Behind the scenes at the Cable Car Museum.

The Cable Car Museum is a free museum located at the corner of Mason and Washington Streets in San Francisco’s Nob Hill. The building, also referred to as the Cable Car Barn, was originally built in 1887, rebuilt after the 1906 earthquake and fire, and then refurbished in 1967 to showcase the “heart and soul” of the cable car system. It includes the historical and technical exhibits about cable cars that inspired this piece.

HOW DO CABLE CARS WORK? Cable cars function by use of a “grip.” Like a giant pair of pliers, the grip reaches into the channel beneath the tracks and clamps onto the moving cable so that the car is pulled along for the ride. The tightness of the grip determines the speed of the cable. A tight grip translates to a cable car moving at the full speed of the cable (9.5 miles per hour), whereas a looser grip means a slower-moving car. The gripman controls the cable car by pulling the lever of the grip backward to accelerate the car and pushing it forward to release the cable and slow down. Today’s gripmen still operate the cable car in the same way as they did in the early 1900s.

HOW DO CABLE CARS STOP? Releasing the cable makes the cable car slow down, but like regular cars, cable cars also have brakes. The four 24-inch-long track brakes made of pinewood are activated by a hand lever next to the grip. Because of the friction of the wood against the metal tracks, passengers can sometimes smell burning pine when cable cars brake. The pinewood brakes grip the track tightly, meaning the cable cars can stop quickly, but they need to be replaced every two to four days, as the friction wears down the wood.

DO THE CABLES WEAR OUT? Due to the constant stress on the cable from gripping, ungripping, and passing through the hundreds of underground pulleys, the cables do get damaged. Although they almost never break all the way through, individual wires and strands do break off. When this happens, the cable must be stopped and replaced. The old cable is cut and a new cable is tied to it and run through the powerhouse at half speed. Once the new cable makes it back to the powerhouse, the “splicers” (the mechanics who do the wire rope maintenance) begin the painstaking process of replacing and splicing the cable together, which takes about five hours. In general, cables last between 75 and 250 days.

HOW MANY CABLE CARS ARE THERE? There are a total of 40 cable cars, but only 27 are ever running at a given time. There are 28 Powell Street cars and 12 California Street cars. When the cars aren’t on the clock, they take the track from Washington Street up to the top floor of the building, where they are stored and repaired.

WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A POWELL STREET CAR AND A CALIFORNIA STREET CAR? The Powell Street cars are single-ended and require turntables at the end of the line to turn the cable cars around. The California Street cars are double-ended and have a set of control levers on both sides. In order to switch directions, the double-ended car simply crosses over to the opposing track and the gripman switches sides.

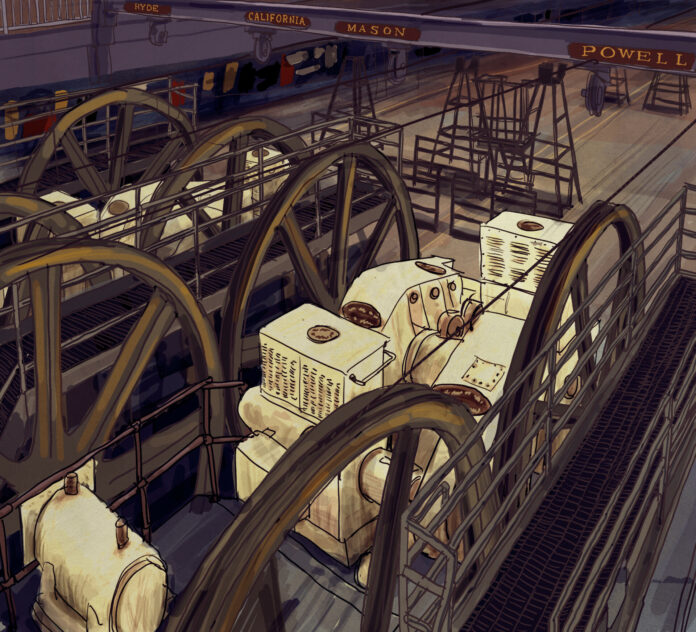

WHY IS THE MUSEUM ALSO CALLED THE POWERHOUSE? All four cable routes (California, Powell, Hyde, and Mason) begin at the Cable Car Museum. The powerhouse of these four cable systems, which consists of large electric motors, gears, and pulleys (also called “sheaves”), can be seen from the viewing deck within the museum. Each of the four motors has 510 horsepower, which translates to cables moving at 9.5 miles per hour all day long. From the museum’s sheave room downstairs, it’s possible to see the cables moving underground at the intersection of Mason and Washington Streets.

IS IT TRUE THAT THE CABLE CARS WERE ALMOST VOTED OUT OF EXISTENCE? Yes. In 1947, then-Mayor Roger Lapham tried to replace cable cars with electric buses, which were twice as efficient. Luckily, concerned citizen Friedel Klussmann founded the Citizens’ Committee to Save the Cable Cars and rallied enough support to pass Measure 10, which ordered that San Francisco maintain the Powell Street cable cars. If not for Klussmann’s intervention, we might not have any cable cars today. The cable car system was later declared a National Historical Landmark in 1964, which cemented the survival of the cable car. Dedicated in 1997, the Friedel Klussmann Memorial Turnaround at Fisherman’s Wharf honors her efforts. ♦

Amanda Legge is cofounder and creative director of The San Franciscan. She grew up in the Bay Area and works in fintech. Outside of work, the only hobby she has is this magazine.

Dan Bransfield is an author, illustrator, and animator living in Presidio Heights. He created The Word Cage for therumpus.net and is a contributor to Edible San Francisco magazine. He enjoys sunny days in the city’s various parks, tennis, and hangouts at Breck’s café.