San Francisco’s Psychedelic Zeitgeist.

“The ballrooms were like a big announcement and front door…into The Life.” – Tom Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test

Listen to the curated playlist that accompanies this piece to hear a selection of live and studio recordings from the height of San Francisco’s rock ballroom era.

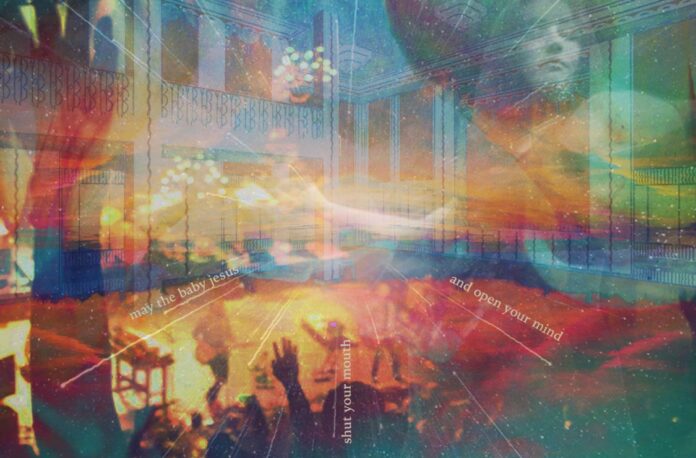

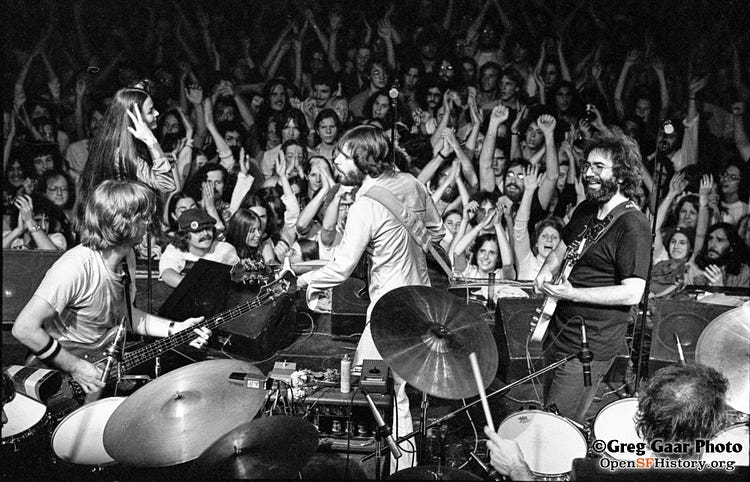

A show at one of San Francisco’s famed rock ballrooms was more than just a concert. It was a complete sensory experience: layers of electric guitars trading licks over splashy drums, pulsating projections moving across the walls in sync with the music, the smell of incense and hash hanging over a sea of heads. At the Fillmore, the customary barrel of Red Delicious apples at the front door — often handed out by promoter Bill Graham himself — even gave the experience its own taste, a delight undoubtedly enhanced by those who prefaced it with one mind-altering drug or another.

A mile away, a similar atmosphere pervaded the Avalon Ballroom. Overseen by Chet Helms, Bill Graham’s polar opposite in almost every way, shows at the Avalon were a cozier affair but a production all their own. Band and audience members alike dressed in a potpourri of digs: flowing scarves, embroidered jackets, beaded headbands, or sometimes nothing at all. Their silhouettes swayed and danced beneath the chandeliers, with liquid light shows projected onto bedsheets hung from the balcony.

Originally intended for dance socials in the 1910s, the ornate ballrooms lent themselves graciously to the new generation who gathered there. Stepping inside, Grace Slick recalled in her memoir, “you have the feeling you’ve just entered seven centuries all thrown together in one room…. Disco balls and medieval flutes. Day-Glo space colors and Botticelli sprites. The howl of an amplifier and the tinkling of ankle bracelets.”

The ballrooms provided a backdrop for the budding San Francisco Sound, housing “dance concerts” headlined by bands like Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, and Big Brother and the Holding Company. The music, with its free-flowing guitar interludes and acid-infused lyrics, sounded best in a live setting, feeding off the energy from the audience. While smaller venues had suited the intimate beatnik and folk performances of the first half of the ’60s, the new era demanded spaces large enough for a celebration.

“Nowhere else in the country has a whole community of rock music developed to the degree it has here,” music critic Ralph Gleason wrote in the San Francisco Chronicle on March 19, 1967. “At dances at the Fillmore and the Avalon…thousands upon thousands of people support several dozen rock ’n’ roll bands that play all over the area for dancing each week. Nothing like it has occurred since the heyday of Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey. It is a new dancing age.”

. . .

The two halls were built within a year of each other, from 1911 to 1912, just as ballroom dancing was beginning to hit its stride on the West Coast. At the corner of Fillmore and Geary, in the upper stories of an Italianate brick building, the Majestic Academy of Dancing opened for business. Less than a mile away, at 1268 Sutter, the stately hall that would become the Avalon opened as the Puckett Academy of Dance, described in a 1923 Chronicle article as “one of San Francisco’s best-known academies of the [ballroom] dance.” Here, experts would come to teach the latest steps from around the world, preparing students to impress at their next high-society engagement.

With sprung wood dance floors, gilded columns, and sparkling chandeliers, the San Francisco ballrooms had been an opulent setting for social affairs in the early twentieth century. And when swing dancing took the nation by storm in the 1930s, the halls welcomed the change, their walls reverberating with the music of Benny Goodman and Count Basie as dances spilled into early morning.

After the lull of the war years, live music returned in yet another form. Local entrepreneur Charles Sullivan took over the lease at the Fillmore-and-Geary hall in 1952, changing the name to the Fillmore Auditorium and opening the previously whites-only venue to its predominantly Black neighbors. Building upon the Fillmore’s new reputation as the Harlem of the West, Sullivan established a business that booked popular Black artists like James Brown, the Temptations, and Ike and Tina Turner. He transformed the Fillmore into a highly successful concert venue.

In 1965, citing aging buildings and claims of “moral decay,” the city deemed the Western Addition neighborhood blighted and carried out a sweeping redevelopment plan that demolished hundreds of Black-owned businesses and pushed an estimated 10,000 people out of their homes. At the same time Charles Sullivan was struggling to keep his venue out of the bulldozers’ path, the counterculture movement was starting to seep out of the Haight-Ashbury district. Out of this movement came two rival concert promoters poised to usher the ballrooms into a new era.

. . .

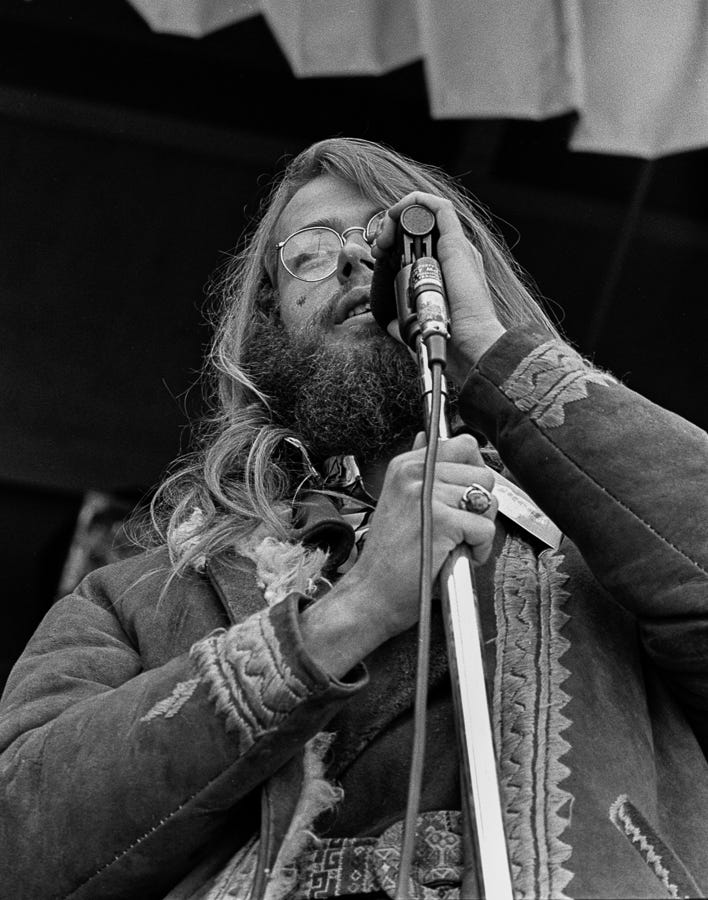

Chet Helms could have easily been mistaken for a member of one of the many bands he worked with. With long hair and wire-frame spectacles, the Texan–turned–San Franciscan was a familiar face in the Haight organizing informal jam sessions and presenting “dance concerts” as part of the Family Dog, a local hippie cooperative. With no formal experience, Helms took on the role of unofficial manager and booking agent for Big Brother and the Holding Company, a San Francisco band whose popularity skyrocketed after Helms suggested a new singer: his old friend Janis Joplin. Helms was, according to Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart, the “heart and soul” of the San Francisco counterculture community, always gravitating toward its artistic center.

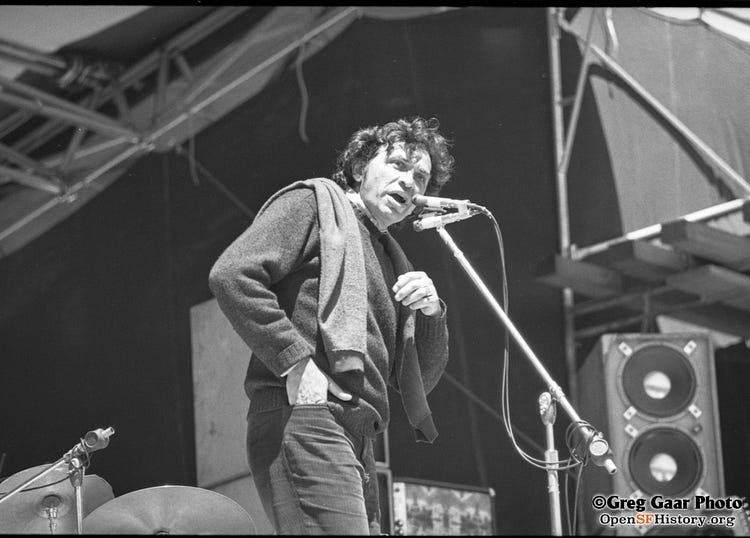

Bill Graham, on the other hand, had been on the scene for less than a year by 1965 and already had a reputation for being unrelenting, uncompromising, and undeniably astute. Born in Germany and shuffled from place to place as an orphan during World War II, he landed in the City after a string of odd jobs in New York and LA. As self-appointed manager for the San Francisco Mime Troupe, he found his calling when troupe leader R.G. “Ronnie” Davis was arrested for performing without a permit at Lafayette Park. Graham jumped into action, organizing a benefit event to pay for the legal fees. Fueled by his sharp promotional skills, the benefit — held in a loft on Howard Street and featuring an impressive lineup of artists, poets, and musicians — was a great success. Seeing an opportunity, he set about organizing another.

The second Mime Troupe benefit was to be held at the Fillmore Auditorium on a sublease from Charles Sullivan. Introduced to each other by Family Dog member John Carpenter, Bill Graham and Chet Helms struck up a deal: Graham would put down the money for the show, Helms and Family Dog Productions would provide the bands. The show was a hit, featuring local groups the Great Society, Quicksilver Messenger Service, and the Grateful Dead, along with the Chicago-based Butterfield Blues Band.

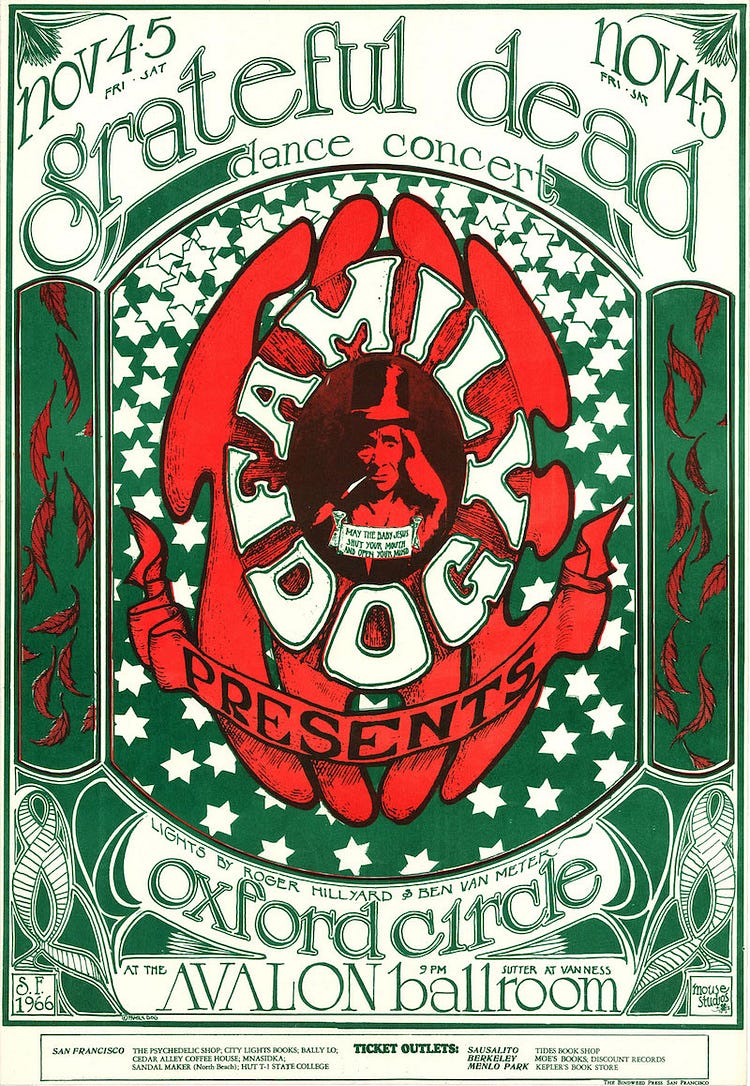

It seemed like a perfect match: Graham had the business smarts, Helms had the connections. And for a while, the two collaborated on organizing rock concerts during the Fillmore’s off nights while Charles Sullivan continued to book a dwindling number of R&B shows. But it was Graham’s relentless ambition that eventually got him contracts with big-name bands and the full lease to the Fillmore, without the go-ahead from Helms. Calling Graham’s dealings a “breach of honor,” Helms broke off from Graham and took over the former dance hall at 1268 Sutter, christening it the Avalon Ballroom.

. . .

From April 1966 to November 1968, the Avalon came alive nightly with psychedelic projections and the Family Dog’s ever-growing rotation of San Francisco rock bands. From the stage up to the balcony, the old ballroom proved to have exceptional acoustics and, in Helms’s view, a superior dance floor. “When seven or eight hundred people got dancing,” he recalled to journalist Robert Greenfield, “the floor moved in sync. It helped you.” It’s where the Grateful Dead’s early live albums Vintage Dead and Historic Dead were recorded, and where — as feelings of peace and love radiated out of the Haight-Ashbury — a harmonious gathering of rock musicians, hippies, Hells Angels, and Krishna Consciousness leaders gathered for the 1967 Mantra-Rock Dance. As the Vietnam War escalated and the chasm between generations widened, the youth of the Bay Area carved out their own community under Chet Helms’s guiding hand, finding sanctuary among the music and red flocked wallpaper.

Meanwhile, at the Fillmore, music history was being made on an even grander scale. Graham’s keen insight and dogged determination produced musical pairings that would never have shared a bill otherwise: B.B. King and Moby Grape, Gábor Szabó and Jimi Hendrix, the Mothers of Invention and Lenny Bruce. He pulled in some of the biggest stars of the day — Otis Redding, The Byrds, The Who — while holding weekly auditions for up-and-comers, which led to both Carlos Santana and Tower of Power having their first public gigs. “Bill had an educational mission. He brought us artists we’d never seen or heard before,” said poet Steve Surryhne, who was a student at San Francisco State University at the time. “It felt like the center of the musical universe.”

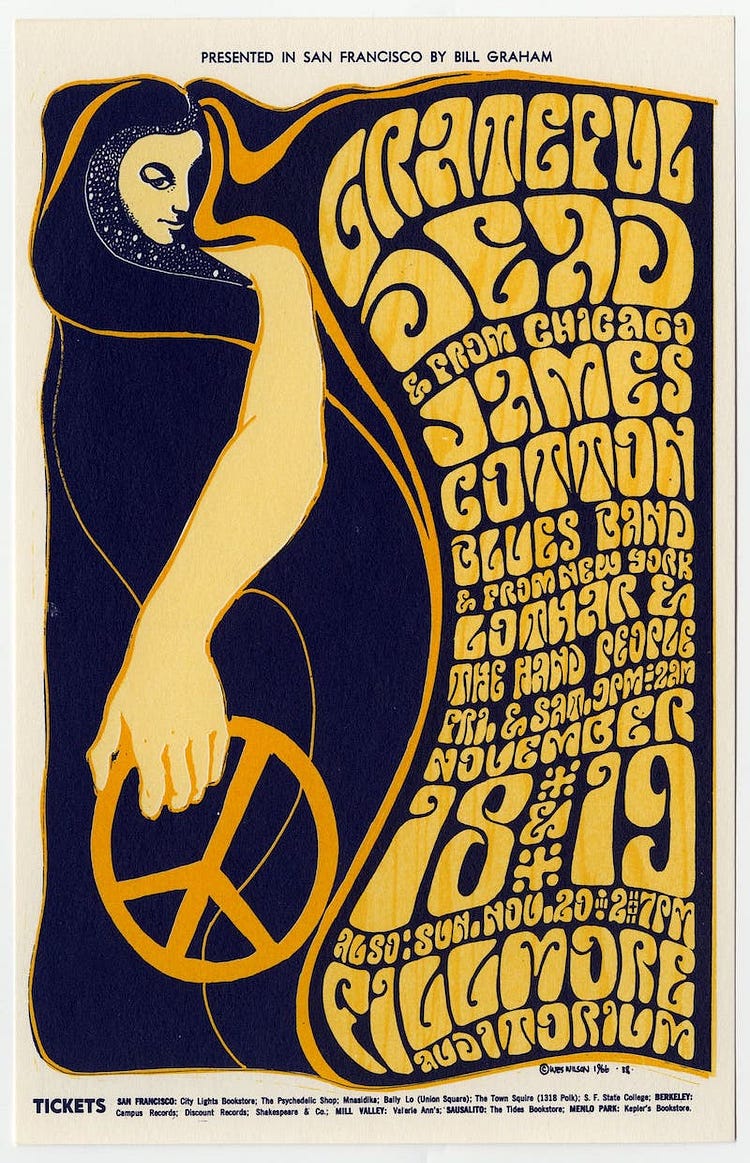

Graham contracted artist Wes Wilson to create the posters for each weekend’s shows, upping the budget so the Fillmore could have color prints instead of black-and-white. Wilson’s ballooning, kaleidoscopic lettering and electrifying graphics adorned head shops around the city alongside the artwork of Stanley Mouse and Alton Kelley, who produced equally trippy posters for the Avalon. “Each party would try to outdo the other,” Wilson told Robert Greenfield. “It created a great deal of positive energy in the field.”

And while Helms and Graham may have butted heads, they knew their success relied on the sharing of their artists and audiences. Luckily, the abundance of local bands made it easy for the promoters to keep both venues filled Thursday through Sunday of every week. In Jerry Garcia’s words, the Avalon was “a good old party” and the Fillmore was “the thrill of opening night.” Those who wanted to experience both could, and for a cover charge of just three dollars each. Big Brother and the Holding Company would pay tribute to the scene in “Combination of the Two,” the opening track on their 1968 album Cheap Thrills. “It’s about the Avalon and the Fillmore,” guitarist Sam Andrew told biographer Ellis Amburn. “Chet is the spiritual side of life and Graham is the aggressive, hard, money side…. You need both those things in life, the combination of the two.”

. . .

By 1968, Bill Graham had developed a successful formula. He’d launched the Fillmore East in New York, and had enough leverage to open two new rock ballrooms in San Francisco: the Fillmore West (previously the Carousel Ballroom) at Van Ness and Market, and the expansive Winterland Ballroom, a former ice-skating rink and auditorium at 2000 Post Street. In 1969, the original Fillmore was handed over to new operators — local band Flamin’ Groovies and their manager, Al Kramer — who called it The New Old Fillmore. The Groovies kept the lights on for two more years, promoting local and touring bands alike, until shuttering the space at the end of 1970. It would remain closed to the public for a decade.

Meanwhile, Chet Helms had drifted in the opposite direction. With less funding and a habit of letting friends — and friends of friends — into his shows for free, Helms was running out of money. Unable to afford to renew his lease, he decided to relocate. Family Dog Productions took up residence at the sand-speckled Ocean Beach Pavilion from 1969 to 1970. Short-lived but spectacular, the venue occasionally advertised as “the Family Dog on the Great Highway at the edge of the Western World” and regularly hosted the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, and Country Joe and the Fish.

Yet with the closing of the Avalon and the original Fillmore, an irretrievable piece of the San Francisco Sound went too. In 1968, Ralph Gleason noted that the “new dancing age” he’d written about just a year prior had started to fade away as the bands became more complex and the concerts more calculated. “The Fillmore [West] and Winterland presentations are star-system shows,” Gleason wrote of Graham’s latest productions, “[making] the audience into spectators rather than participants.” He drew a parallel from the swing era, “in which the original jitterbugs became the Sinatra Swooners and then the concert audience crowding around the bandstand.”

Like many of the artists who graced their stages — Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin — the rock ballrooms of San Francisco had hit an extraordinary high before their flames were extinguished. By 1971, Chet Helms’s Family Dog Productions had gone bankrupt, and Bill Graham was busy running a record label and organizing large-scale outdoor concerts. As the sole relic from the 1960s rock ballroom era, Winterland continued to attract big names in the following decade, achieving immortality as the setting for the Martin Scorsese-directed The Last Waltz, the documentary capturing The Band’s last concert. In 1978 Graham finally pulled the plug, putting together one last concert — a New Year’s Eve show headlined by the Grateful Dead that lasted until dawn — before permanently closing its doors.

Winterland sat empty for seven years before it was demolished and replaced with apartments. The Fillmore West at Van Ness and Market became, unceremoniously, a Honda car dealership. The Avalon met a slightly more dignified fate, operating as a movie theater for many years and briefly reopening as a music venue from 2003 to 2005. The building has since been converted to office space. Perhaps bolstered by its long history in the neighborhood, the Fillmore was the only venue that managed to make a comeback: after operating as a private neighborhood club in the 1970s and a punk rock hangout in the 1980s, it reopened again as the Fillmore in 1994. In keeping with Graham’s tradition, the barrel of apples was reinstated at the top of the steps and the same message offered to entrants: “Have one, or two.”

San Francisco has had no shortage of storied musical eras, from the Harlem of the West to the height of the punk scene to the proliferation of electronic music and rave culture. But the city never quite forgot those few enduring years when Bill Graham, Chet Helms, and the rock bands of San Francisco held the reins. Together with the light show artists, graphic artists, and an entire generation of flower children, they built a fleeting utopia, music and magic caught in those magnificent halls like lightning in a bottle. ♦

Nikki Collister hails from Southern California but considers herself a San Franciscan at heart. She graduated with a degree in ethnomusicology and works as a product manager in the travel industry. In her spare time, she enjoys blogging about classic rock and running an Instagram account for her cat, Special Agent Dale Cooper.

Danielle Calibird Fernandez is a Bay Area native. A joyful spirit and love of Mother Earth informs her artistry. She works in the veterinary world but also started DragonSpunk, a nonprofit focused on gardening and habitat restoration. In the recent past, she attended Parsons School of Fashion and was a teacher in NYC.