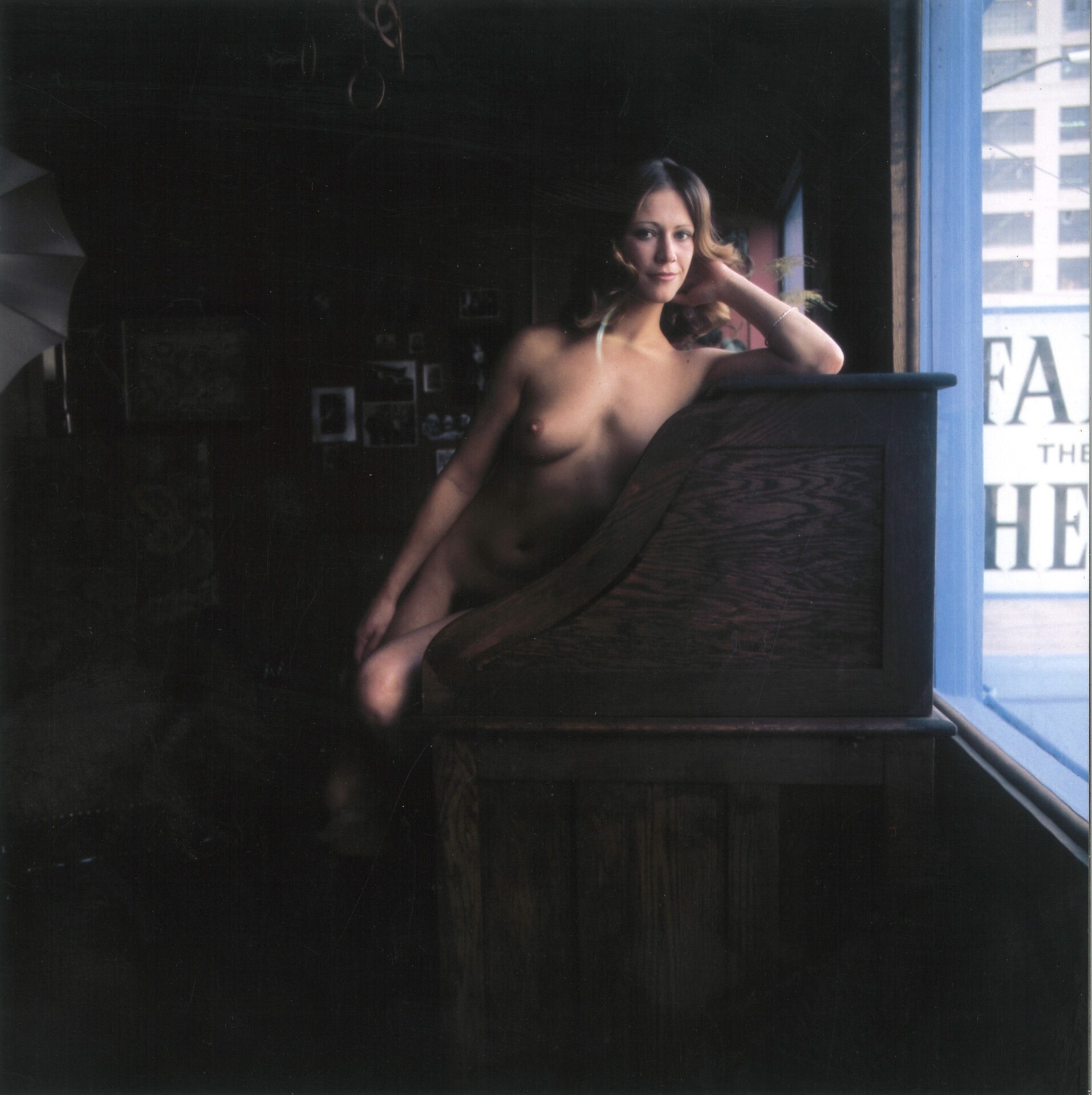

For more than a year, she toiled in the San Francisco arts scene, trying to break into theater and dance groups. To make ends meet, she took odd jobs, including topless and bottomless dancing in small clubs.

In March 1972, a want ad in the San Francisco Chronicle caught her attention: “Now casting for a major motion picture.” She knew this was the opportunity for which she had been waiting. She called the number but was told all the roles had been cast. She begged the woman on the other end to let her audition. “Okay,” the woman said. “But it probably won’t do you any good.”

Modeling portfolio in hand, Chambers made her way to an unmarked warehouse on Tennessee Street, a production facility owned by Jim and Art Mitchell, who produced adult films they showed at their theater on O’Farrell. She felt something was off as soon as she entered the building but dutifully filled out the application handed to her by the woman at the desk. Near the bottom of the application, one question startled her. It read: “Balling or non-balling role?” Surely this had to be a typo, she thought; they must mean “bowling.” She could handle a little bowling, but she wrote down the word “balling.” When she handed back the application, the woman scanned it and asked Marilyn to confirm that she’d be having sex in the film.

“What?! No way!” Chambers said, according to her 1975 autobiography, My Story. “I didn’t know it was one of those films.” Dejected and angry, she started for the door. Art Mitchell spotted her from the second-floor office he shared with his brother. In that moment he knew the beautiful blonde was exactly what they needed for their film. He raced after her and convinced her to come up to the office and speak with them. Self-proclaimed okies from Antioch, the brothers dressed alike and looked so physically similar, with their bald heads, neatly trimmed beards, and wire-framed glasses, that Chambers assumed they were twins. (Jim was, in fact, two years older than his brother.) The Mitchells immediately put her at ease and explained how their operation of making adult films was both legitimate and successful. So successful, in fact, that they had decided to make a full-length hard-core feature film. It was called Behind the Green Door.

. . .

The Mitchell brothers were well known to law enforcement by 1972. The O’Farrell Theater had been raided more than a dozen times since it opened. The films were confiscated, and both patrons and staff were arrested. The brothers were charged with obscenity nearly forty times, and every case was dismissed on the grounds of the First Amendment. Despite San Francisco’s reputation as one of the most liberal cities in America, there were many conservative residents and elected officials who believed the looseness of the era was causing irreparable damage not only to the city but to society on the whole.

Possessing and distributing pornographic material was illegal in most of the country, including San Francisco. But the Mitchell brothers saw a moneymaking opportunity and were savvy enough to know that any controversy generated from their films or their arrests would only serve as extra publicity and add to the allure of their work.

The O’Farrell was the first adult theater owned and operated by the brothers and served as their flagship location. It opened on Independence Day 1969—a conscious decision by the brothers, who firmly believed in First Amendment rights. They would soon open ten more adult theaters throughout California. The O’Farrell was fixed up with hand-sewn drapes, plush carpeting, comfortable seating, ornate chandeliers, and a projection booth. There was even a suggestion box in the lobby. If they were going to operate an X-rated movie theater—and because they knew the police would inevitably raid them—it was going to be classy and attractive. The films were shown on the ground floor, and the brothers’ offices and secondary studio space were on the second floor.

Behind the Green Door was scheduled to be the brothers’ 337th film in just three years—and their first feature-length one. Most hard-core films of the era were called “loops” and ran no longer than about fifteen minutes. The men who participated often wore sunglasses or masks, and the women weren’t exactly models. No one was considered an actor and there were no plots—just sex. Loops were akin to the millions of homemade porn videos found on the Internet today.

Behind the Green Door has a dubious history. Historians and scholars of erotic literature agree it was an underground piece of erotic fiction—sometimes also titled The Abduction of Gloria—that was written anonymously and passed secretively among friends in the form of tattered and stained mimeographed copies. Art Mitchell, who first read the story in college in the early 1960s, claimed it was only about twenty typed pages. The story stuck with him, and by the time he and Jim were ready to make a feature-length film, Art suggested adapting Green Door. (Chambers, for her part, claimed the story was passed around by men in the armed forces while they were in the trenches; every guy who read it would make his own addition to the story.) Since the story was underground erotica, it was difficult to locate a copy. The brothers even went so far as to put an ad in the San Francisco Chronicle that read “$25 and business opportunities for a copy of The Green Door.” They received a few leads but no actual manuscript. Finally, a friend of theirs came through. Her mother in Wisconsin had a copy in a trunk and made a handwritten copy for the brothers.

Chambers liked the idea of the fantasy when the brothers told her the story. A woman named Gloria Saunders is abducted and brought to an elite North Beach sex club where she’s made love to by six women and five men while a diverse group of people watch enthusiastically. Even though it was short on plot, it had more of a story line than nearly any adult film before it. Chambers thought that if she could help make this the sexiest film ever produced, people might take notice. But she worried what her parents would think if they ever found out she was in it, and if her career would ultimately be damaged because she had made a sex film.

To spare herself the decision, she requested compensation so high, she assumed the brothers would never agree to it. She demanded a $5,000 payment plus a percentage of the film’s profits—not the net, the gross. The brothers refused and she went back to her apartment, relieved. An hour later she got a phone call from Jim. The brothers had changed their minds and decided to meet her demands. It all happened so fast. They came over, shoved the contract in front of her, and handed her a pen. She signed her name on the dotted line.

“Had I had the chance to really think about it,” she recalled years later, “I would have said no.” But she was admittedly stubborn and committed herself to the opportunity.

. . .

Behind the Green Door was shot in just thirty days. It opened with great fanfare at the O’Farrell Theater in August 1972. It did swift business and easily broke even. The brothers began producing another feature film, Resurrection of Eve, also starring Chambers. While Eve was in production, Chambers received the second half of her payment for the photos she’d taken for the new Ivory Snow detergent box. It had been two years and she had completely forgotten about it. When she went to the grocery store and wandered down the laundry aisle, there she was on the box, holding a smiling baby. She bought every box the store had and brought one to the brothers’ office the next time she visited.

The brothers knew an extraordinary opportunity had presented itself to them. They were sagacious self-promoters and, knowing they had a bombshell story, wisely waited several months before bringing it to the press. They wanted to ensure Procter & Gamble had distributed enough boxes of the detergent across the country and that a product recall would prove too costly.

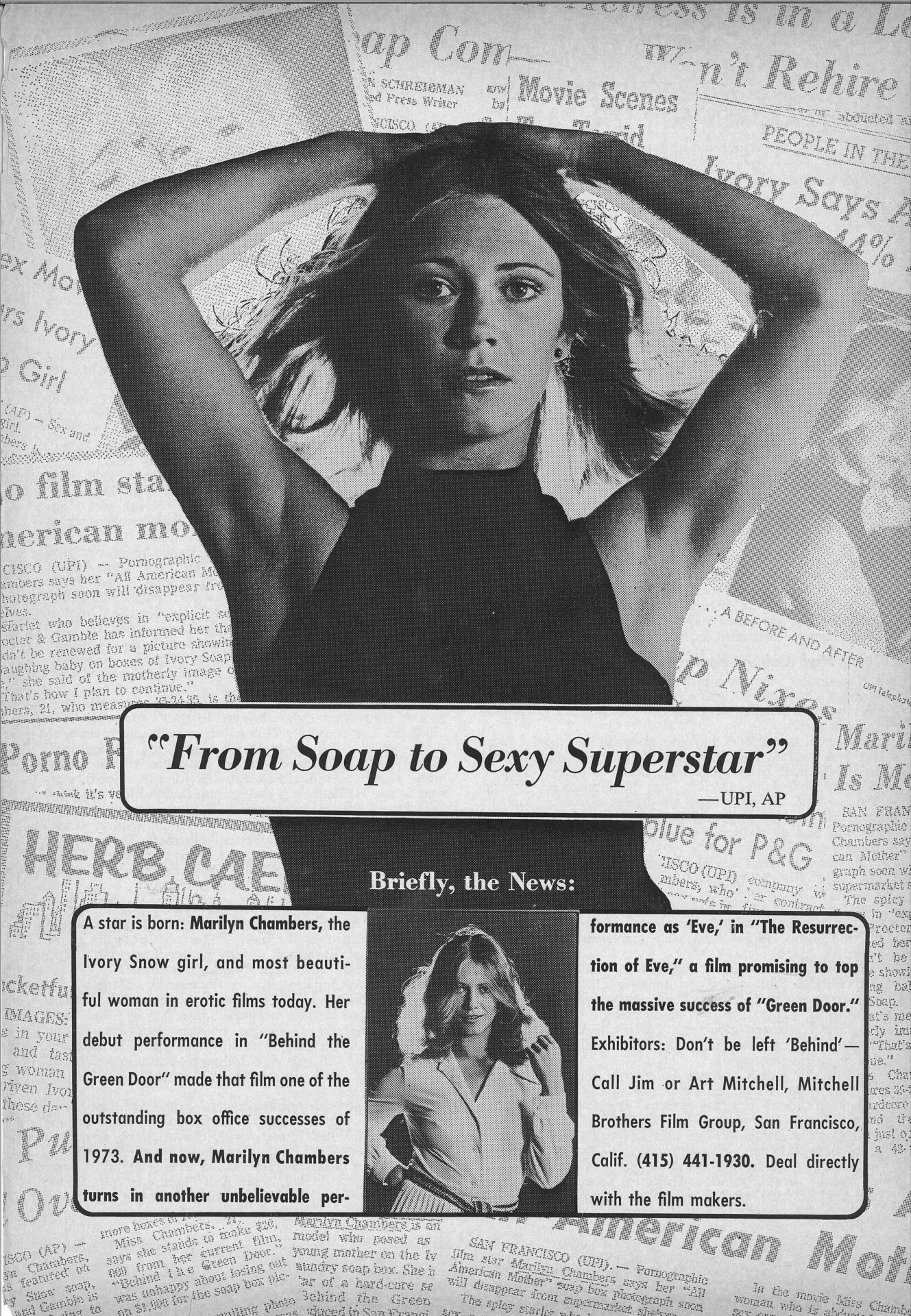

On May 3, 1973, the story exploded. “Mrs. Clean Is a Porno Cutie,” read one headline. Even the staid New York Times ran a short story about it in their “Notes on People” column. The press coverage sent ticket sales skyrocketing, and Green Door earned $60 million in 1973 alone. The film was even feted at the Cannes Film Festival in 1973. It was the first hard-core film to be shown there.

Seeing an adult film became the thing to do. The New York Times even gave the fad a name: “porno chic.” The San Francisco Chronicle featured numerous stories about the controversial trend; famed columnist Herb Caen wrote about it; and local news stations, such as KRON4, covered many press conferences held by the Mitchell brothers and their attorney Michael Kennedy.

It wasn’t just single men who came to see the film. Younger and older couples, and celebrities like Johnny Carson, Jackie Onassis, and Warren Beatty lined up outside theaters. The films were reviewed in trade publications like Variety and The Hollywood Reporter right alongside Disney’s latest features. Linda Williams, film scholar at the University of California, Berkeley, noted in her book Hard Core that the scene in Green Door between Chambers and her Black male costar, Johnnie Keyes, was likely “the first interracial sex scene viewed by a mass mixed-gendered audience.” The film continued to generate revenue during its years-long run in adult theaters across the country, often on a double bill with Resurrection of Eve.

Only one adult film achieved more notoriety and generated more controversy: Deep Throat. That film opened in New York City in June 1972, just two months before Green Door was released. Deep Throat also turned its leading lady into a star. Linda Lovelace graced the cover of Esquire magazine and, like Chambers, she tried to parlay her newfound fame into a career in show business. Lovelace was managed by her husband, Chuck Traynor, whose abusive behavior and polarizing personality had been well publicized.

By 1974, the “porno chic” fad was over. Linda Lovelace faded into obscurity. Chambers parted ways with the Mitchell brothers and took up with Chuck Traynor, who was fifteen years her senior. Together, they created the Marilyn Chambers persona. She would now live like a movie star twenty-four hours a day. She was always to appear glamorous in public, dress in the finest clothes, and take limos to and from events. But there were certain other things Traynor insisted on: that she speak in a low and breathy voice and only speak when spoken to; that she defer to him always, trust his judgment, and never disagree with him; that she stop smoking cigarettes and only partake in alcohol or drugs when he approved; and that she ask permission to go to the bathroom. When she expressed interest in going to community college, he forbade it, noting that her core audience of men would be turned off by a smart woman. He also practiced hypnosis on her. He promised her superstardom and she trusted him completely.

Traynor tried to steer her away from adult films while still capitalizing on her sex goddess image. She performed in a New York cabaret act. She acted in dinner theater in Las Vegas, including Jules Tasca’s The Mind with the Dirty Man—which ran for fifty-two weeks—and Neil Simon’s Last of the Red Hot Lovers. She landed the leading role in David Cronenberg’s horror film Rabid. She starred in an off-Broadway musical revue, Le Bellybutton. She also authored three books, recorded a disco song, and gave perhaps her career-best acting performance in a one-woman stage show called Sex Surrogate, which played in Las Vegas and London.

But for every achievement, there were many more thanks but no thanks. On at least five occasions, by her count, Chambers was cast in Hollywood productions only to be let go a short time after getting the job. She later learned that the producers’ wives were so opposed to someone so notorious starring in their husbands’ films that they insisted the roles be recast. Still, she continued to seek credibility as a serious actress and entertainer and knew she needed a big mainstream hit to help make that happen.

She thought the moment had finally arrived when she heard about the film Hardcore. It was a Hollywood movie about the world of porn films, and the role she wanted was that of a porn star. The film was written and directed by Paul Schrader, who was riding a wave of success as the screenwriter for Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, released in 1976. Hardcore was about a pious businessman whose daughter goes missing on a church trip. A private detective hired to find her discovers she’s been kidnapped and is now starring in pornographic films. Her father, played by George C. Scott, goes on a quest to find her, traipsing through the underbelly of the porn filmmaking world. He befriends Niki, the porn star role Chambers hoped to get, who not only helps him but becomes a surrogate daughter during his search.

Chambers went in to read for the part. After her audition, the casting director told her flat out, “We can’t use you.” She asked why. “Because we’re looking for a porn-star type,” he replied.

Another opportunity lost. Hollywood wouldn’t cast her in roles because she was a porn star, but when she auditioned for the role of a porn star, she was considered too wholesome to be one. That was the paradox of being Marilyn Chambers. A lucky break had catapulted her to stardom. Then, by creating the persona of Marilyn Chambers—a glamorous, twenty-four-hours-a-day sex queen and all-around entertainer—she maintained a level of fame and success few other women in the adult industry have achieved. But for Chambers, porn was a means to an end; she wanted to be a serious actress.

With no other options, Chambers returned to adult films in a big way. Insatiable, from 1980, was a major box- office success and is considered a classic of its genre. Released at the dawn of the home video boom, Insatiable was the biggest-selling home video of any genre for two years in a row. A couple of other X-rated feature films followed, and even an R-rated action comedy, Angel of H.E.A.T. She was also given her own dramatic television series that aired on the Playboy Channel in the early ’80s. But despite being the channel’s highest-rated show and a fan favorite, it ran for only one season. It seemed no matter how hard Chambers tried to make it in Hollywood, all roads led back to adult films. By the mid-1980s, she was ready to retire.

. . .

Throughout her career, Chambers frequently returned to San Francisco and the Bay Area—whether to promote a project, film a movie, make personal appearances, or perform at the O’Farrell Theater.

One particular performance in 1985 made national headlines. San Francisco’s then-mayor, Dianne Feinstein, never a fan of the Mitchell brothers, wanted to crack down on adult theaters in the city. What better way to draw attention to the issue than to arrest the country’s most famous porn star at the city’s premier adult establishment? A sting operation was ordered and Chambers was arrested during her performance and carried out of the theater nude by several San Francisco police officers. She was booked on charges of soliciting prostitution, but the charges were later dropped. In fact, the night of the arrest, many of the police officers lined up to have their photos taken with Chambers in her jail cell.

Feinstein’s plan backfired. Locals were more angered by the sting operation and Chambers’s arrest than the idea of too many adult theaters operating in the city. When Chronicle columnist Warren Hinckle wrote a piece criticizing the San Francisco Police Department for the arrest, he was arrested the next day for walking his dog without a leash. This angered the public even more. The Mitchell brothers, never ones to pass up free publicity, posted Mayor Feinstein’s unlisted phone number on the theater’s marquee along with the words “For a good time, call Dianne.”

By the mid-1980s, Chambers’s life was spiraling. She was addicted to cocaine and alcohol, had divorced Traynor, and had begun dating her bodyguard, Bobby D’Apice, a pairing mired in constant physical and emotional abuse. Over the next several years, Chambers fought to get sober and leave her abusive relationship. By the time she turned forty in 1992, she was clean and had remarried. She also became a mother, which she considered her greatest achievement.

As the new millennium approached, the O’Farrell Theater remained a go-to spot for tourists seeking a seedier side of San Francisco, but it had lost its edge. The Internet was fast replacing live sex shows as a source of adult entertainment, just as home videos had begun replacing adult movie theaters in the 1980s. Long gone were many of the regular employees and entertainers Chambers had known throughout the years. One person’s absence in particular cast a pall over the entire establishment: Art Mitchell. In 1991, Art was fatally shot in his home by his brother Jim. Jim was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter and sentenced to six years in San Quentin. He was released in 1997 and ran operations at the O’Farrell Theater until he passed away in 2007.

Chambers gave a farewell performance at the O’Farrell Theater in July 1999. Her return made headlines; San Francisco hadn’t forgotten its Ivory Snow girl. Indeed, Mayor Willie Brown declared July 28, 1999, “Marilyn Chambers Day” in the city and county of San Francisco and praised her artistic presence, vision, and energy.

Ten years later Marilyn Chambers was dead. She had a cerebral hemorrhage and an aneurysm related to heart disease, and died ten days shy of her fifty-seventh birthday. Industry performers old and new remembered her warmly. Many of her childhood friends were devastated and spoke highly of Chambers the person, as opposed to Chambers the persona. For many baby boomers, a pivotal figure of their own burgeoning sexuality had passed. Behind the Green Door, Resurrection of Eve, and Insatiable were the first adult films seen by a generation.

. . .

It would be easy to cast Chambers aside as another victim of the porn industry. People love to believe the industry guarantees an almost certain early death, especially for women. But that’s a cop-out. Chambers never denigrated the industry that made her famous. “For me to be put on a pedestal and adored by millions of men, I loved that,” Chambers said in an interview with John Hubner printed in Hubner’s 1993 book, Bottom Feeders. “I never felt exploited by Chuck or anybody else. I exploited me. Hollywood’s concept of sex is so corrupt. They still think sex is dirty. They’re afraid of it. They were afraid to show people that a porn star was smart and had talent and could act. That works against what society thinks.”

A series of remarkable circumstances had turned Chambers into an instant celebrity. This happens all too frequently today. But it takes guts, perseverance and, above all, talent, to sustain a four-decade career.

Life as an entertainer comes in many forms, and despite Americans’ puritanical views toward sex, few women in show business before or since have achieved Marilyn Chambers’s level of fame and success. She’s woven into the fabric of American pop culture as both a symbol of and an avatar for the sexual revolution. She transformed an industry and forced important conversations about sexuality that continue today. Her contributions should be reconsidered, and her life as a woman in show business is one that still resonates.

“The reason I made it is because of the road I took,” Chambers recalled in a 1989 appearance on Live with Regis and Kathie Lee. “You know, I believe in fate. I must say that when I was doing X-rated films, I had a great time. And I don’t regret a thing.” ♦

Jared Stearns is a San Francisco–based writer working on a biography of Marilyn Chambers. He’s lived in the same Tenderloin apartment for more than sixteen years. It’s rent controlled so he can never leave.